We know that plants can inspire art. If you, personally, still require convincing on that point, just have a look at Elizabeth Twining’s Illustrations of the Natural Orders of Plants, the drawings of Ernst Heinrich Haeckel, Elizabeth Blackwell’s A Curious Herbal, and Nancy Anne Kingsbury Wollstonecraft’s Specimens of the Plants and Fruits of the Island of Cuba — not to mention the paintings of Georgia O’ Keeffe — all previously featured here on Open Culture. But those works concern themselves only with plant life as it exists above ground.

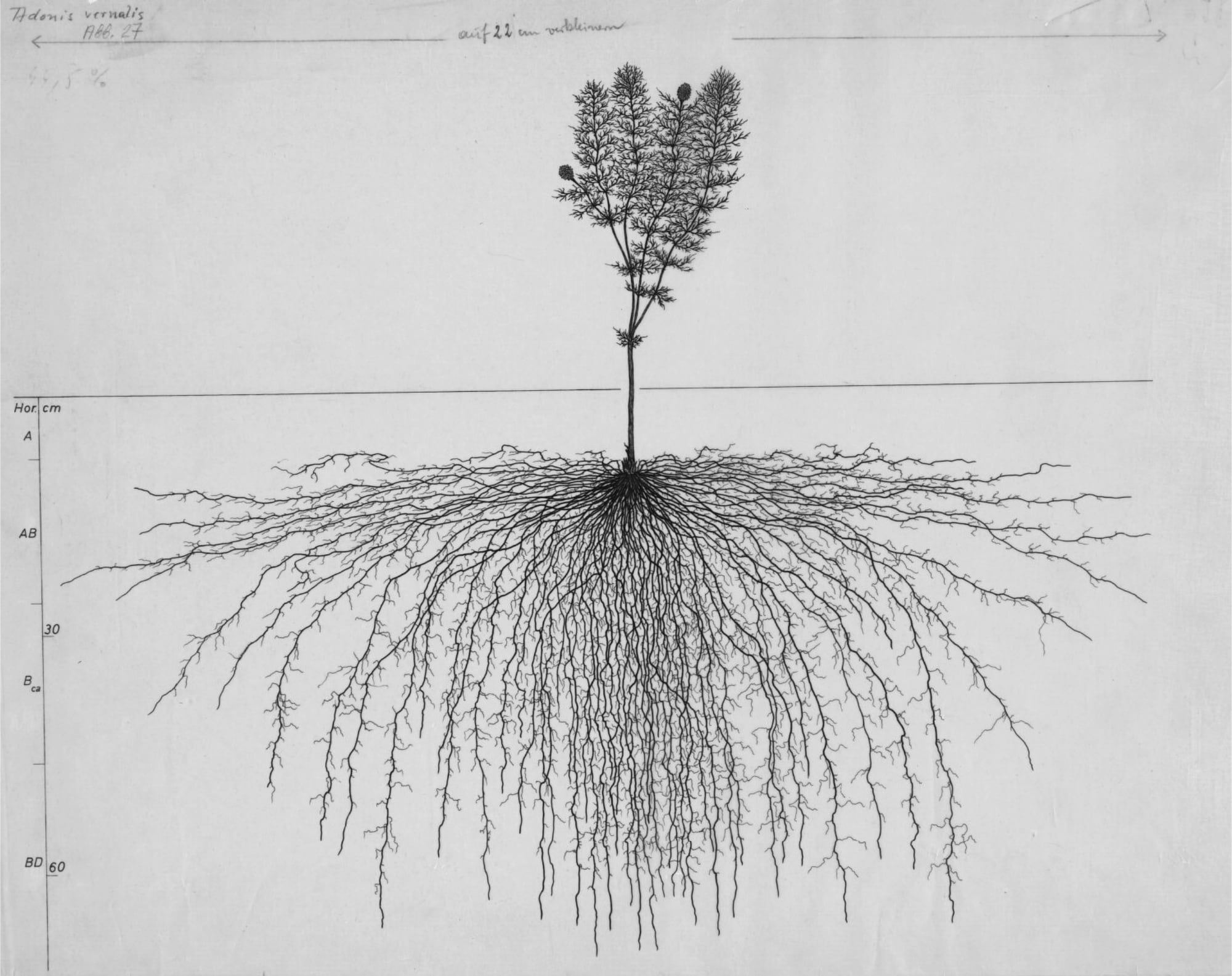

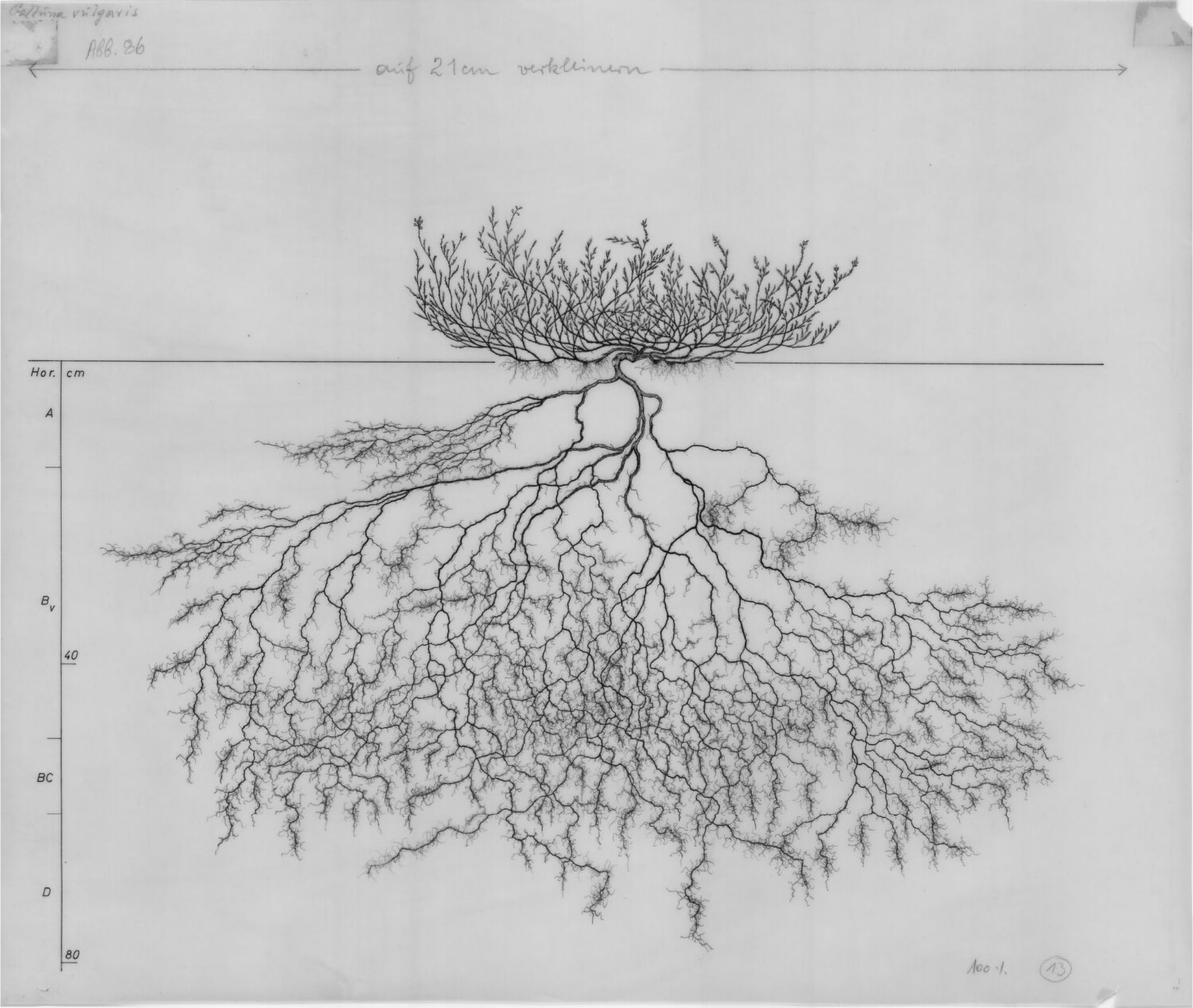

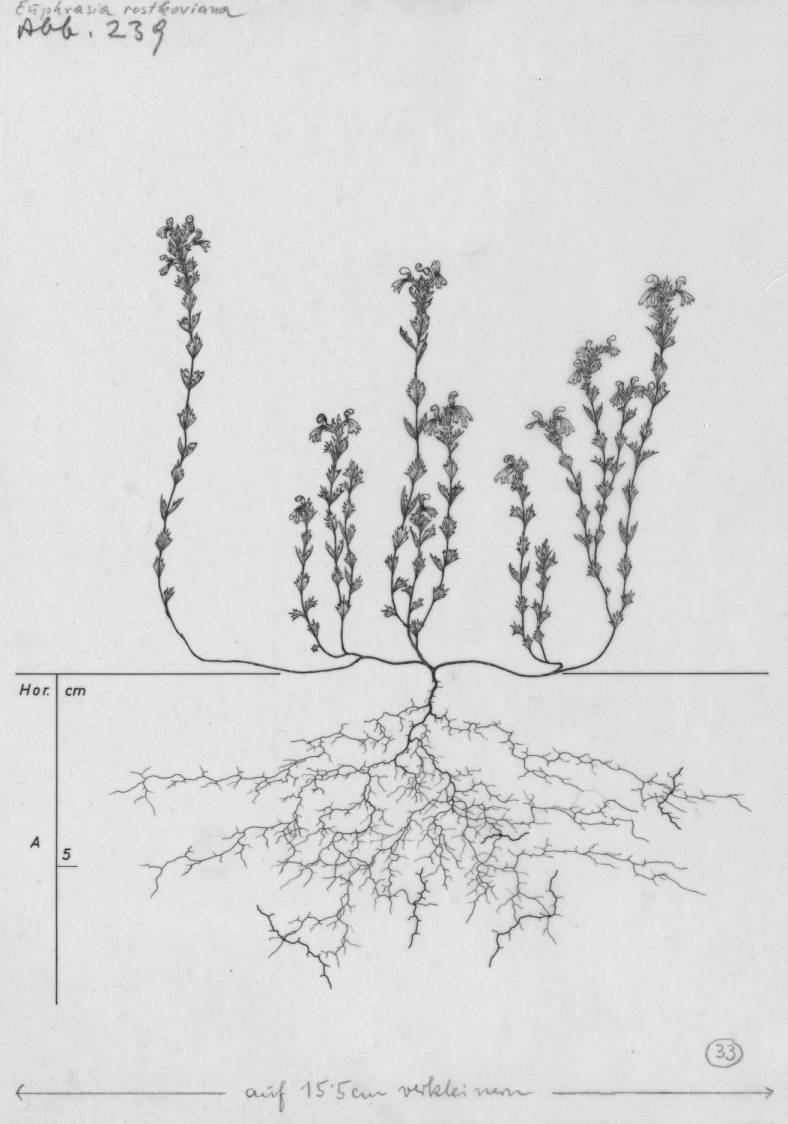

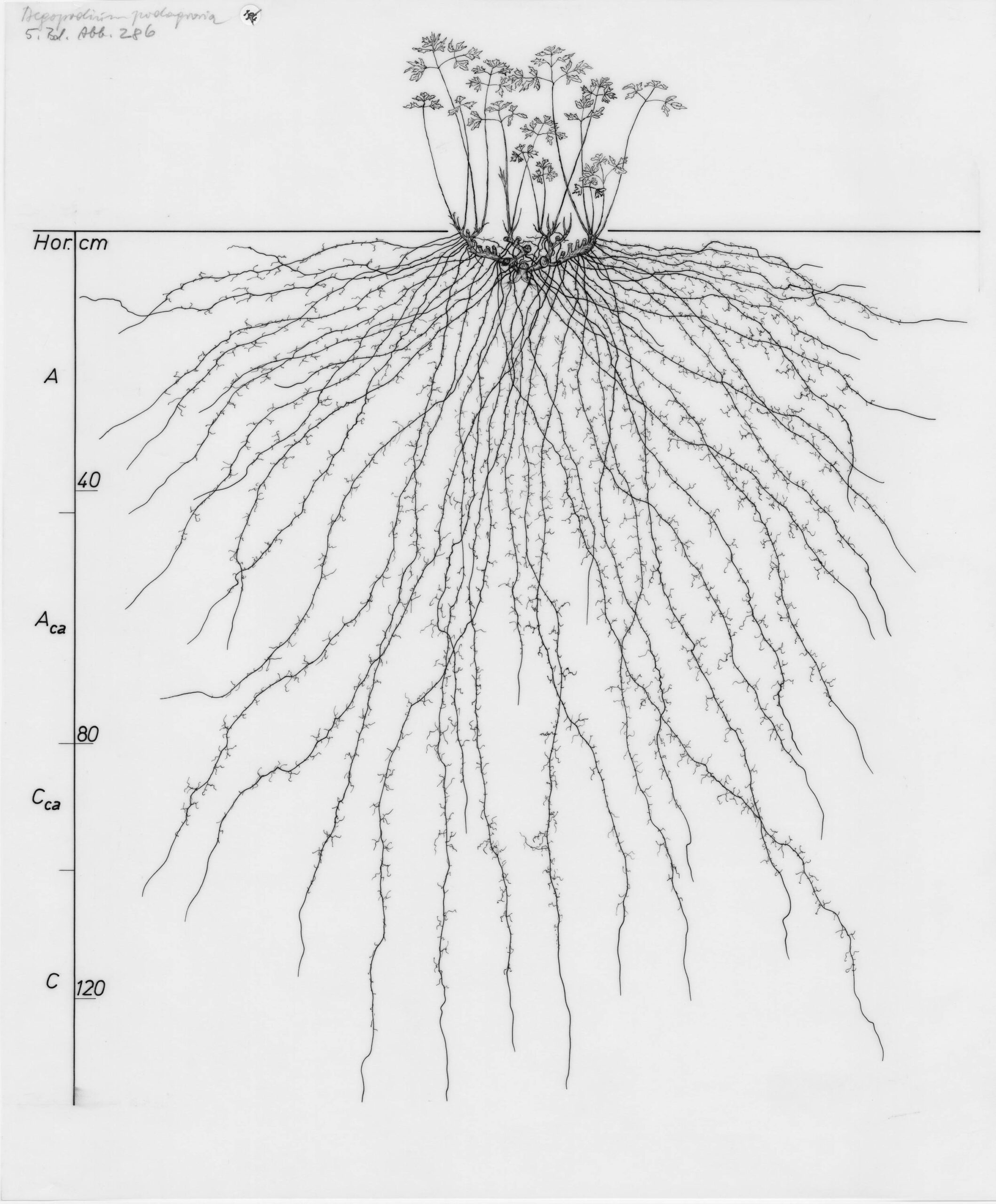

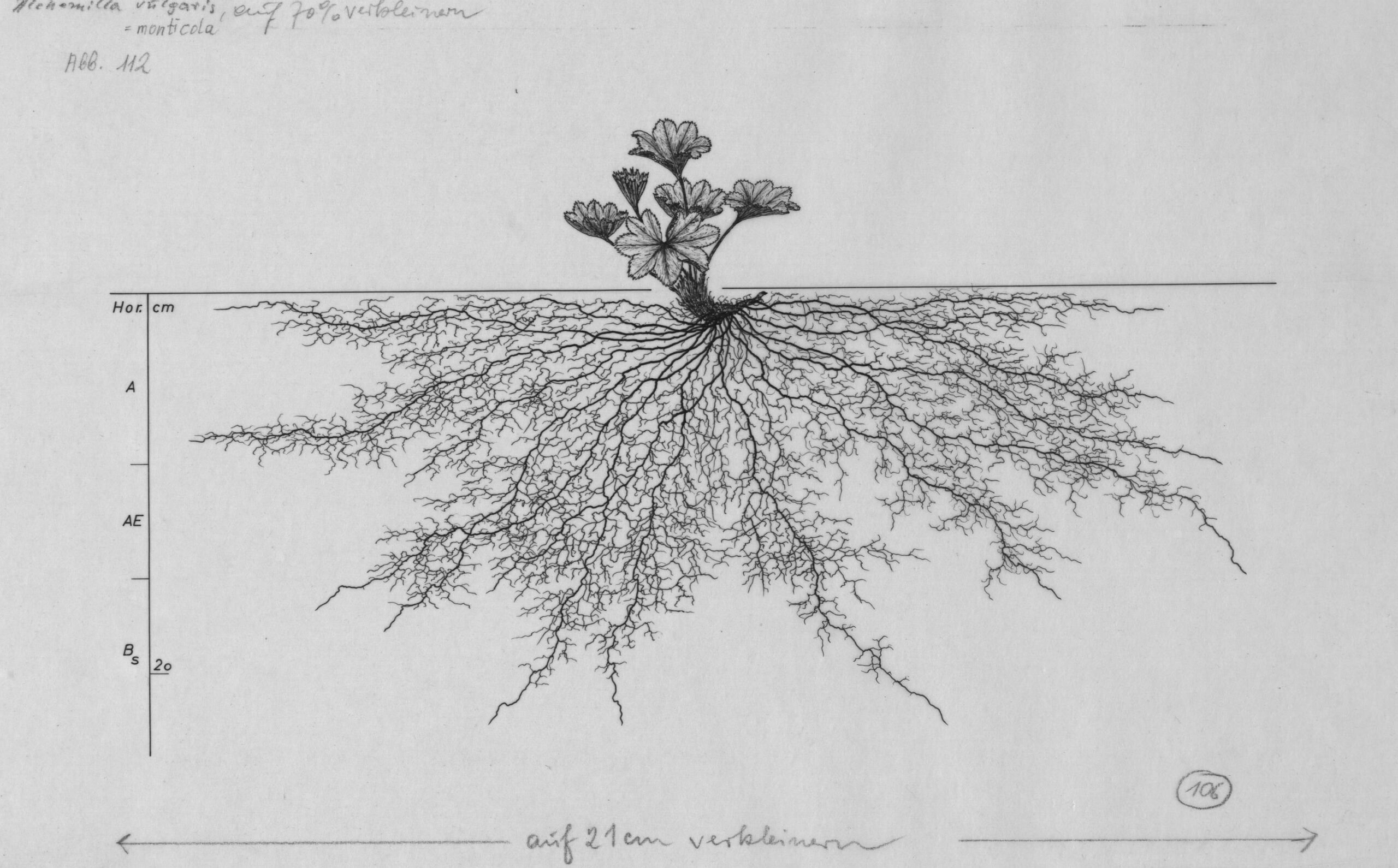

What goes on down below, underneath the soil? That you can see for yourself — and without having to pull up one of our fine flowering (or non-flowering) friends to do so — at Wageningen University’s online archive of root system drawings. “The outcome of 40 years of root system excavations in Europe,” says that site, the collection contains 1,180 diagrams of species from Abies alba (best known today as a kind of Christmas tree) to Zygophyllum xanthoxylon (a faintly scrubby-looking native of the arid and semi-arid regions of continents like Africa and Australia).

The site explains that “the drawings, their analysis and description were done by Univ. Prof. Dr. Erwin Lichtenegger (1928–2004) and Univ. Prof. Dr. Lore Kutschera (1917–2008), leader of Pflanzensoziologisches Institut, Klagenfurt, (now in Bad Goisern, Austria).”

Over the course of 40 years, writes The Washington Post’s Erin Blakemore, Lichtenegger and Kustchera “collaborated on an enormous ‘root atlas’ that maps the underground trajectories of common European plants.” Created through “a laborious system of digging up and documenting the intricate systems,” these drawings are “also art in their own right, honoring the beauty of a part of plants most never give that much thought.”

Even the least botanically aware among us knows that plants have roots, but how many of us are aware of the scale and complexity those roots can attain? “Root systems allow plants to gather the water and minerals they use to grow,” writes Blakemore. “As the root system grows, it creates more and more pathways that allow water to get into the deep subsoil, and fostering the growth of microbes that benefit other life. Strong root systems can prevent erosion, protecting the land on which they grow. And the structures allow the soil to capture carbon.” Thus root systems, never a particular locus of coolness, have the distinction of doing their part to fight climate change. And thanks to Lichtenegger and Kustchera’s drawings, they underscore the capacity of art to reveal worlds hidden to most of us. View all of the images here.

via Colossal

Related Content:

Two Million Wondrous Nature Illustrations Put Online by The Biodiversity Heritage Library

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.