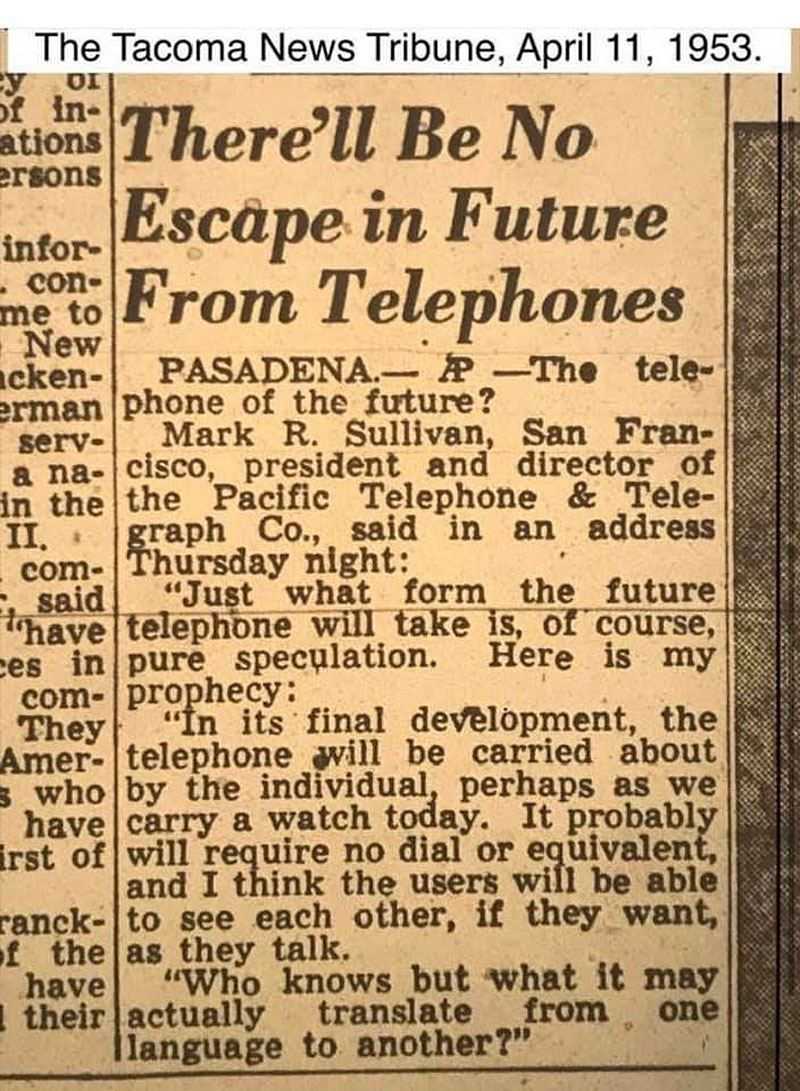

We live in the age of the smartphone, which took more than a few of us by surprise. But in all human history, not a single piece of technology has actually come out of nowhere. Long before smartphones came on the market in the 2000s, those close to the telecommunications industry had a sense of what form its most widely used device would eventually take. “Here is my prophecy: In its final development, the telephone will be carried about by the individual, perhaps as we carry a watch today,” said Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Company director Mark R. Sullivan in 1953. “It probably will require no dial or equivalent and I think the users will be able to see each other, if they want, as they talk. Who knows but it may actually translate from one language to another?”

Sullivan’s prescient-sounding words survive in the clipping of the Associated Press article seen at the top of the post. It’s worth remembering that the speech in question dates from a time when the rotary phone was the most advanced personal communication device in American households.

Just three years earlier, writes KQED’s Rae Alexandra, Sullivan “appeared in the San Francisco Examiner talking about the latest innovations in telephone technology. The advancement he was most proud of was a new device about the size of a small typewriter that automatically calculated how long people’s phone calls were.” However logical, pocket telephones with video-calling and translation capabilities would then have struck many as the stuff of science fiction.

Though born before the time of household electrification, Sullivan himself lived just long enough to see the debut of the first commercial cellphone “The Motorola DynaTAC 8000X was definitely not watch-sized and cost a whopping $3,995 in 1983 (about $11,000 today),” writes Alexandra, “but Sullivan might have seen this development as a step towards his long-ago vision — a sign that every one of his 1953 predictions would eventually come to fruition.” As printed in the Tacoma News Tribune, the AP article conveying those predictions to the public appeared under the headline “There’ll Be No Escape in Future from Telephones,” which sounds even more chilling today — in that very future — than it did nearly 70 years ago. But then, even the visions of actual science fiction are seldom wholly untroubled.

Related Content:

A 1947 French Film Accurately Predicted Our 21st-Century Addiction to Smartphones

When We All Have Pocket Telephones (1923)

Filmmaker Wim Wenders Explains How Mobile Phones Have Killed Photography

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.