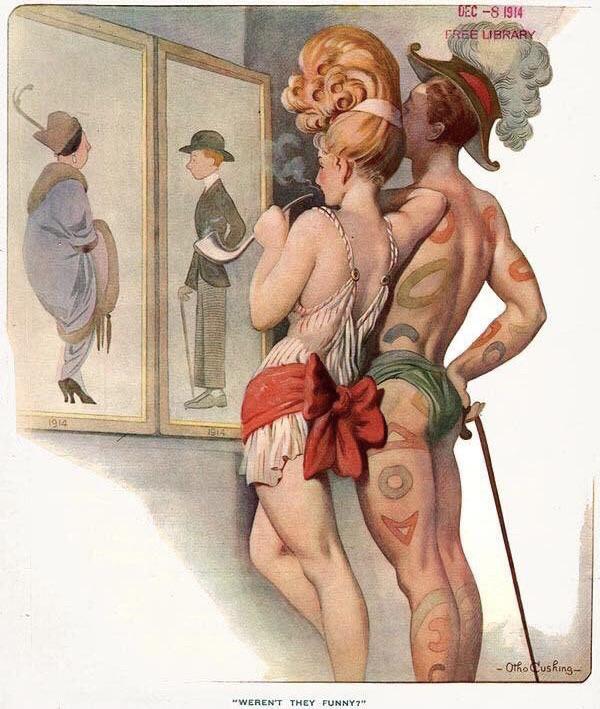

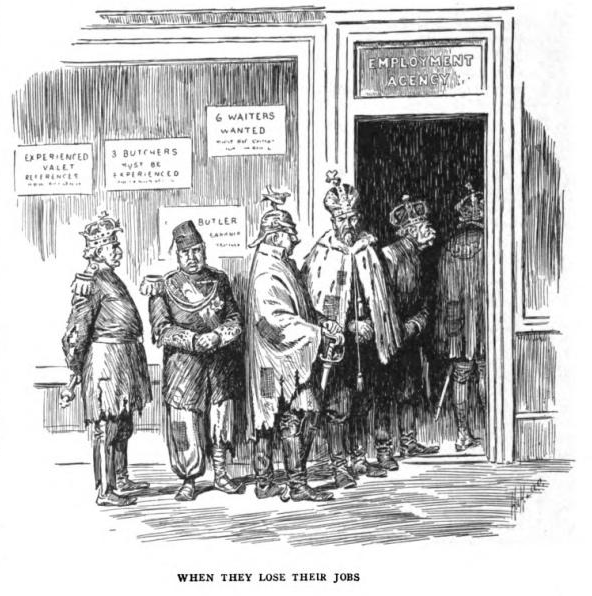

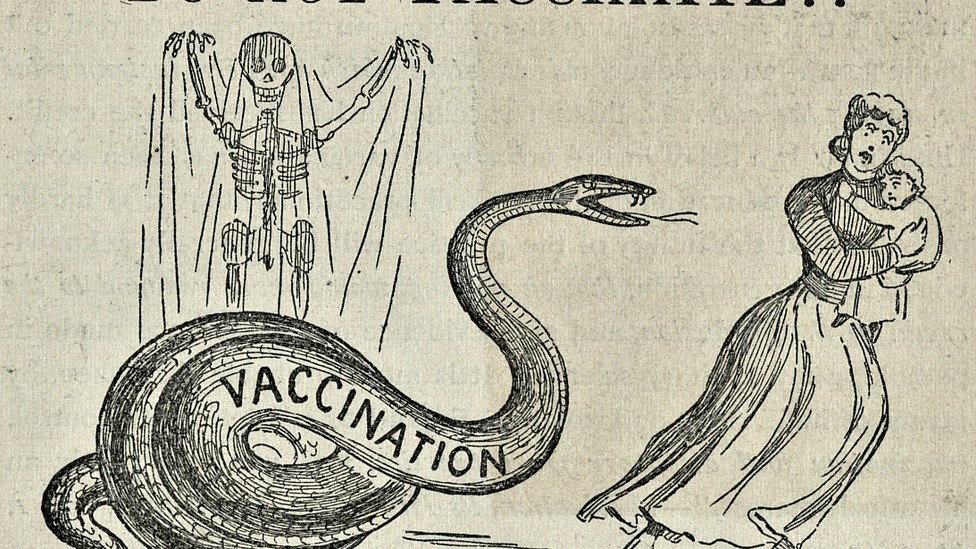

A cartoon from a December 1894 anti-vaccination publication (Courtesy of The Historical Medical Library of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia)

For well over a century people have queued up to get vaccinated against polio, smallpox, measles, mumps, rubella, the flu or other epidemic diseases. And they have done so because they were mandated by schools, workplaces, armed forces, and other institutions committed to using science to fight disease. As a result, deadly viral epidemics began to disappear in the developed world. Indeed, the vast majority of people now protesting mandatory vaccinations were themselves vaccinated (by mandate) against polio, smallpox, measles, mumps, rubella, etc., and hardly any of them have contracted those once-common diseases. The historical argument for vaccines may not be the most scientific (the science is readily available online). But history can act as a reliable guide for understanding patterns of human behavior.

In 1796, Scottish physician Edward Jenner discovered how an injection of cowpox-infected human biological material could make humans immune to smallpox. For the next 100 years after this breakthrough, resistance to inoculation grew into “an enormous mass movement,” says Yale historian of medicine Frank Snowden. “There was a rejection of vaccination on political grounds that it was widely considered as another form of tyranny.”

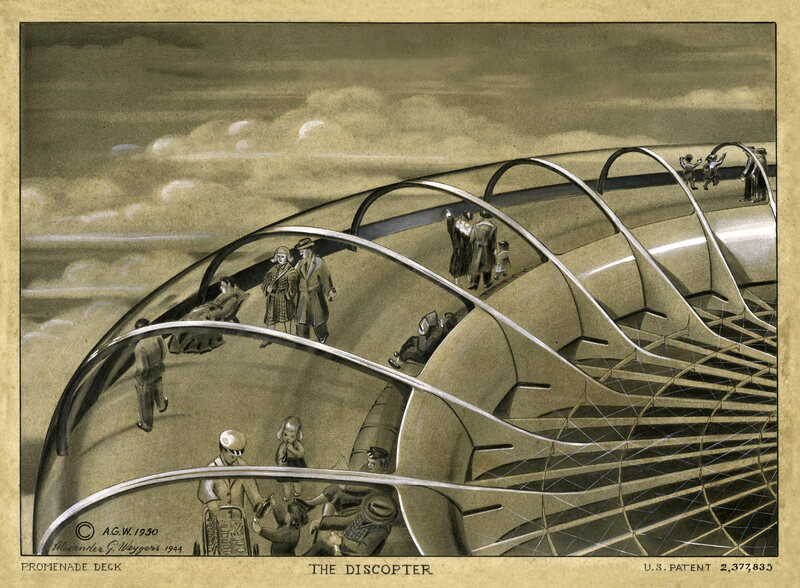

Fears that injections of cowpox would turn people into mutants with cow-like growths were satirized as early as 1802 by cartoonist James Gilray (below). While the anti-vaccination movement may seem relatively new, the resistance, refusal, and denialism are as old as vaccinations to infectious disease in the West.

Image via Wikimedia Commons

“In the early 19th century, British people finally had access to the first vaccine in history, one that promised to protect them from smallpox, among the deadliest diseases in the era,” writes Jess McHugh at The Washington Post. Smallpox killed around 4,000 people a year in the UK and left hundreds more disfigured or blinded. Nonetheless, “many Britons were skeptical of the vaccine.… The side effects they dreaded were far more terrifying: blindness, deafness, ulcers, a gruesome skin condition called ‘cowpox mange’ — even sprouting hoofs and horns.” Giving a person one disease to frighten off another one probably seemed just as absurd a notion as turning into a human/cow hybrid.

Jenner’s method, called variolation, was outlawed in 1840 as safer vaccinations replaced it. By 1867, all British children up to age 14 were required by law to be vaccinated against smallpox. Widespread outrage resulted, even among prominent physicians and scientists, and continued for decades. “Every day the vaccination laws remain in force,” wrote scientist Alfred Russel Wallace in 1898, “parents are being punished, infants are being killed.” In fact, it was smallpox claiming lives, “more than 400,000 lives per year throughout the 19th century, according to the World Health Organization,” writes Elizabeth Earl at The Atlantic. “Epidemic disease was a fact of life at the time.” And so it is again. Covid has killed almost 800,000 people in the U.S. alone over the past two years.

Then as now, medical quackery played its part in vaccine refusal — in this case a much larger part. “Never was the lie of ‘the good old days’ more clear than in medicine,” Greig Watson writes at BBC News. “The 1841 UK census suggested a third of doctors were unqualified.” Common causes of illness in an 1848 medical textbook included “wet feet,” “passionate fear or rage,” and “diseased parents.” Among the many fiery lectures, caricatures, and pamphlets issued by opponents of vaccination, one 1805 tract by William Rowley, a member of the Royal College of Physicians, alleged that the injection of cowpox could mar an entire bloodline. “Who would marry into any family, at the risk of their offspring having filthy beastly diseases?” it asked hysterically.

Then, as now, religion was a motivating factor. “One can see it in biblical terms as human beings created in the image of God,” says Snowden. “The vaccination movement injecting into human bodies this material from an inferior animal was seen as irreligious, blasphemous and medically wrong.” Granted, those who volunteered to get vaccinated had to place their faith in the institutions of science and government. After medical scandals of the recent past like the Tuskegee experiments or Thalidomide, that can be a big ask. In the 19th century, says medical historian Kristin Hussey, “people were asking questions about rights, especially working-class rights. There was a sense the upper class were trying to take advantage, a feeling of distrust.”

The deep distrust of institutions now seems intractable and fully endemic in our current political climate, and much of it may be fully warranted. But no virus has evolved — since the time of the Jenner’s first smallpox inoculation — to care about our politics, religious beliefs, or feelings about authority or individual rights. Without widespread vaccination, viruses are more than happy to exploit our lack of immunity, and they do so without pity or compunction.

Related Content:

Dying in the Name of Vaccine Freedom

How Vaccines Improved Our World In One Graphic

How Do Vaccines (Including the COVID-19 Vaccines) Work?: Watch Animated Introductions

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness