The history of birth control is almost as old as the history of the wheel.

Pessaries dating to Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt provide the launching pad for documentarian Lindsay Holiday’s overview of birth control throughout the ages and around the world.

Holiday’s History Tea Time series frequently delves into women’s history, and her pledge to donate a portion of the above video’s ad revenue to Pathfinder International serves as reminder that there are parts of the world where women still lack access to affordable, effective, and safe means of contraception.

One goal of the World Health Organization’s Ending Preventable Maternal Mortality initiative is for 65% of women to be able to make informed and empowered decisions regarding sexual relations, contraceptive use, and their reproductive health by 2025.

As Holiday points out, expense, social stigma, and religious edicts have impacted ease of access to birth control for centuries.

The further back you go, you can be certain that some methods advocated by midwives and medicine women have been lost to history, owing to unrecorded oral tradition and the sensitive nature of the information.

Holiday still manages to truffle up a fascinating array of practices and products that were thought — often erroneously — to ward off unwanted pregnancy.

Some that worked and continue to work to varying degrees, include barrier methods, condoms, and more recently the IUD and The Pill.

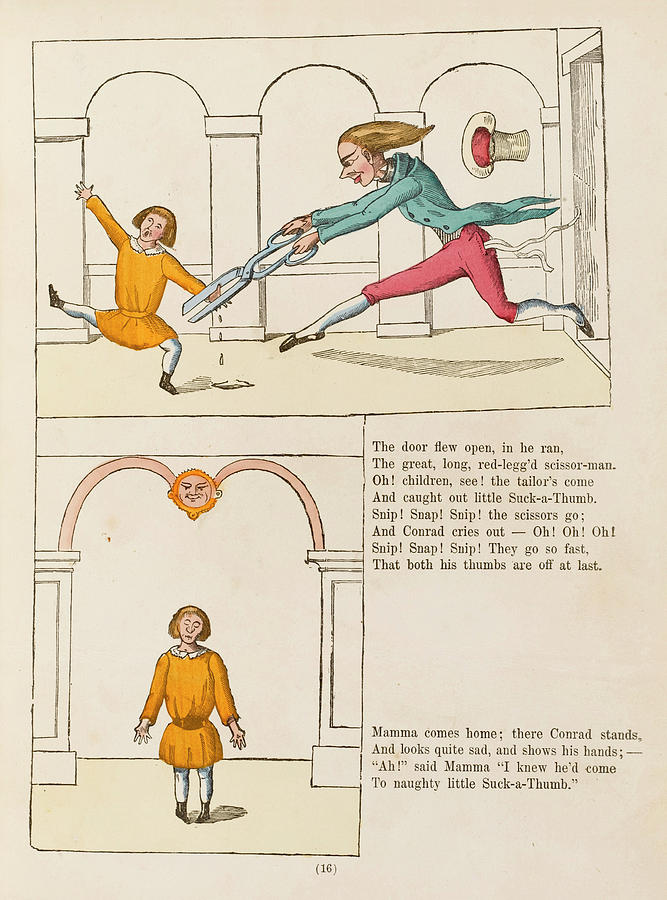

Definitely NOT recommended: withdrawal, holding your breath during intercourse, a post-coital sneezing regimen, douching with Lysol or Coca-Cola, toxic cocktails of lead, mercury or copper salt, anything involving alligator dung, and slugging back water that’s been used to wash a corpse.

As for silphium, an herb that likely did have some sort of spermicidal properties, we’ll never know for sure. By 1 CE, demand outstripped supply of this remedy, eventually wiping it off the face of the earth despite increasingly astronomical prices. Fun fact: silphium was also used to treat sore throat, snakebite, scorpion stings, mange, gout, quinsy, epilepsy, and anal warts

The history of birth control can be considered a semi-secret part of the history of prostitution, feminism, the military, obscenity laws, sex education and attitudes toward public health.

From Margaret Sanger and the 60,000 women executed as witches in the 16th and 17th centuries, to economist Thomas Malthus’ 1798 Essay on the Principle of Population and legendary adventurer Giacomo Casanova’s satin ribbon-trimmed jimmy hat, this episode of History Tea Time with Lindsay Holiday touches on it all.

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Related Content

The Story Of Menstruation: Watch Walt Disney’s Sex Ed Film from 1946