We’ve experienced some mindblowing technological advances in the years following designers Charles and Ray Eames’ 1977 film Powers of Ten: A Film Dealing with the Relative Size of Things in the Universe and the Effect of Adding Another Zero.

And y’know, all sorts of innovative strides in the fields of medicine, communications, and environmental sustainability.

In the above video for the BBC, particle physicist Brian Cox pays tribute to the Eames’ celebrated eight-and-a-half-minute documentary short, and uses the discoveries of the last four-and-a-half decades to kick the can a bit further down the road.

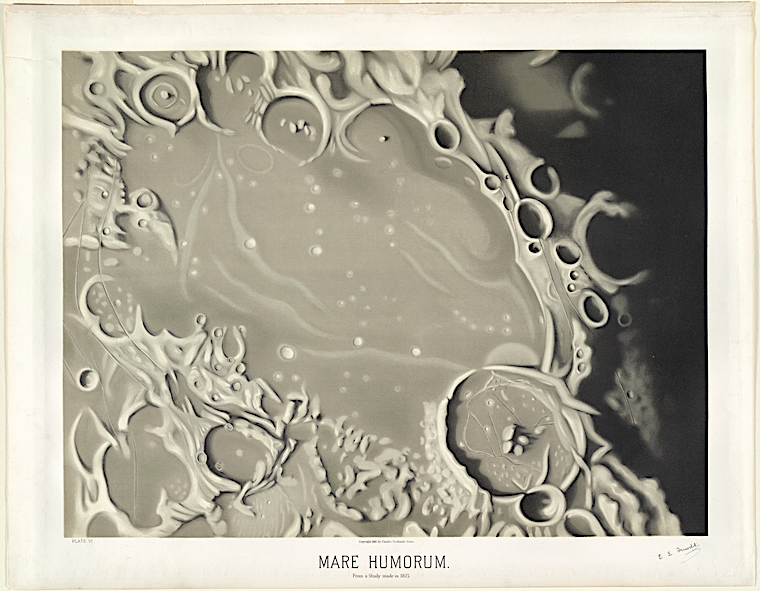

The original film helped ordinary viewers get a handle on the universe’s outer edges by telescoping up and out from a one-meter view of a picnic blanket in a Chicago park at the rate of one power of ten every 10 seconds.

Start with something everybody can understand, right?

At 100 (102) meters — slightly less than the total length of an American football field, the picnickers become part of the urban landscape, sharing their space with cars, boats at anchor in Lake Michigan, and a shocking dearth of fellow picnickers.

One more power of 10 and the picknickers disappear from view, eclipsed by Soldier Field, the Shedd Aquarium, the Field Museum and other longstanding downtown Chicago institutions.

At 1024 meters — 100 million light years away from the starting picnic blanket, the Eames butted up against the limits of the observable universe, at least as far as 1977 was concerned.

They reversed direction, hurtling back down to earth by one power of ten every two seconds. Without pausing for so much as handful of fruit or a slice of pie, they dove beneath the skin of a dozing picnicker’s hand, continuing their journey on a cellular, then sub-atomic level, ending inside a proton of a carbon atom within a DNA molecule in a white blood cell.

It still manages to put the mind in a whirl.

Sit tight, though, because, as Professor Cox points out, “Over 40 years later, we can show a bit more.”

2021 relocates the picnic blanket to a picturesque beach in Sicily, and forgoes the trip inside the human body in favor of Deep Space, though the method of travel remains the same — exponential, by powers of ten.

1013 meters finds us heading into interstellar space, on the heels of Voyagers 1 and 2, the twin spacecrafts launched the same year as the Eames’ Powers of Ten — 1977.

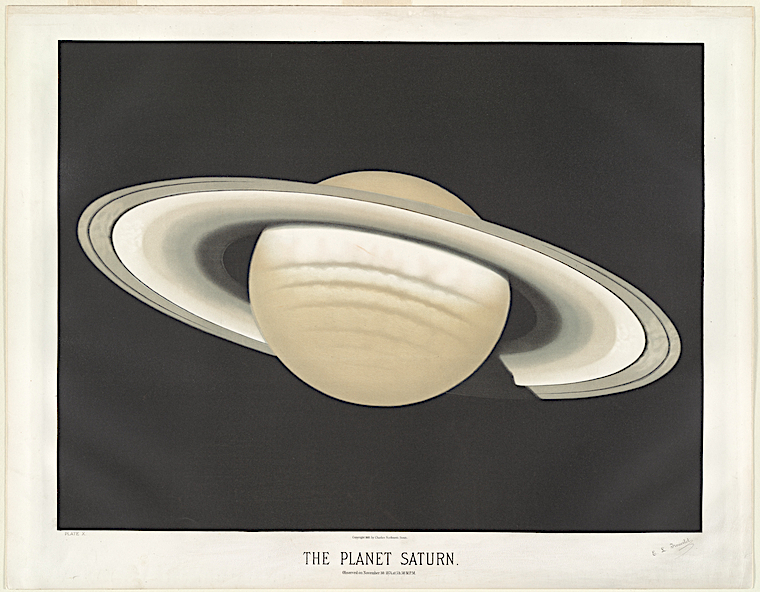

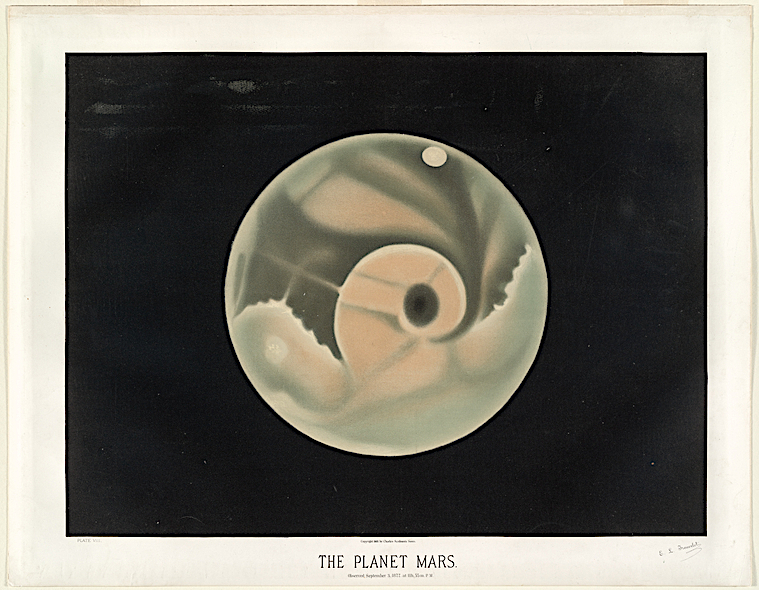

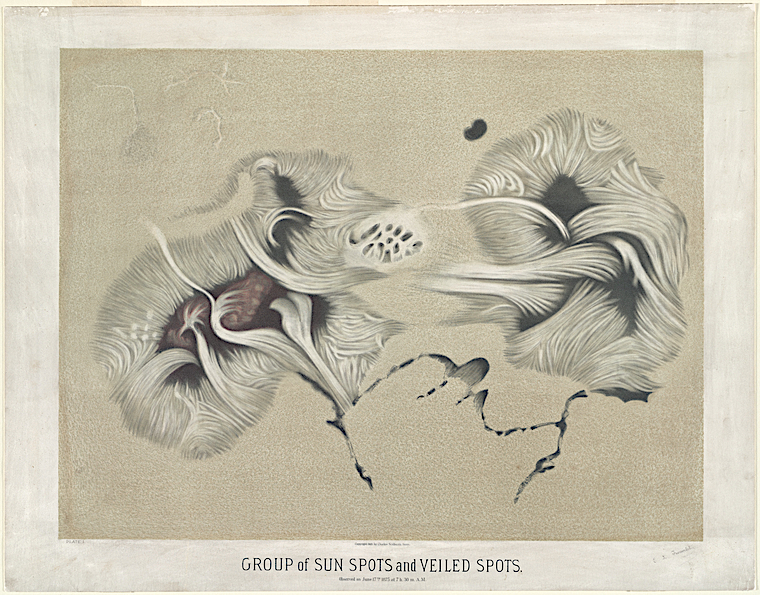

Having achieved their initial objective, the exploration of Jupiter and Saturn, these spacecrafts’ mission was expanded to Uranus, Neptune, and now, the outermost edge of the Sun’s domain. The data they, and other exploratory crafts, have sent back allow Cox and others in the scientific community to take us beyond the Eames’ outermost limits:

At 1026 meters, we switch our view to microwave. We can now see the current limit of our vision. This light forms a wall all around us. The light and dark patches show differences in temperature by fractions of a degree, revealing where matter was beginning to clump together to form the first galaxies shortly after the Big Bang. This light is known as the cosmic microwave background radiation.

1027 meters…1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000. Beyond this point, the nature of the Universe is truly uncharted and debated. This light was emitted around 380,000 years after the Big Bang. Before this time, the Universe was so hot that it was not transparent to light. Is there simply more universe out there, yet to be revealed? Or is this region still expanding, generating more universe, or even other universes with different physical properties to our own? How will our understanding of the Universe have changed by 2077? How many more powers of ten are out there?

According to NASA, the Voyager crafts have sufficient power and fuel to keep their “current suite of science instruments on” for another four years, at least. By then, Voyager 1 will be about 13.8 billion miles, and Voyager 2 some 11.4 billion miles from the Sun:

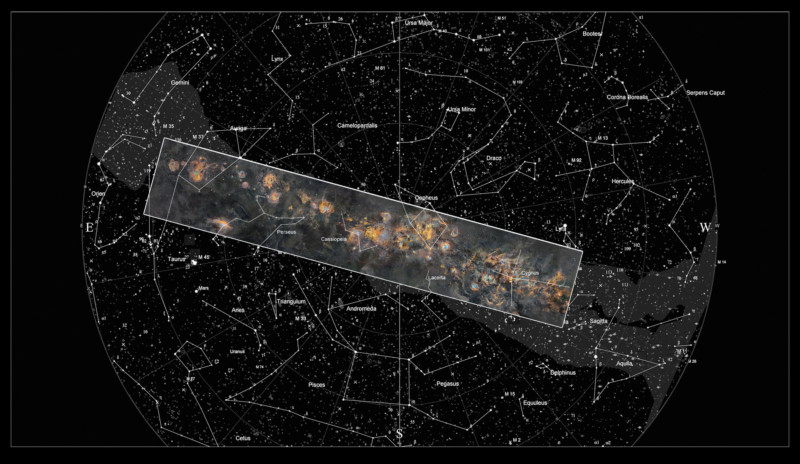

In about 40,000 years, Voyager 1 will drift within 1.6 light-years (9.3 trillion miles) of AC+79 3888, a star in the constellation of Camelopardalis which is heading toward the constellation Ophiuchus. In about 40,000 years, Voyager 2 will pass 1.7 light-years (9.7 trillion miles) from the star Ross 248 and in about 296,000 years, it will pass 4.3 light-years (25 trillion miles) from Sirius, the brightest star in the sky. The Voyagers are destined—perhaps eternally—to wander the Milky Way.

If this dizzying information makes you yearn for 1987’s simple pleasures, this Wayback Machine link includes a fun interactive for the original Powers of Ten. Click the “show text” option on an exponential slider tool to consider the scale of each stop in historic and tangible context.

Related Content:

Carl Sagan’s “The Pale Blue Dot” Animated

Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.