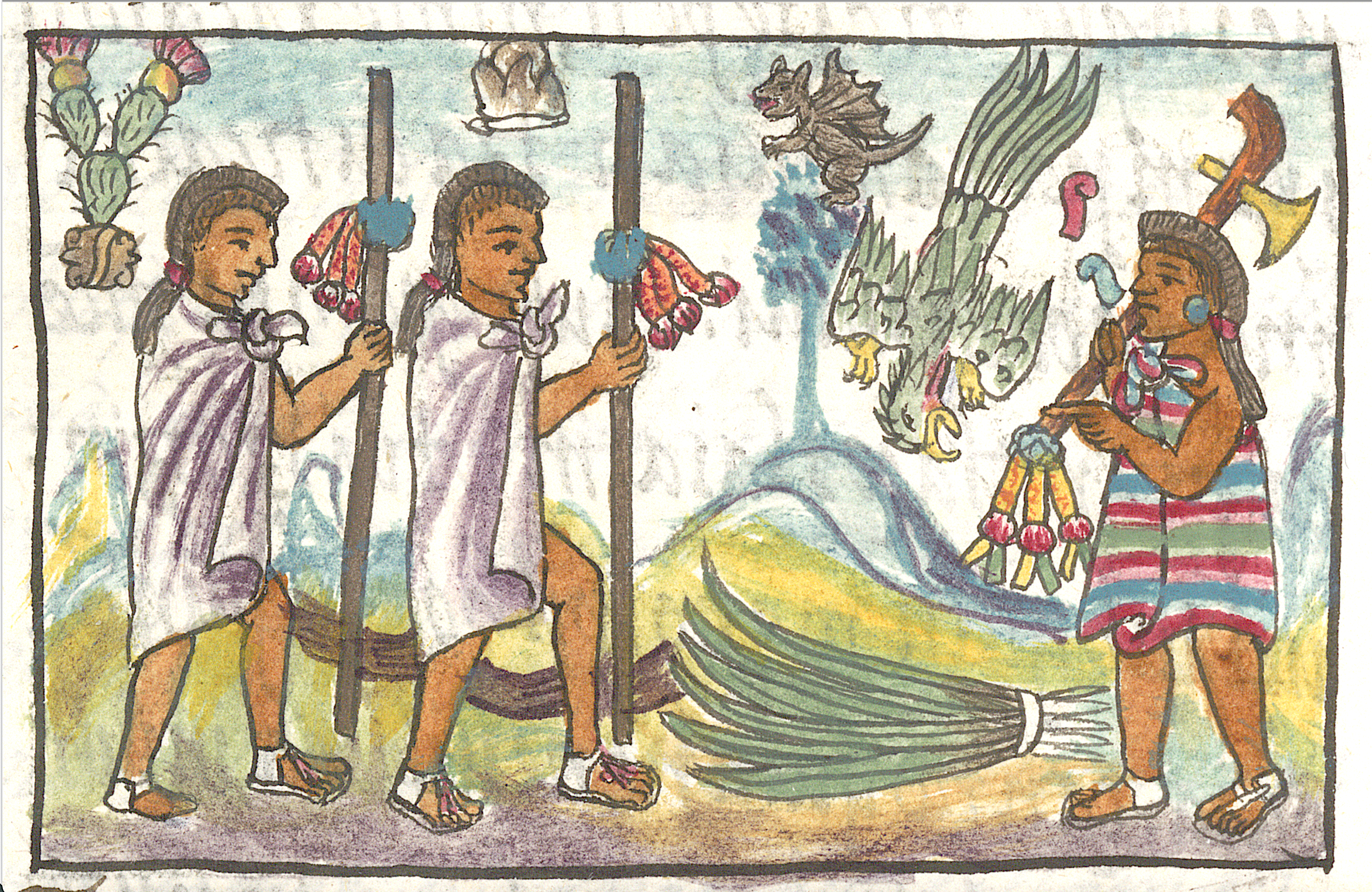

The Spanish conquista of the Americas happened long enough ago — and left behind a spotty enough body of historical records — that we tend to perceive it as much through simplifications, exaggerations, and distortions as we do through facts. What we now call Mexico underwent “essentially an internal conflict between different indigenous groups who saw the arrival of strangers as an opportunity to resist having to pay tribute to the Aztec Empire,” says Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico history professor Berenice Alcántara Rojas. “When the Spaniards initially attacked the Mexica capital, they were swiftly driven out.”

