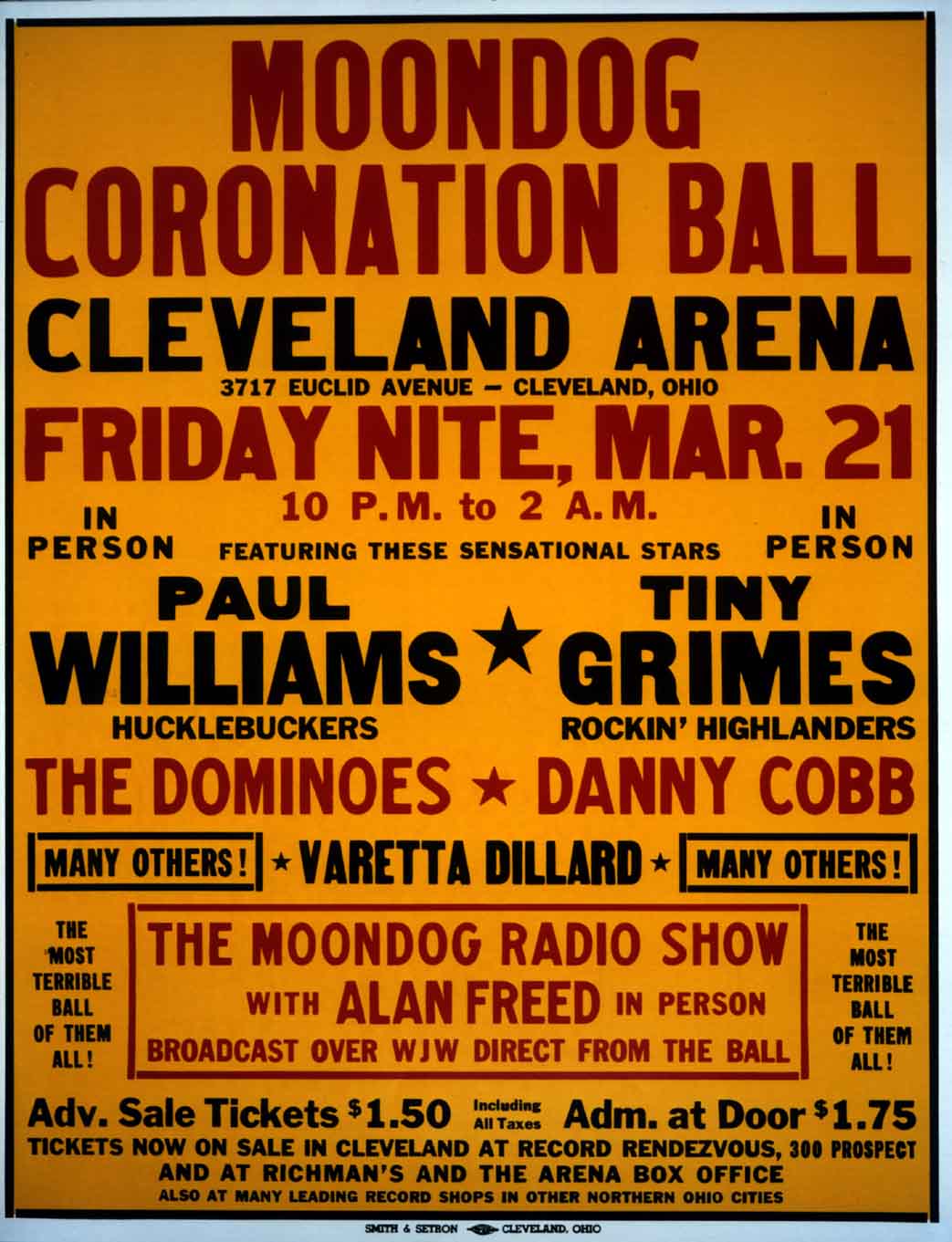

Standing atop the Acropolis in Athens as it has for nearly 2,500 years now, the Parthenon remains an impressive sight indeed. Not that those two and a half millennia have been kind to the place: one of the most famous ruins of the ancient world is still, after all, a ruin. But it does fire up visitors’ imaginations, filling their heads with visions of how it must have looked back in the fifth century BC, when it was a functioning temple and treasury. One enthusiast in particular, an Oxford archaeology professor named Juan de Lara, has spent four years using 3D modeling tools to create a 3D digital reconstruction of the Parthenon at the height of its glory, of which you can get glimpses in the video above and at the project’s official site.

Image by Juan de Lara/The Parthenon 3D

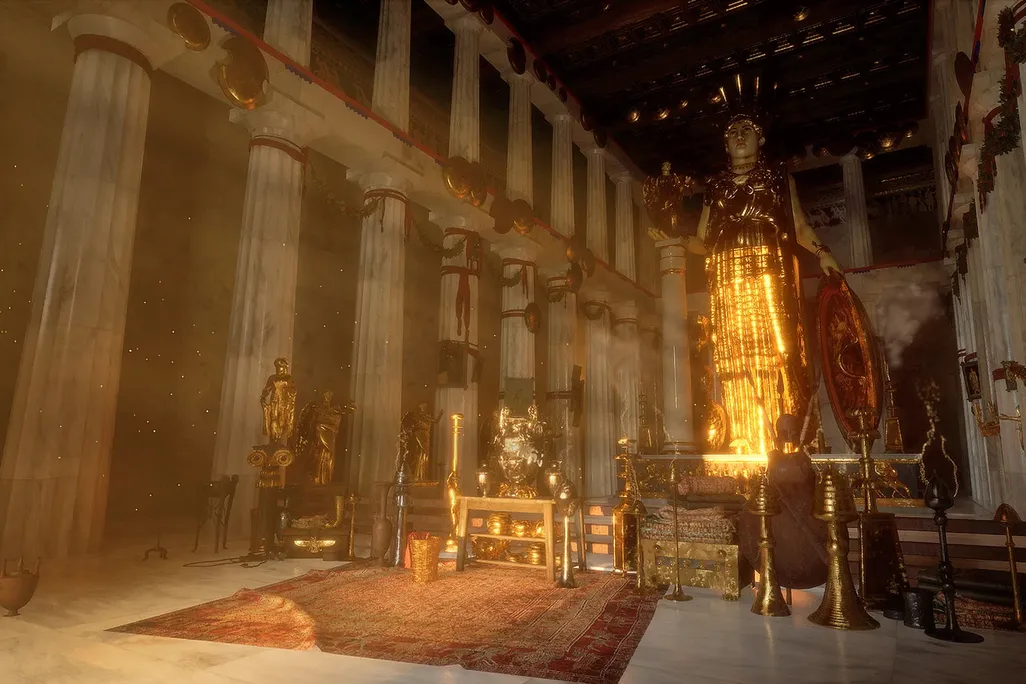

The materials promoting Parthenon 3D, as it’s called, emphasize one element above all: its almost 40-foot-tall statue of the goddess Athena Parthenos, better known mononymically as Athena. The work of the renowned sculptor Phidias, who also handled the rest of the structure’s sculptural decoration, it ended up costing twice as much as the building itself.

Though now long lost, the Athena statue was well documented enough for de Lara to model its every detail, down to the folds in her golden robes and the cracks in her ivory skin. During the Panathenaic Festival, which came around every four years, sunlight would enter the Parthenon at just the right angle to cause a supernatural-looking illumination of the goddess against the surrounding darkness.

Image by Juan de Lara/The Parthenon 3D

Of course, that effect wasn’t accidental. Even if we consider the creation of the Parthenon to have been divinely inspired, we can best understand it as a work of man — and a meticulously thought-out work at that. For ancient Greek visitors, the illumination of Athena would have been enhanced by the placement of roof apertures, reflecting water pools, and reflective materials, whose original incorporation into the space would come as a surprise to most modern visitors. At present, Parthenon 3D offers the closest experience we have to a time machine set to the Parthenon as Phidias and architects Iktinos and Callicrates originally intended. But as de Lara’s research notes, the building also contained numerous incense burners, so perfect realism won’t be achieved until smells can go through the internet. Visit the Parthenon 3D site here.

Image by Juan de Lara/The Parthenon 3D

Related content:

How the Parthenon Marbles Ended Up In The British Museum

A Virtual Tour of Ancient Athens: Fly Over Classical Greek Civilization in All Its Glory

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.