If you are a frequent reader of Open Culture, or the many blogs we tend to read — especially those concerned with the rare, unusual, and obscure — it’s likely you’ve encountered some of the books in The Madman’s Library, Edward Brooke-Hitching’s fantastic new volume of literary oddities. If not, you’re probably familiar with a few of the categories he identifies under his subtitle, “The Strangest Books, Manuscripts and Other Literary Curiosities from History.” These include “Books Made of Flesh and Blood,” such as a Qur’an written in 50 pints of Saddam Hussein’s blood. If such artifacts don’t qualify as “literary curiosities,” it’s hard to know what does.

Brooke-Hitching grants the designation “curiosity” is subjective, and culturally determined, “but after nearly a decade of searching through catalogues of libraries, auction houses and antiquarian book dealers around the world,” he writes in his introduction,” works of undeniable peculiarity leapt out.”

Or as he tells Smithsonian in an interview, “the more books you see, the more your radar is sensitive to something that pings with its strangeness.” He pulls out the first book in his bag as an example: a self-published collection of poetry by Charlie Sheen.

Perhaps few other people have laid eyes on such an enormous collection of oddball bibliographic treasures. These are not only books made of strange — and even deadly — materials; they are also books whose contents or histories are just plain weird.

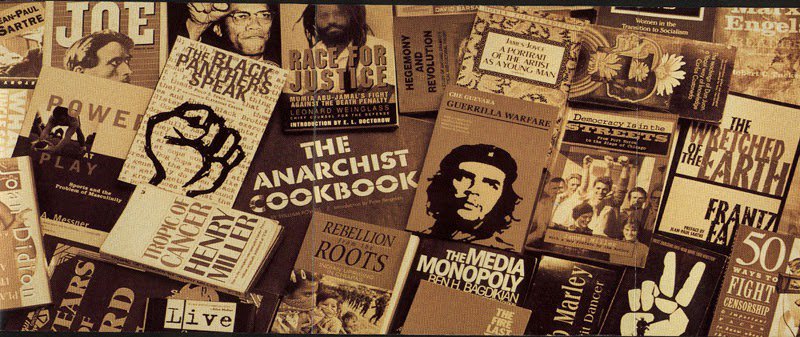

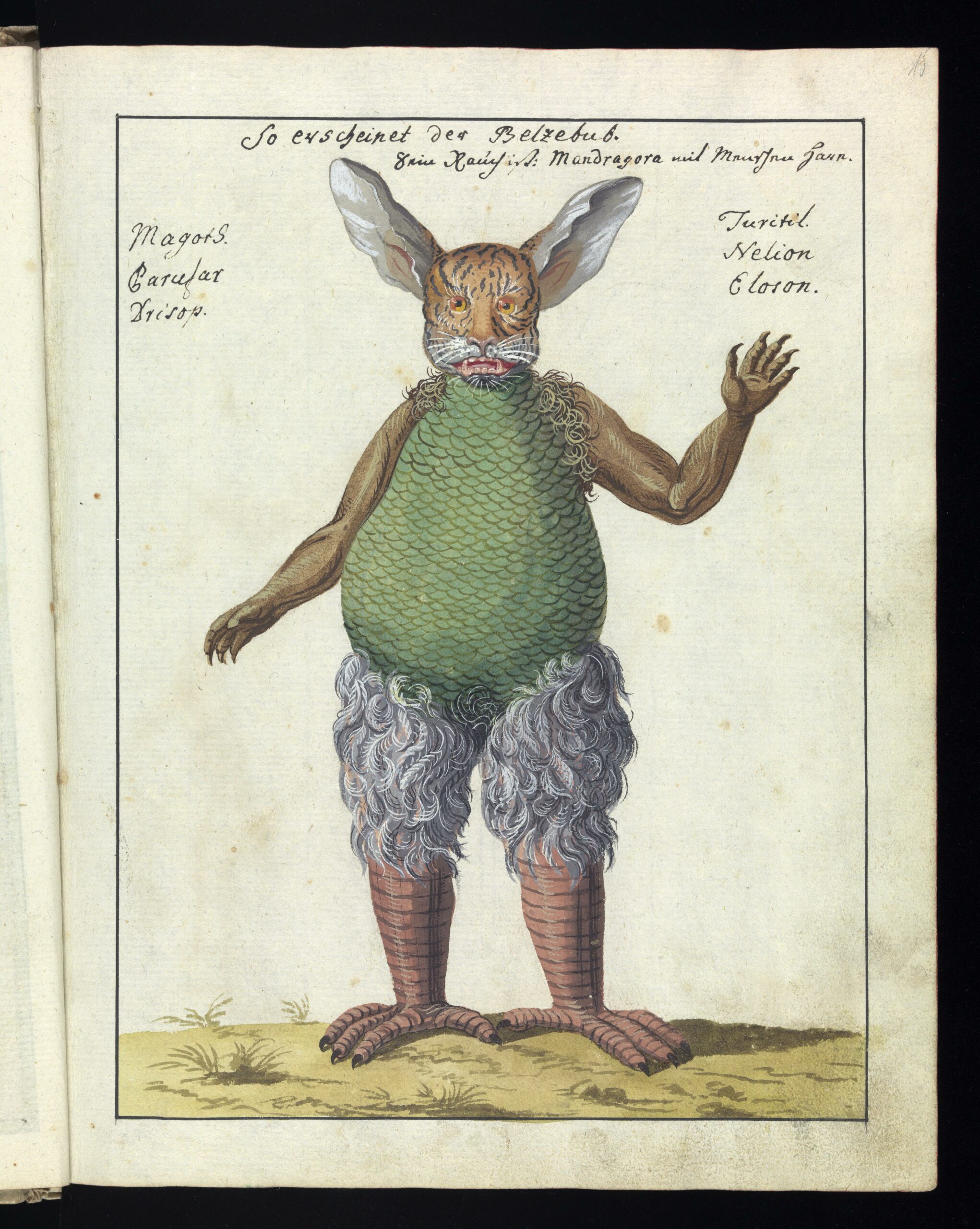

The chapter ‘Curious Collections’… features similar projects of obsessive dedication, from medieval manuscripts of fantastic beasts, and guides to criminal slang of Georgian London (with plenty of lascivious highlights provided), to Captain Cook’s secret ‘atlas of cloth’ and the unexpectedly homicidal story of the origin of the Oxford English dictionary. Elsewhere, ‘Literary Hoaxes’ presents the best of the ancient tradition of deceptive writing–lies in book form–whether it be for satire, self promotion or as an instrument of revenge.

Of the latter, Brooke-Hitching cites Jonathan Swift’s series of pamphlets written under a pseudonym, “a successful campaign to convince all of London of the premature death of a charlatan prophet he despised.” In a chapter titled ‘Works of the Supernatural,’ Brooke-Hitching gives us the example of W.B. Yeats’ wife George, who transcribed “4000 pages of spiritual dictation in the first three years of their marriage.” Her automatic writing was published in a compilation called A Vision in 1925, but “through seven editions it was only Yeats’ name” on the title page.