“Only when aided by various groups of Indigenous allies, as well as by the spread of a terrible smallpox epidemic, did they manage to force the ruler Cuauhtemoc and other Mexica leaders to capitulate,” Rojas continues, drawing upon details provided in the version of the events laid out in the Florentine Codex.

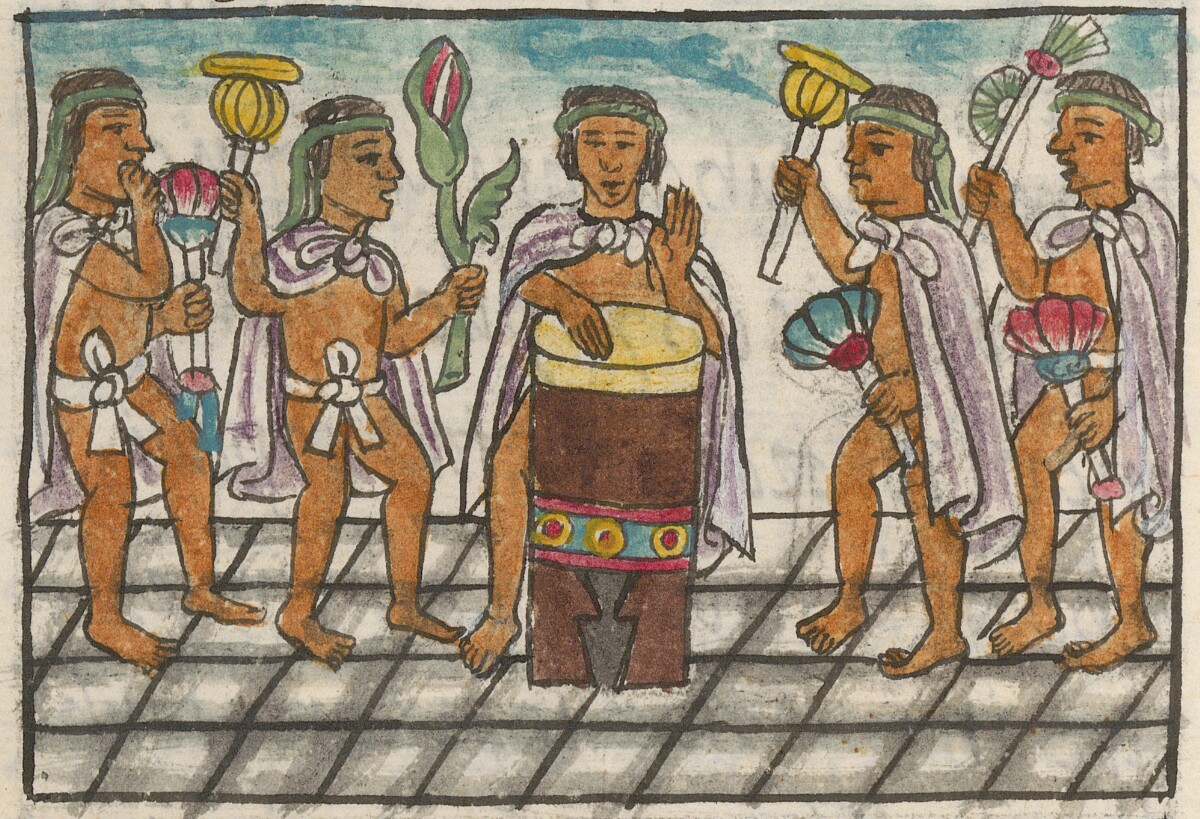

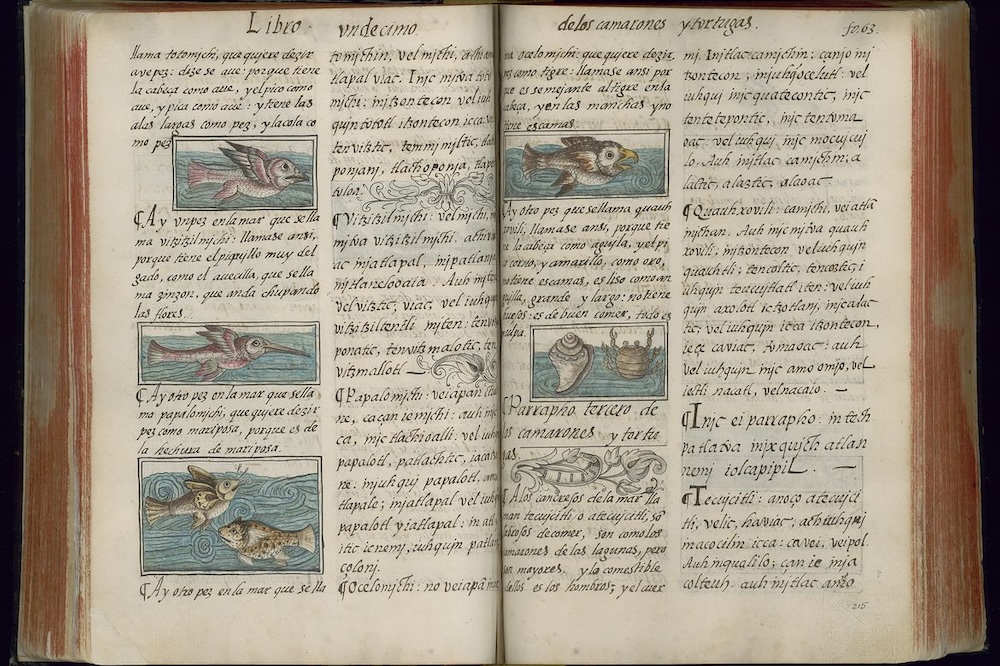

That encyclopedic series of twelve 16th-century illustrated manuscripts lavishly documents the known society and nature of that land at the time — and has now, nearly 450 years later, been acknowledged as “the most reliable source of information about Mexica culture, the Aztec Empire, and the conquest of Mexico.”

“In 1547, Bernardino de Sahagún, a Spanish Franciscan friar who committed most of his life to working closely with the Indigenous peoples of Mexico, began collecting information about central Mexican Nahua culture, life, people, history, astronomy, flora, fauna, and the Nahuatl language, among other topics,” says the Getty Research Institute. “Nahua elders, grammarians, scribes, and artists worked with Sahagún to compile a three-volume, 12-book, 2500-page illustrated manuscript, modeling its content on European encyclopedias, especially Pliny the Elder’s Natural History,” all of which has been digitized, translated, and made available at the Getty’s web site.

A thoroughly multicultural project avant la lettre, the Florentine Codex (named for the Medici family library in Florence, where it was sent upon its completion) has only just become accessible to a wide online readership. Though it’s “been digitally available via the World Digital Library since 2012, for most users it remained impenetrable because reading it requires knowledge of sixteenth-century Nahuatl and Spanish, and of pre-Hispanic and early modern European art traditions.” By offering searchable text in modern versions of both those languages as well as English — to say nothing of its browsable sections organized by people, animals, deities, and even by Nahuatl terms like coyote and tortilla — the Digital Florentine Codex re-illuminates an entire civilization.

Related content:

Native Lands: An Interactive Map Reveals the Indigenous Lands on Which Modern Nations Were Built

Explore the Codex Zouche-Nuttall: A Rare, Accordion-Folded Pre-Columbian Manuscript

How the Ancient Mayans Used Chocolate as Money

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.