Whatever your feelings about the sentimental, lighthearted 1960 Disney film Pollyanna, or the 1913 novel on which it’s based, it’s fair to say that history has pronounced its own judgment, turning the name Pollyanna into a slur against excessive optimism, an epithet reserved for adults who display the guileless, out-of-touch naïveté of children. Pitted against Pollyanna’s effervescence is Aunt Polly, too caught up in her grown-up concerns to recognize, until it’s almost too late, that maybe it’s okay to be happy.

Maybe we all have to be a little like practical Aunt Polly, but do we also have a place for Pollyannas? Can that not also be the role of the modern artist? David Byrne hasn’t been waiting for permission to spread joy in his late career. Contra the common wisdom of most adults, a couple years back Byrne began to gather positive news stories under the heading Reasons to Be Cheerful, now an online magazine.

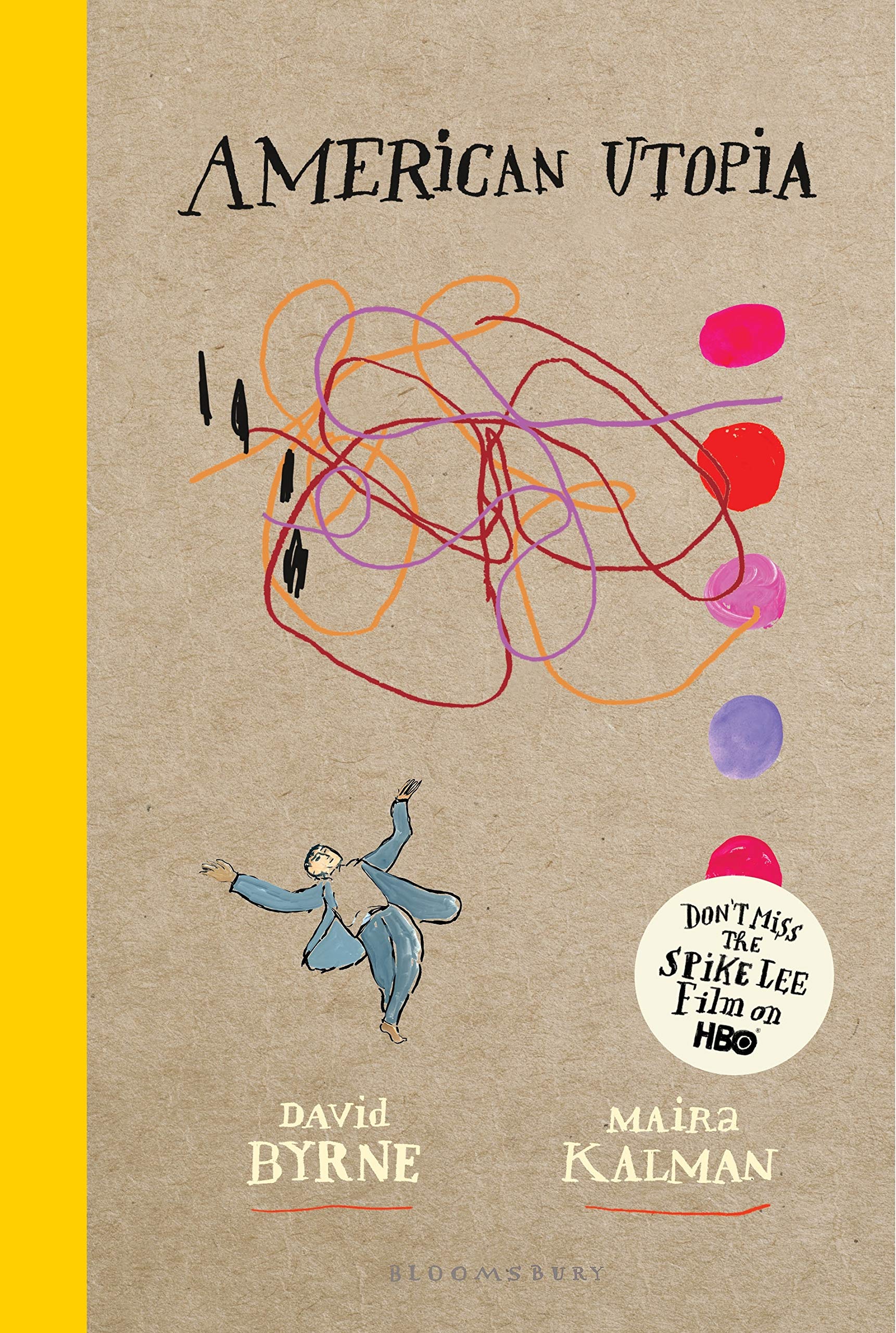

Then, Byrne had the audacity to call a 2018 album, tour, and Broadway show American Utopia, and the gall to have Spike Lee direct a concert film with the same title, and release it smack in the middle of 2020, a year all of us will be glad to see in hindsight. Byrne’s two-year endeavor can be seen as his answer to “American Carnage,” the grim phrase that began the Trump era.

