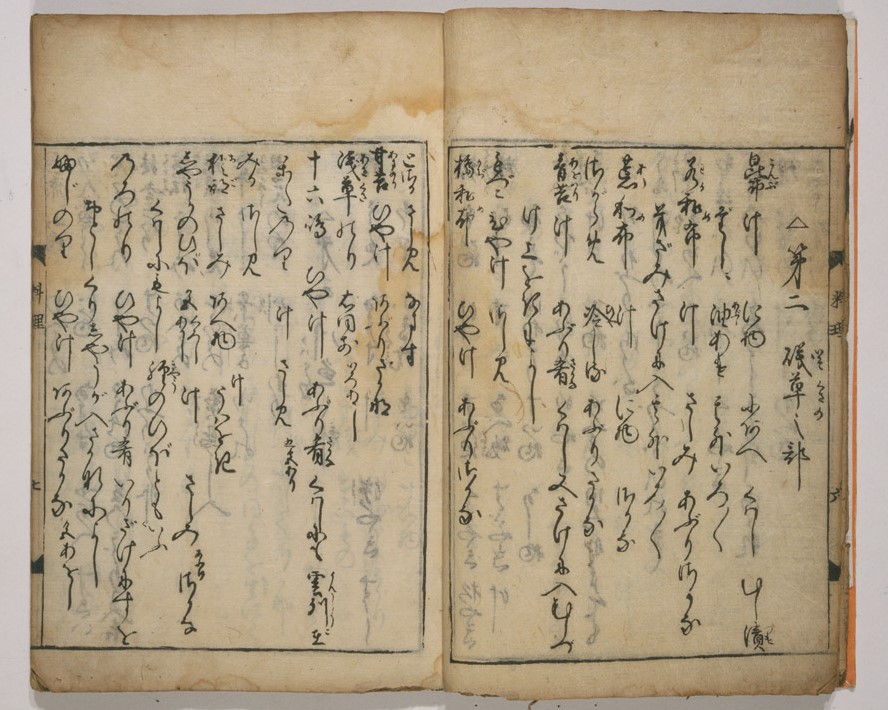

Like most Japanese masters of ukiyo‑e woodblock art, Katsushika Hokusai is best known mononymously. But he’s even better known by his work — and by one piece of work in particular, The Great Wave off Kanagawa. Even those who’ve never heard the name Hokusai have seen that print, arresting in its somehow calm turbulence, or at least they’ve seen one of its countless modern parodies and tributes (most recently, a large-scale homage in the medium of LEGO). But when he died in 1849, the prolific and long-lived artist left behind a body of work amounting to more than 30,000 paintings, sketches, prints, and illustrations (as well as a how-to-draw book).

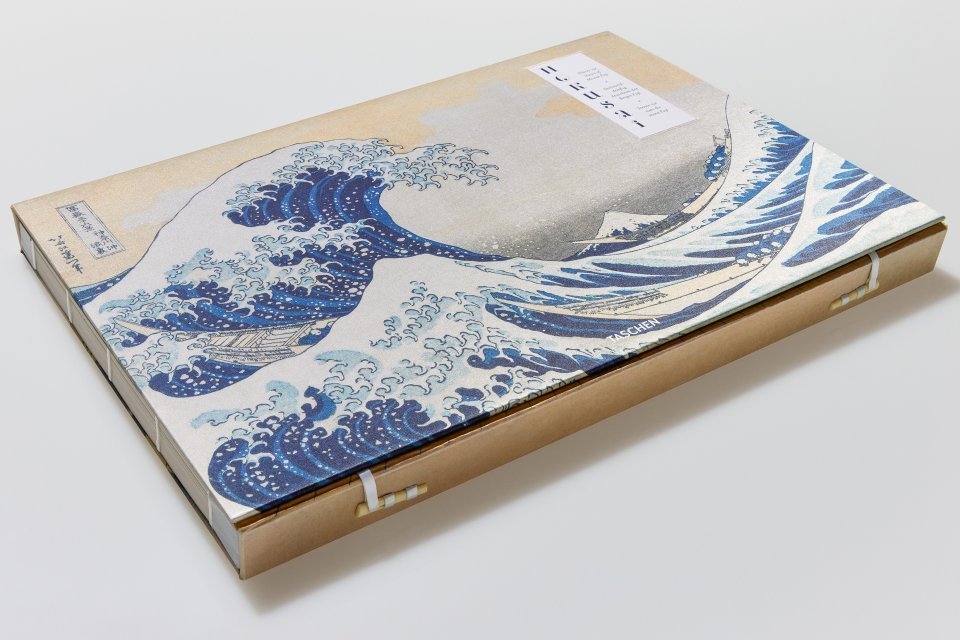

None of those 30,000 works are quite as famous as his Great Wave off Kanagawa, but very few indeed are as ambitions as the series to which it belongs, Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji. It is that two-year project, the artistic fruit of an obsession with Fuji and its environs, that Taschen has taken as the material for their new book Hokusai: Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji.

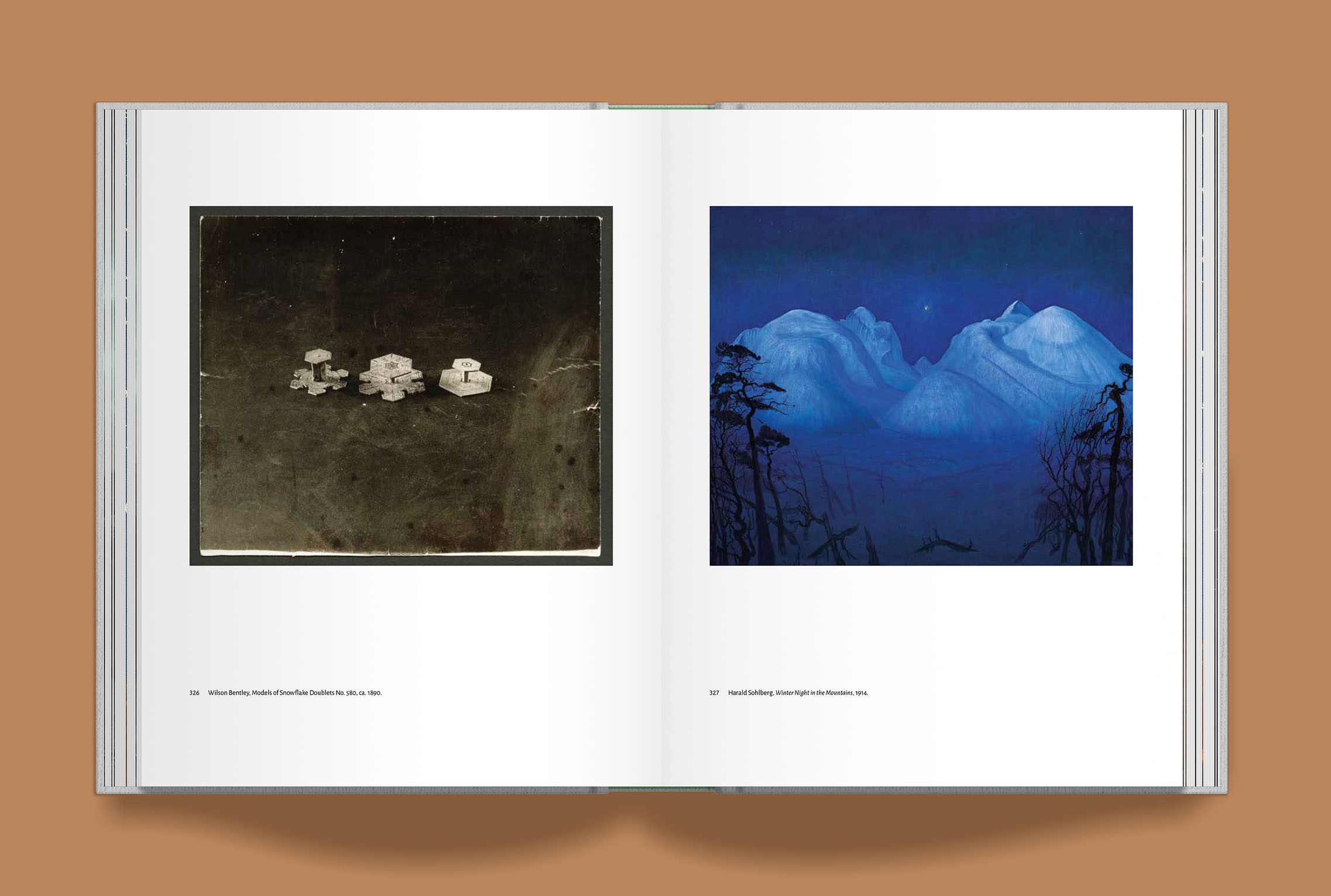

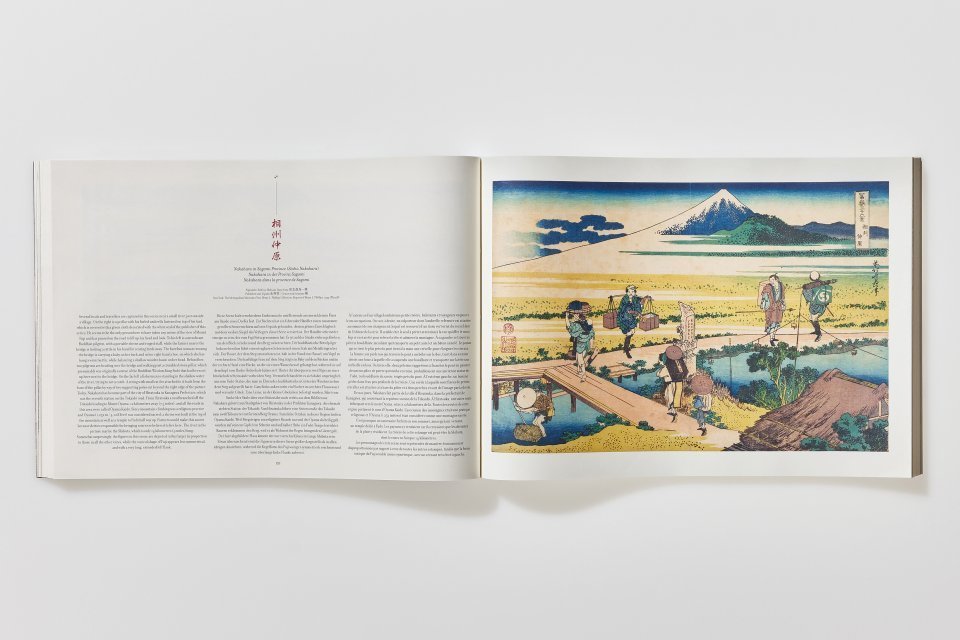

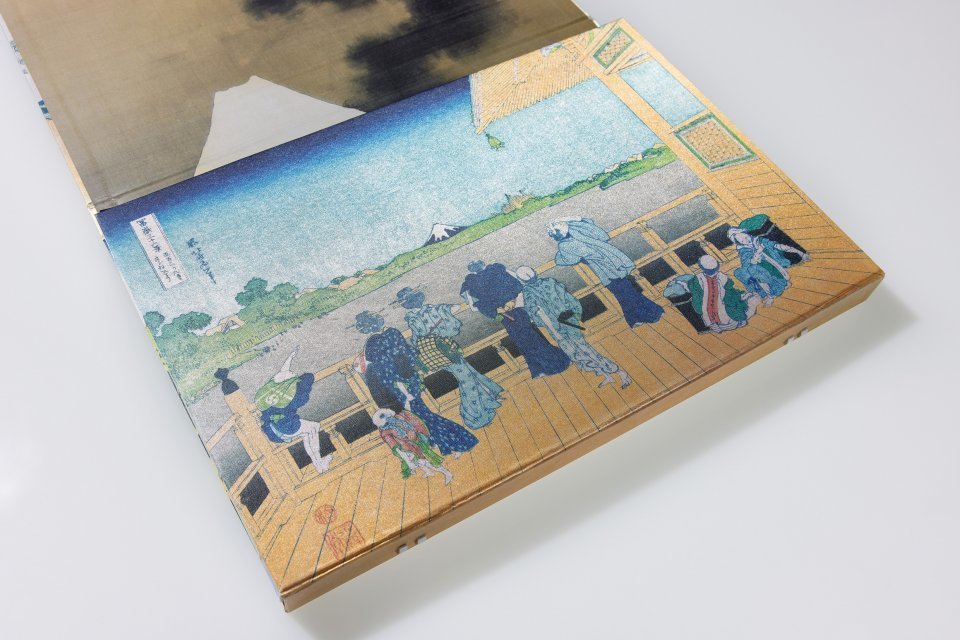

Produced in a 224-page “XXL edition,” it gathers “the finest impressions from institutions and collections worldwide in the complete set of 46 plates alongside 114 color variations” — all sewn together, appropriately, with “Japanese binding.”

Not only does the book reproduce Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji with Taschen’s signature attention to image quality, it presents The Great Wave off Kanagawa in a way few actually see it: in context. For that most widely published of all Hokusai prints launched the series, which continued on to Fine Wind, Clear Morning, Thunderstorm Beneath the Summit, and Kajikazawa in Kai Province, that last being an image held in especially high esteem by ukiyo‑e enthusiasts. One such enthusiast, east Asian art historian Andreas Marks, has performed this book’s editing and writing, as he did with Taschen’s previous Japanese Woodblock Prints (1680–1938). Experiencing the whole of Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, more than one reader will no doubt become as transfixed by Hokusai as Hokusai was by his homeland’s most beloved mountain. You can pick up a copy of Hokusai: Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji here.

Related Content:

See Classic Japanese Woodblocks Brought Surreally to Life as Animated GIFs

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.