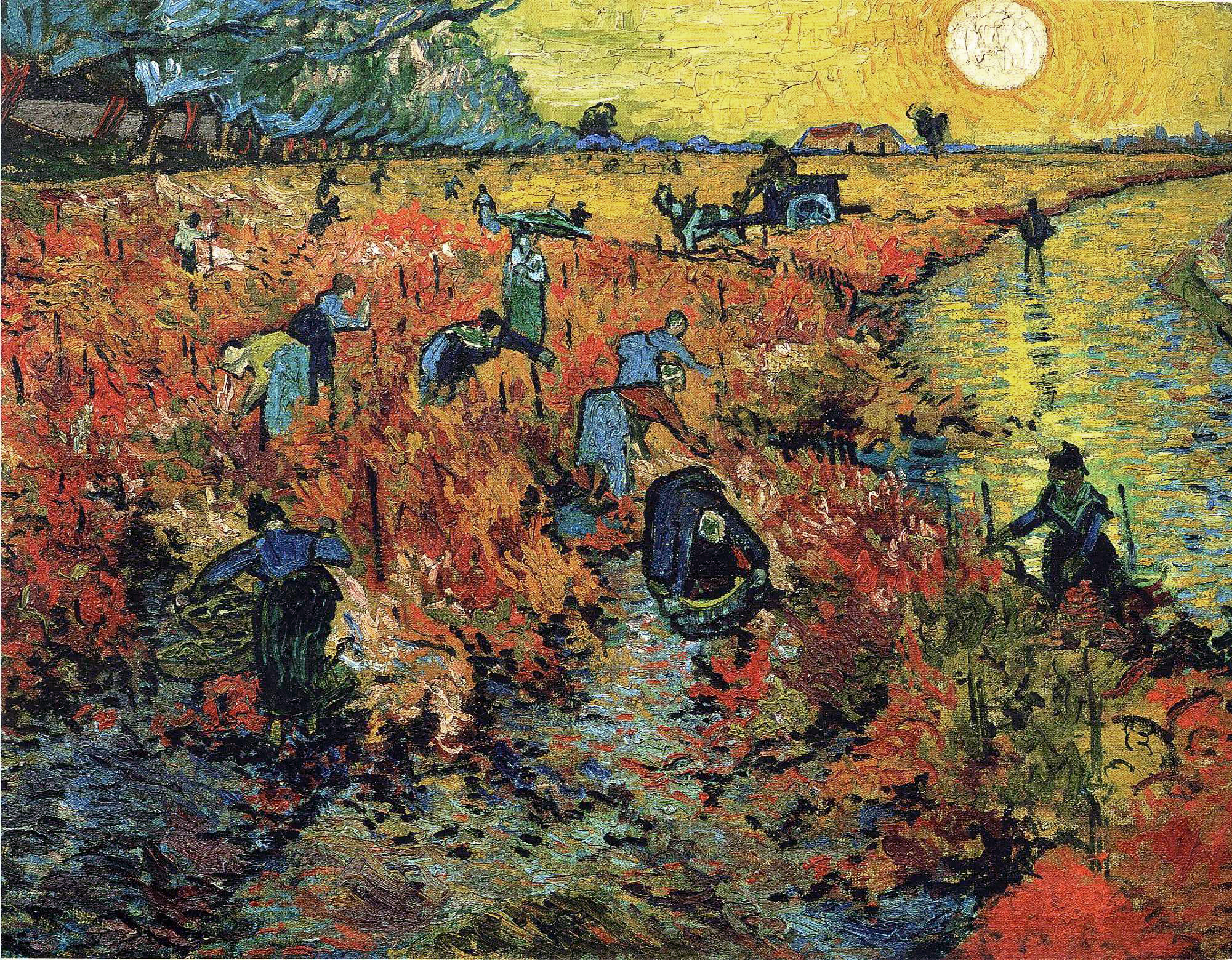

It may have crossed your mind, while beholding paintings of Vincent van Gogh, that you’d like to own one yourself someday. If so, you’ll have to get in line with more than a few billionaires, and even they may never see one go up on the auction block. This would probably come as a surprise to van Gogh himself, who died destitute — and practically unknown — after an artistic career of just ten years. In that time, he managed to sell exactly one painting, at least according to certain definitions of “sell.” Van Gogh did barter paintings for food and art supplies, and he did accept commissions, beginning with one from his art-dealer uncle Cor. But as for sales made to non-relatives through an official show, we only know of one: La vigne rouge.

Known in English as The Red Vineyards near Arles, or simply The Red Vineyard, the painting depicts a landscape van Gogh came across “on a late afternoon walk with Paul Gauguin on 28 October 1888, five days after his friend’s arrival in Arles.” So writes Martin Bailey at The Art Newspaper, who adds that “picking the grapes normally takes place in September in Provence, but the harvest seems to have been late that year.”

To his brother Theo, Vincent described the scene thus: “A red vineyard, completely red like red wine. In the distance it became yellow, and then a green sky with a sun, fields violet and sparkling yellow here and there after the rain in which the setting sun was reflected.” The artist was not, however, moved to set up his canvas then and there; rather, he painted the vineyard the next month, from memory.

Vincent let Theo hang the resulting canvas in his Paris apartment until he asked for it back in order to exhibit it in the annual Brussels show put on by a group called Les Vingt in early 1890. The Red Vineyards’ buyer was one of their number, a certain Anna Boch, the sister of van Gogh’s colleague in impressionism (and onetime portrait subject) Eugène Boch. Though she was no relation, Anna did pay full sticker price for the painting, and van Gogh later expressed some regret about not giving her a “friend’s price.” But whatever it cost her, it was surely a steal compared to its value today, after its purchase by a Russian collector, its revolutionary expropriation, and its long Soviet suppression followed by proud exhibition at Moscow’s Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts — which, owing to the painting’s fragility, won’t even lend it out.

Related content:

1,500 Paintings & Drawings by Vincent van Gogh Have Been Digitized & Put Online

Vincent Van Gogh’s The Starry Night: Why It’s a Great Painting in 15 Minutes

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.

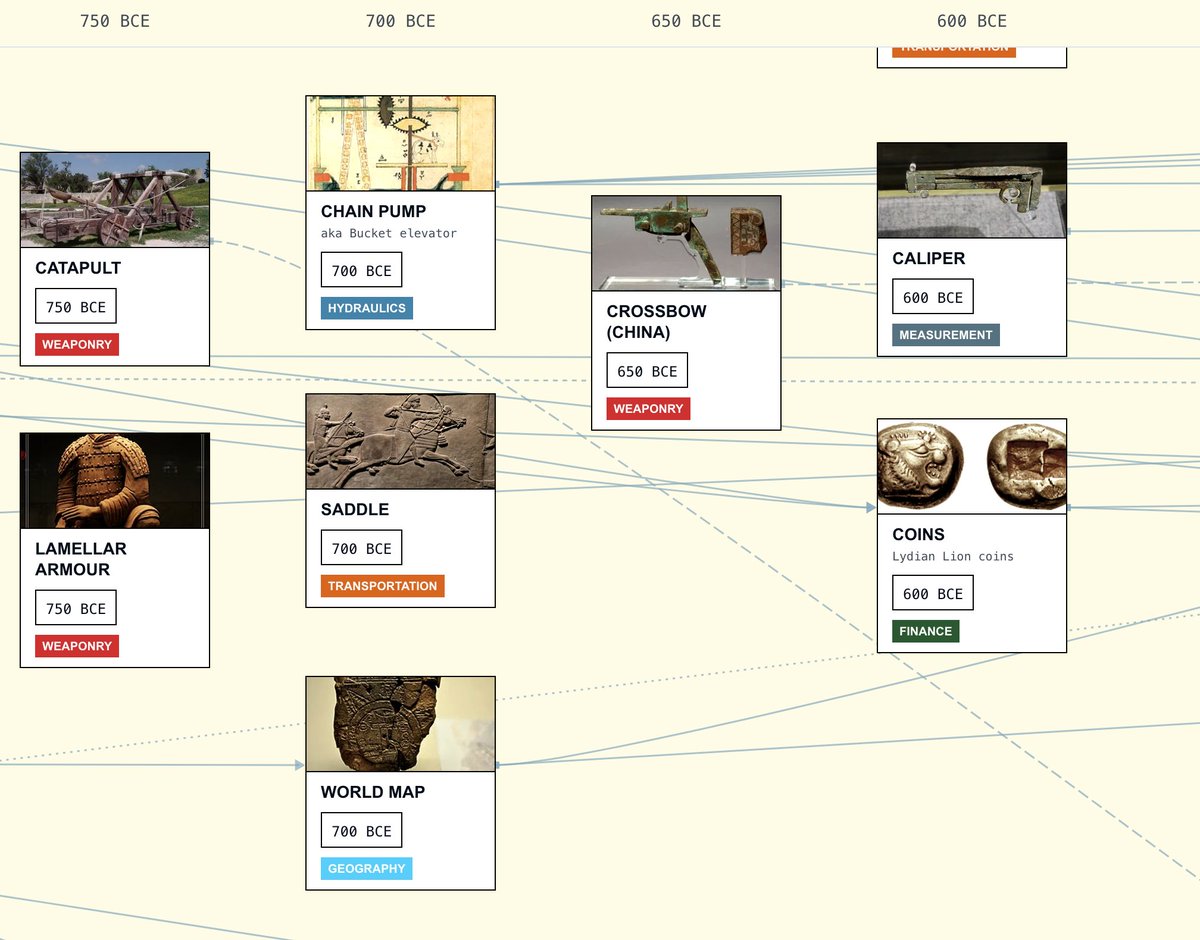

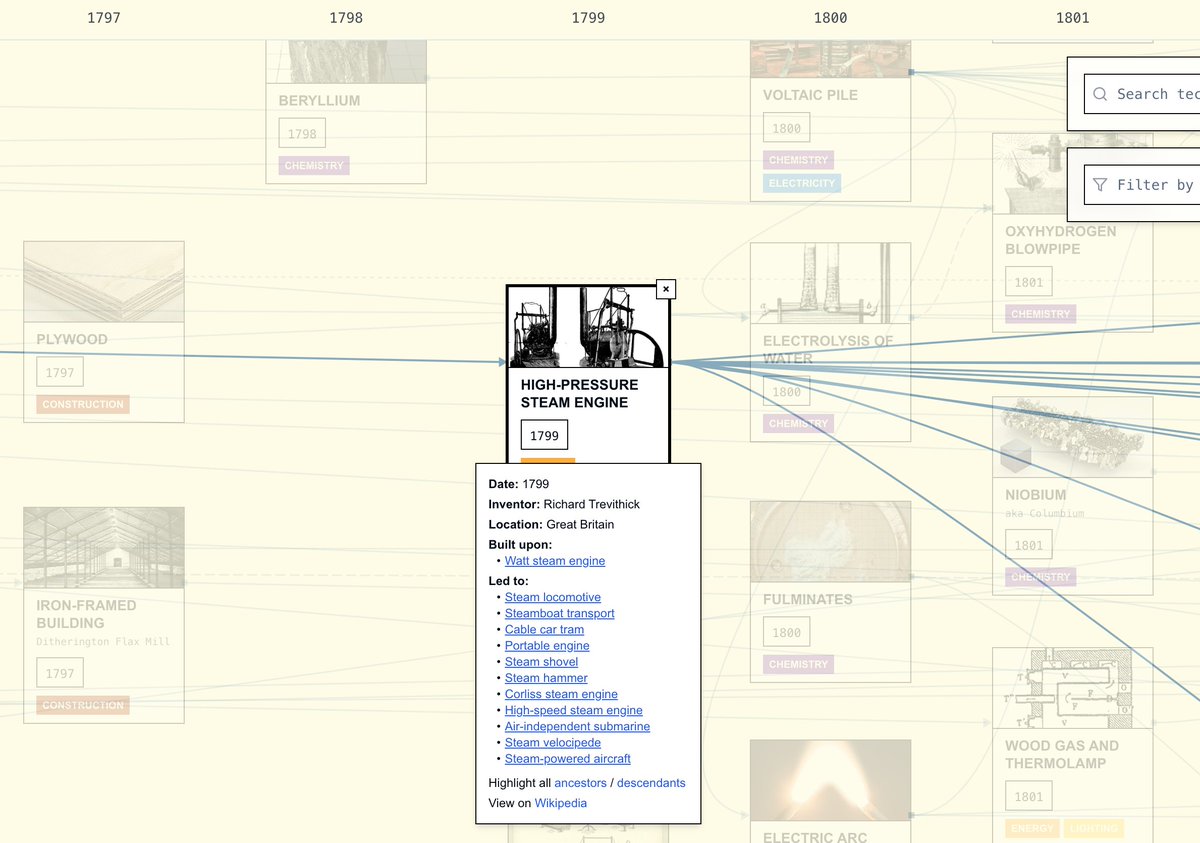

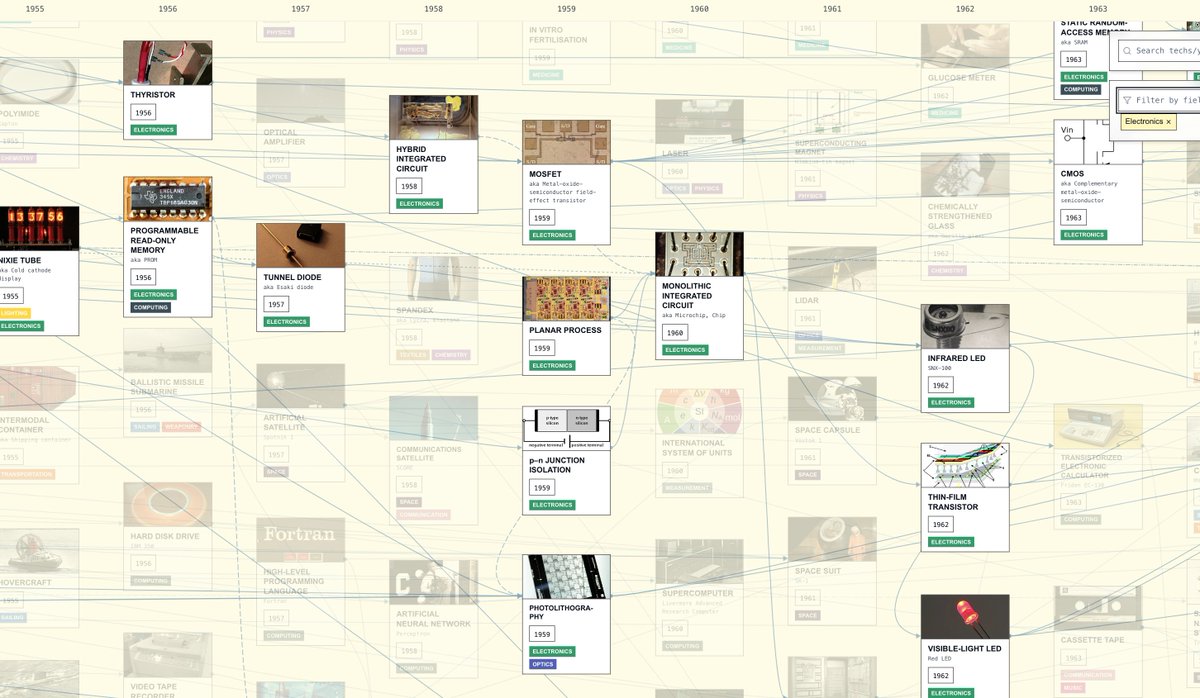

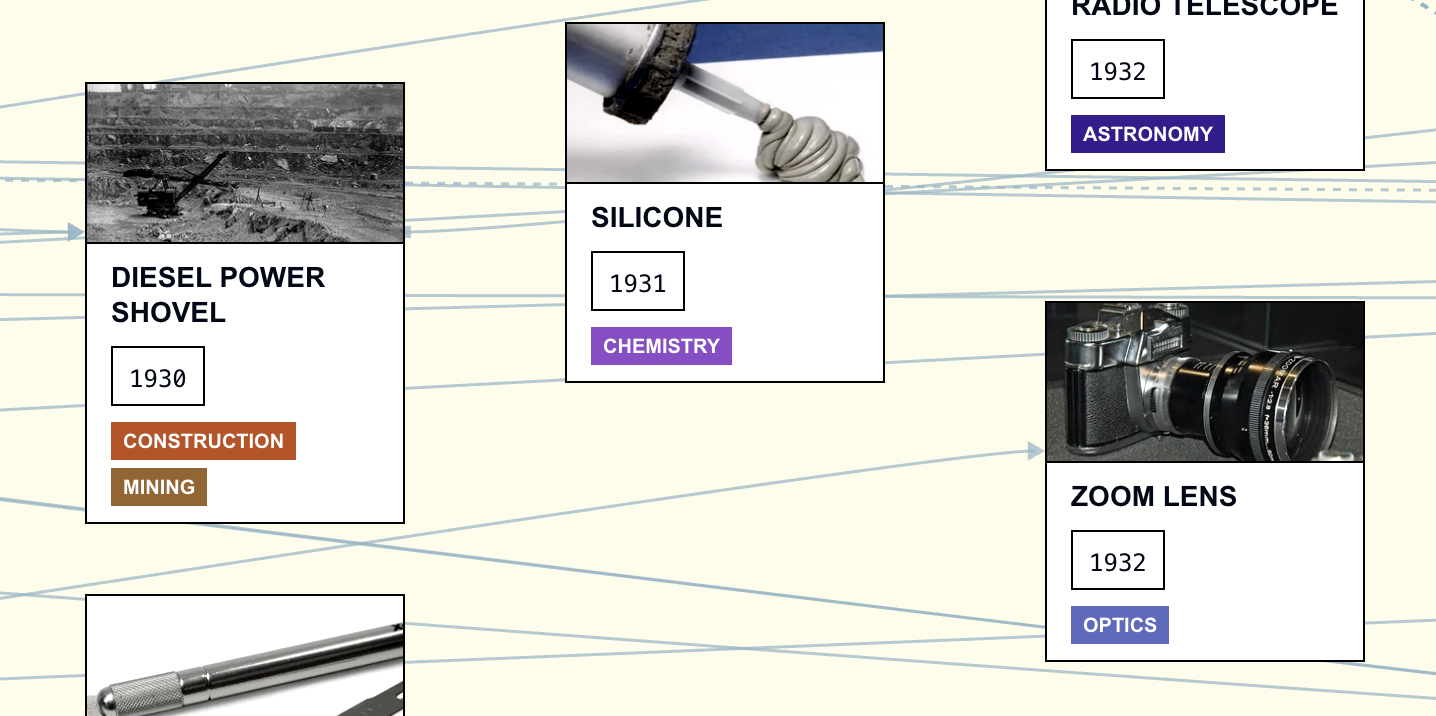

but a sense of how much of that knowledge we lack. Our civilization has made its way from stone tools to robotaxis, mRNA vaccines, and LLM chatbots; we’d all be better able to inhabit it with even a slightly clearer idea of how it did so. Visit the

but a sense of how much of that knowledge we lack. Our civilization has made its way from stone tools to robotaxis, mRNA vaccines, and LLM chatbots; we’d all be better able to inhabit it with even a slightly clearer idea of how it did so. Visit the