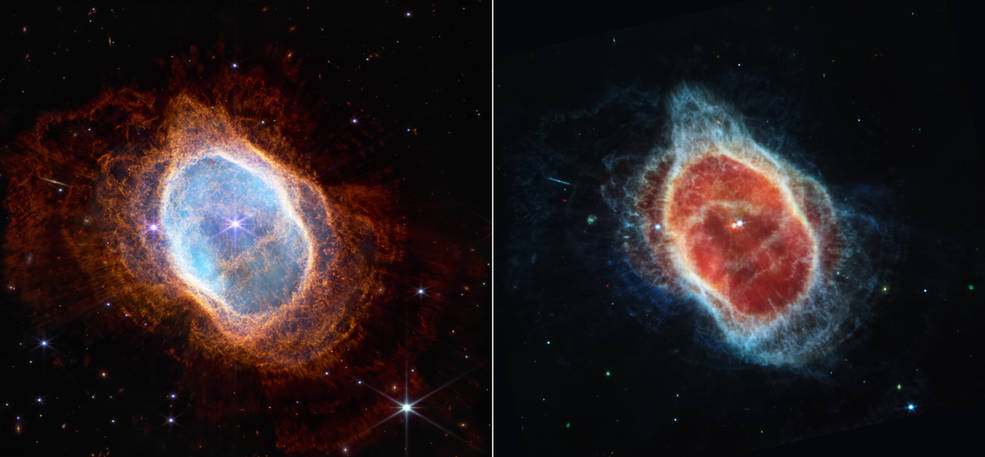

Late last year we featured the amazing engineering of the James Webb Space Telescope, which is now the largest optical telescope in space. Capable of registering phenomena older, more distant, and further off the visible spectrum than any previous device, it will no doubt show us a great many things we’ve never seen before. In fact, it’s already begun: earlier this week, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center released the first photographs taken through the Webb telescope, which “represent the first wave of full-color scientific images and spectra the observatory has gathered, and the official beginning of Webb’s general science operations.”

The areas of outer space depicted in unprecedented detail by these photos include the Carina Nebula (top), the Southern Ring Nebula (2nd image on this page), and the galaxy clusters known as Stephan’s Quintet (the home of the angels in It’s a Wonderful Life) and SMACS 0723 (bottom).

That last, notes Petapixel’s Jaron Schneider, “is the highest resolution photo of deep space that has ever been taken,” and the light it captures “has traveled for more than 13 billion years.” What this composite image shows us, as NASA explains, is SMACS 0723 “as it appeared 4.6 billion years ago” — and its “slice of the vast universe covers a patch of sky approximately the size of a grain of sand held at arm’s length by someone on the ground.”

All this can be a bit difficult to get one’s head around, at least if one is professionally involved with neither astronomy nor cosmology. But few imaginations could go un-captured by the richness of the images themselves. Sharp, rich in color, varied in texture — and in the case of the Carina Nebula or “Cosmic Cliffs,” NASA adds, “seemingly three-dimensional” — they could have come straight from a state-of-the-art science-fiction movie. In fact they outdo even the most advanced sci-fi visions, as NASA’s Earthrise outdid even the uncannily realistic-in-retrospect views of the Earth from space imagined by Stanley Kubrick and his collaborators in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

But these photos are the fruits of a real-life journey toward the final frontier, one you can follow in real time on NASA’s “Where Is Webb?” tracker. “Webb was designed to spend the next decade in space,” writes Colossal’s Grace Ebert. “However, a successful launch preserved substantial fuel, and NASA now anticipates a trove of insights about the universe for the next twenty years.” That’s quite a long run by the current standards of space exploration — but then, by the scale of space and time the Webb telescope has newly opened up, even 100 millennia is the blink of an eye.

Related content:

The Amazing Engineering of James Webb Telescope

How Scientists Colorize Those Beautiful Space Photos Taken By the Hubble Space Telescope

The Very First Picture of the Far Side of the Moon, Taken 60 Years Ago

The First Images and Video Footage from Outer Space, 1946–1959

The Beauty of Space Photography

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.