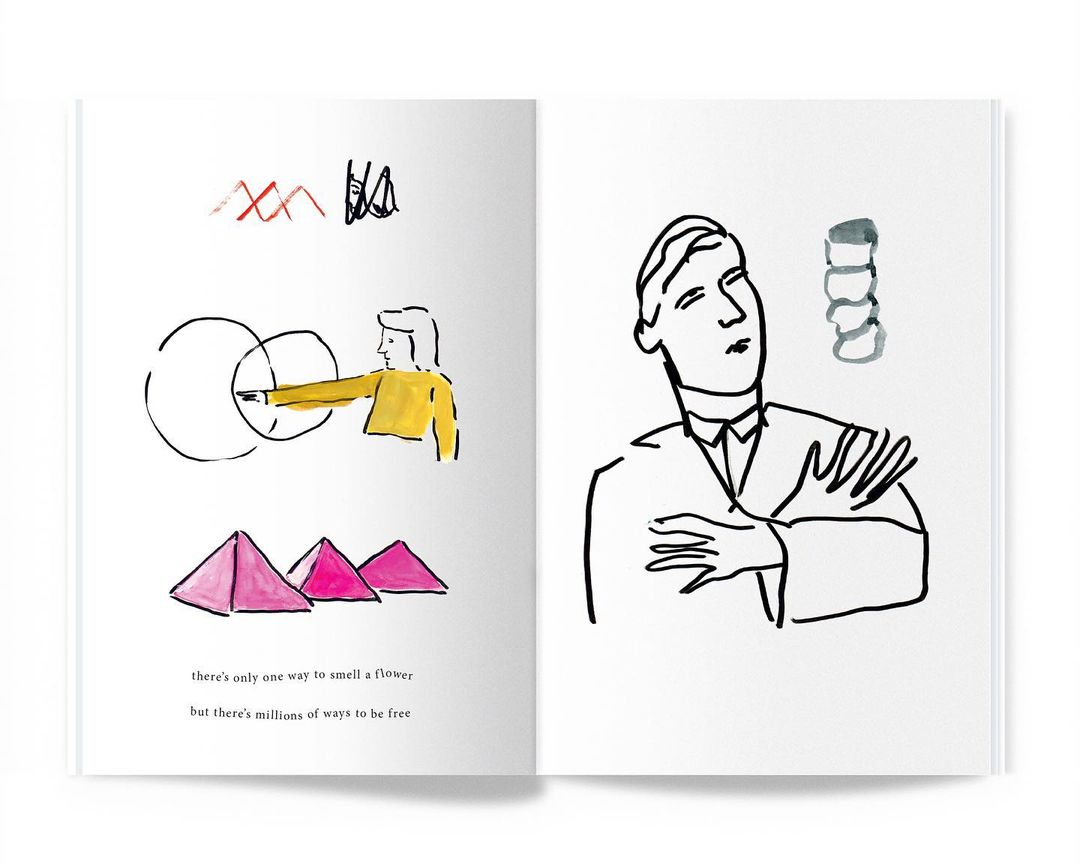

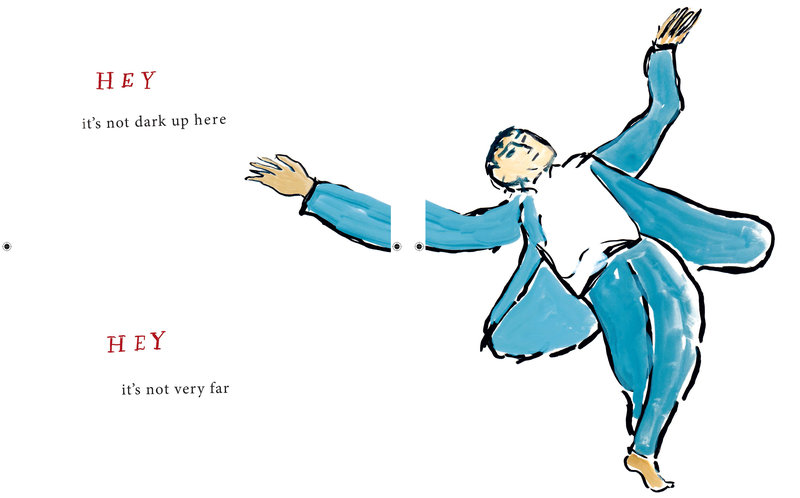

As if all that weren’t enough, American Utopia is now an “impressionistic, sweetly illustrated adult picture book,” as Lily Meyer writes at NPR, “a soothing and uplifting, if somewhat nebulous, experience of art.” Working with artist Maira Kalman, Byrne has turned his conceptual musical into something like a “book-length poem… filled with charming illustrations of trees, dancers, and party-hatted dogs.”

Byrne’s project is not naive, Maria Popova argues at Brain Pickings, it’s Whitmanesque, a salvo of irrepressible optimism against “a kind of pessimistic ahistorical amnesia” in which we “judge the deficiencies of the present without the long victory ledger of past and fall into despair.” American Utopia doesn’t articulate this so much as perform it, either with bare feet and gray suits onstage or the vivid colors of Kalman’s drawings, “lightly at odds,” Meyer notes, “with Byrne’s words, transforming their plain optimism into a more nuanced appeal.”

American Utopia the book, like the musical before it, was written and drawn before the pandemic. Do Byrne and Kalman still have reasons to be cheerful post-COVID? Just last week, they sat down with Isaac Fitzgerald for Live Talks LA to discuss it. You can see the whole, hour-long conversation just above. Kalman confesses she’s still in “quiet shock,” but finds hope in historical perspective and “incredible people out there doing fantastic things.”

Byrne takes us on one of his fascinating investigations into the history of thought, referencing a theorist named Aby Warburg who saw in the sum total of art a kind “animated life” that connects us, past, present, and future, and who reminded him, “Yes, there are other ways of thinking about things!” Perhaps the visionary and the Pollyannaish need not be so far apart. See several more of Kalman and Byrne’s beautifully optimistic pages from American Utopia, the book, at Brain Pickings.

Related Content:

David Byrne’s American Utopia: A Sneak Preview of Spike Lee’s New Concert Film

Watch Life-Affirming Performances from David Byrne’s New Broadway Musical American Utopia

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness