Difficult as it may be to remember now, there was a time when Meryl Streep was not yet synonymous with silver-screen stardom — a time, in fact, when she had yet to appear on the silver screen at all. Half a century ago, she was just another young stage actress in New York, albeit one rapidly ascending the rungs of theatrical prestige, doing three Shakespeare plays and then starring in Weill, Hauptmann, and Brecht’s Happy End on Broadway. The Deer Hunter, Kramer vs. Kramer, Out of Africa, Postcards from the Edge, The Bridges of Madison County: all this lay in her future in 1976, the year of her feature debut.

Streep made that debut in Everybody Rides the Carousel, a now-obscure animated film that dramatizes post-Freudian psychologist Erik Erikson’s eight stages of psychosocial development. First published in his book Childhood and Society in 1950, this scheme captured the imagination of the mid-century American public, growing ever hungrier as it was for clear, legible systems of self-understanding.

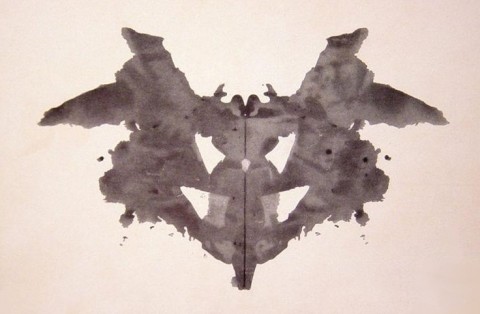

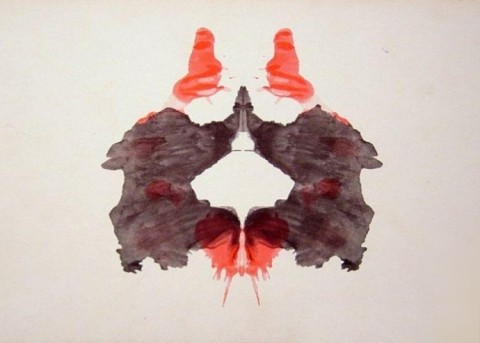

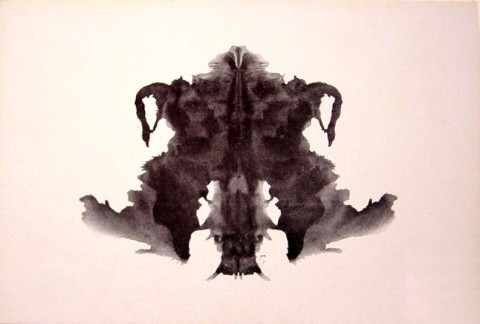

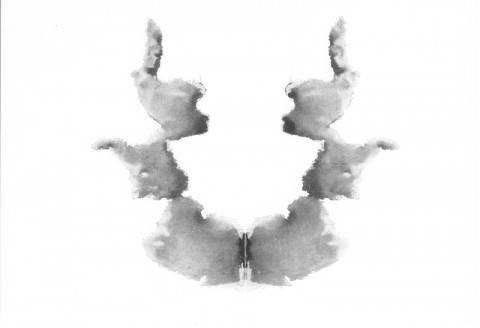

Erikson conceived of each age of man as a struggle for resolution between two opposing forces: in infancy, for example, trust versus mistrust; in adolescence, identity versus role confusion; and so on.

The young Meryl Streep, or rather her voice, appears in the sixth stage, early adulthood, whose theme is love. She acts out that age’s contest of intimacy and isolation with Charles Levin, another up-and-comer who would go on to achieve wide recognition on television shows like Alice, Hill Street Blues, and (just once, but memorably) Seinfeld. In character as a young couple unsteadily feeling their way through their relationship, the two engage in a remarkably naturalistic conversation, all animated in a seventies watercolor style in the vision of director John Hubley. A prolific animator who’d worked on Disney’s Fantasia, Hubley was known as the creator of Mr. Magoo: a man who provided us all with an example of how to navigate late adulthood’s path between ego integrity and despair, however myopically.

via Messy Nessy

Related content:

Watch Meryl Streep Have Fun with Accents: Bronx, Polish, Irish, Australian, Yiddish & More

Master of Light: A Close Look at the Paintings of Johannes Vermeer Narrated by Meryl Streep

Marcel Marceau Mimes the Progression of Human Life, From Birth to Death, in 4 Minutes

Meryl Streep Gives Graduation Speech at Barnard

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.