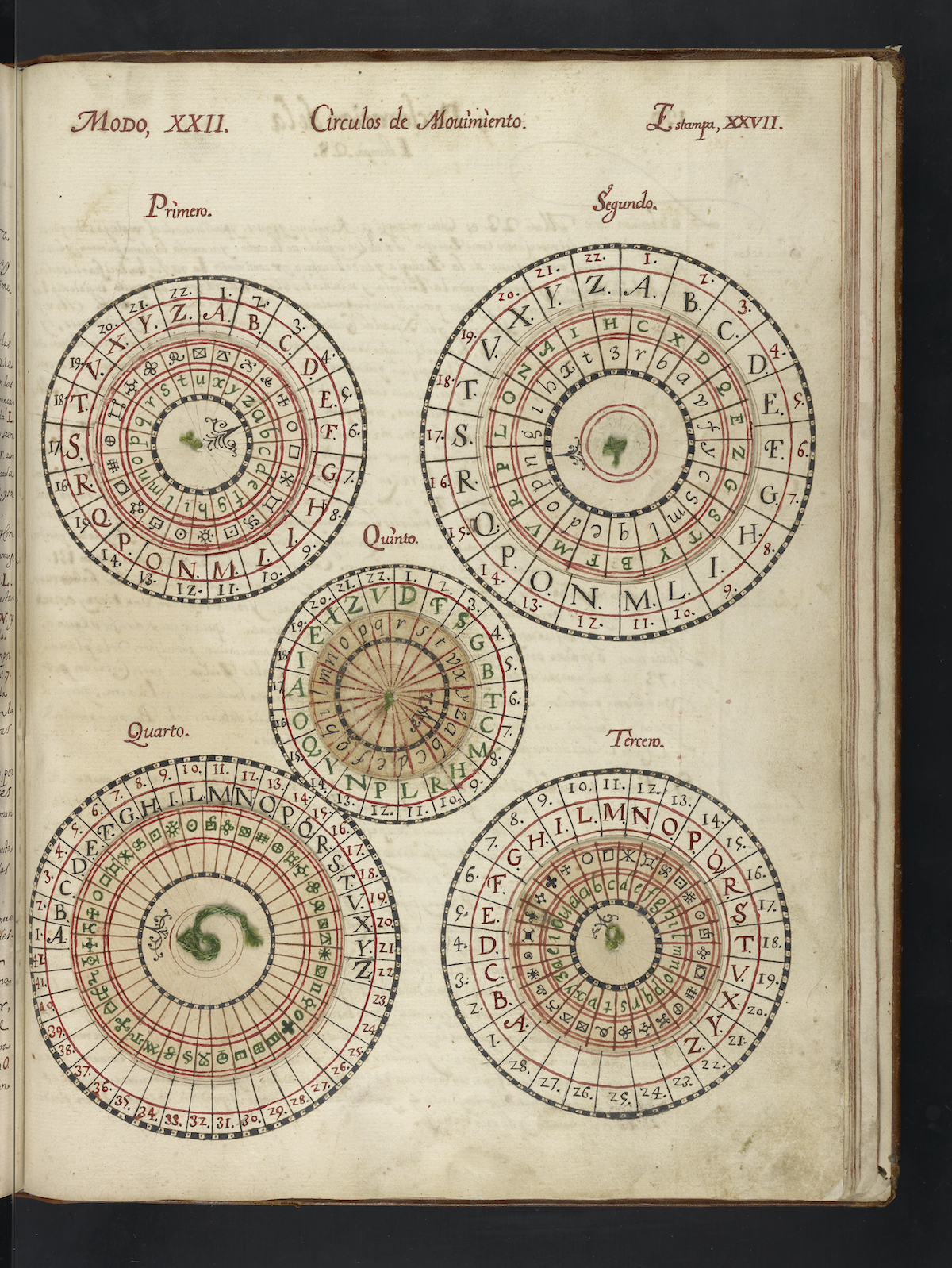

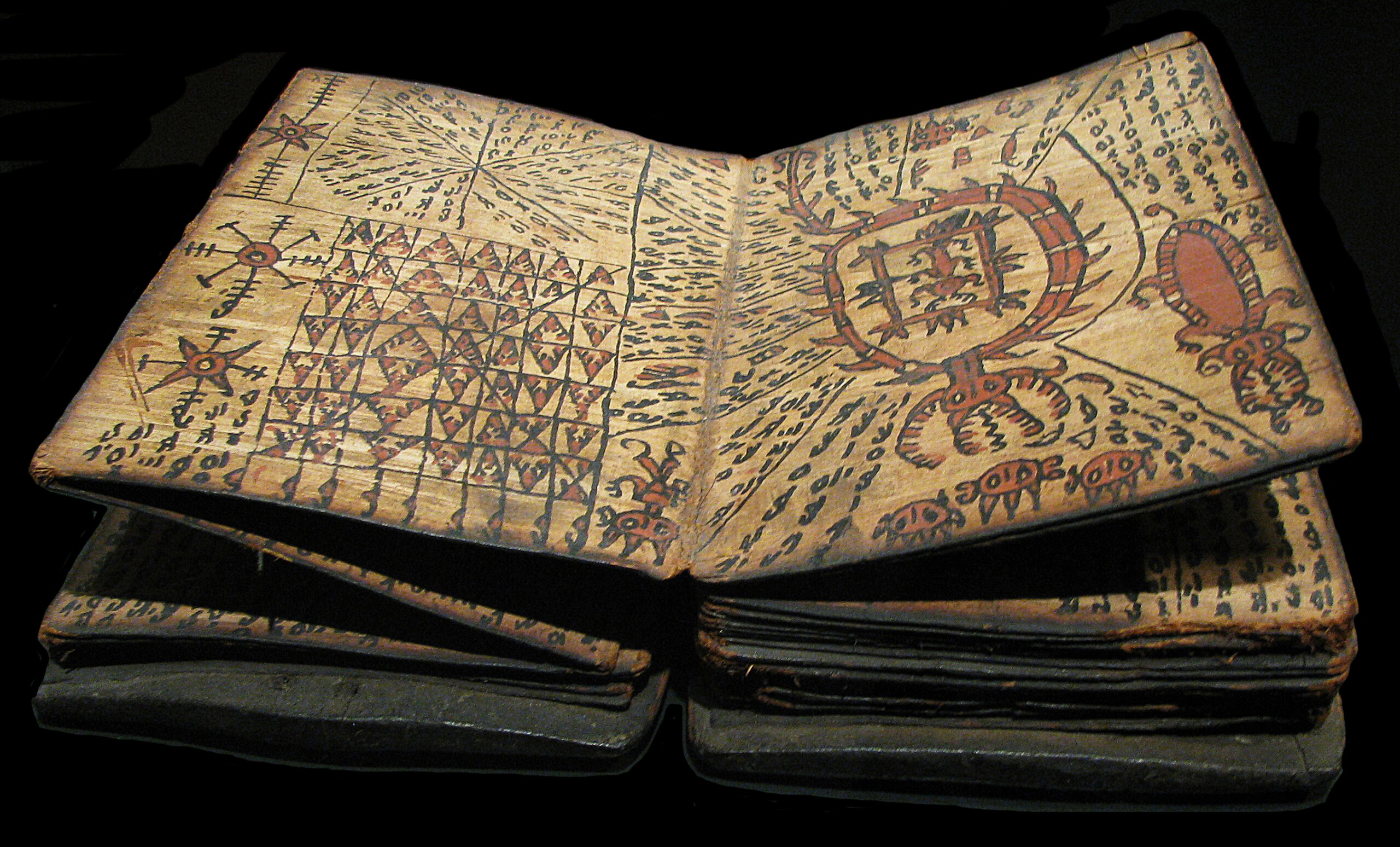

There are ‘Books that aren’t Books,’ such as a skull inscribed with a prayer and a collection of autobiographical fragments embroidered on the linen jacket of an incarcerated seamstress; there are ‘Cryptic Books” like the Voynich Manuscript and poetry written in code. Part literary detective story, part bibliographic odyssey through time, part literary curiosity all its own (though more of the coffee-table variety), The Madman’s Library is a feast for bibliophiles and oddballs of all kinds. Pick up a copy here and see several more of exceptionally curious books over at Smithsonian.

Related Content:

A Medieval Book That Opens Six Different Ways, Revealing Six Different Books in One

Wonderfully Weird & Ingenious Medieval Books

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness