Few jazz guitarists today could claim to be entirely free of the influence of Django Reinhardt. This despite the fact that he lost the use of two fingers — which ultimately encouraged him to develop a distinctive playing style — and that he died 68 years ago. The unfortunate abbreviation of Reinhardt’s life means that he never built a substantial body of solo work, though he did play on many recorded dates that include performances alongside Coleman Hawkins and Benny Carter. It also means that he left even less in the way of footage, though we do get a crisp and illuminating view of him and his guitar in the 1938 documentary short “Jazz ‘Hot,’ ” previously featured here on Open Culture.

“Jazz ‘Hot’ ” also features violin-playing from Stéphane Grappelli, who founded the group Quintette du Hot Club de France with Reinhardt in 1934. As they deepened their knowledge of jazz, the two influenced each other so thoroughly as to develop their own style of music.

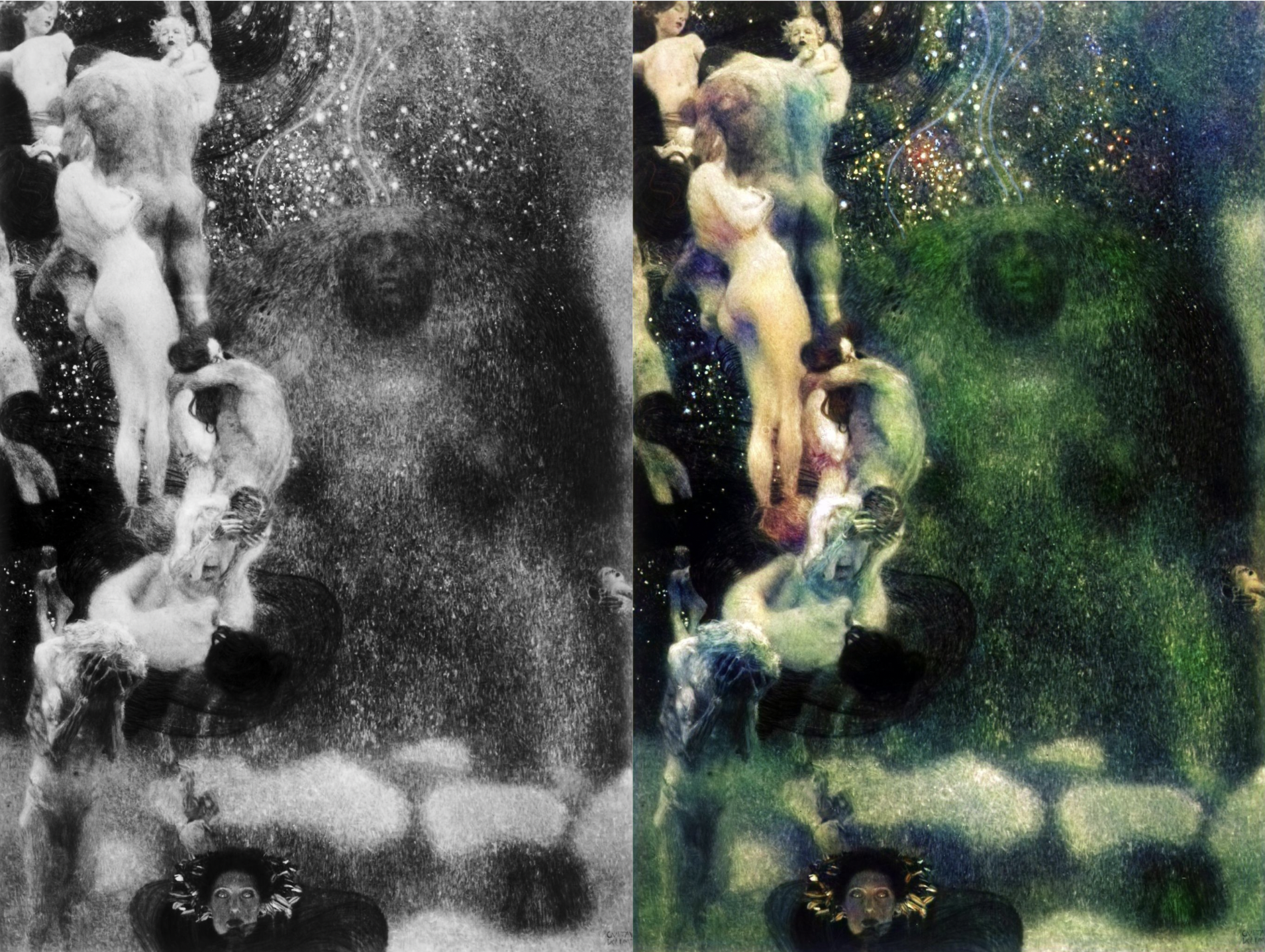

Grappelli lived long enough to play with the likes of Jean-Luc Ponty, Paul Simon, Yo Yo Ma, and even Pink Floyd. Still, more than a few jazz fans would surely claim that none of his professional collaborators was more important to his musical formation than Reinhardt. Now you can see them playing together in color, and fairly realistic color at that, in the clip at the top of the post.

The original black-and-white footage (which appears just above) was colorized with DeOldify, a deep learning-based application developed to restore photographs and motion pictures from bygone times. Perhaps you’ve seen the previous DeOldify colorization projects we’ve featured here, which run the gamut from musical numbers in Stormy Weather and Hellzapoppin’ to scenes of 1920s Berlin and even an 1896 snowball fight in Lyon. Granted access to a time machine, more than a few jazz-lovers would no doubt choose to go back to the Paris of the 1930s to see the Quintette du Hot Club de France in action. Technology has yet to make that a viable proposition, but it’s given us a next-best-thing that no appreciator of jazz guitar — or jazz violin — could fail to enjoy.

Related Content:

Jazz ‘Hot’: The Rare 1938 Short Film With Jazz Legend Django Reinhardt

Django Reinhardt Demonstrates His Guitar Genius in Rare Footage From the 1930s, 40s & 50s

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.