The 10 Paradoxical Traits of Creative People, According to Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (RIP)

Despite decades of research, scientists still know little about the source of creativity. Nonetheless, humans continue to create things. Or, at least, we continue to be fascinated by creativity; now more than ever, it seems. There may be as many best-selling books on creativity as there are on dieting or relationships. The current focus on creativity isn’t always a net positive. Anyone who does creative work may be labeled a “Creative” (used as a noun) at some point in their career. The term lumps all working artists together, as though their work were interchangeable deliverables measured in billable hours. The word suggests that those who don’t work as “Creatives” have no business in the area of creativity. As psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi put it:

Not so long ago, it was acceptable to be an amateur poet…. Nowadays if one does not make some money (however pitifully little) out of writing, it’s considered to be a waste of time. It is taken as downright shameful for a man past twenty to indulge in versification unless he receives a check to show for it.

Csikszentmihalyi, who passed away this month, deplored the instrumentalization of creativity. He wrote, Austin Kleon notes, “about the joys of being an amateur” — which, in its literal sense, means being a devoted lover. Like Carl Jung, Csikszentmihalyi believed that creation proceeds, in a sense, from falling in love with an activity and losing ourselves in a state beyond our preoccupations with self, others, or the past and future. He called this state “flow” and wrote a national bestseller about it while founding the discipline of positive psychology and co-directing the Quality of Life Research Center at Claremont Graduate University .

You can see an animated summary of Csikszentmihalyi’s book, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience above (including a pronunciation of Csikszentmihalyi’s name). Creativity should not only refer to skills we sell to our employers. It is the practice of doing things that make us happy, not the things that make us money, whether or not those two things are the same. This is a subject close to Austin Kleon’s heart. The writer and designer has been offering tips for training and honing creativity for years, in books like Show Your Work, a guide “not just for ‘creatives’!” but for anyone who wants to create. Like Csikszentmihalyi, he refutes the idea that there’s such a thing as a “creative type.”

Instead, in his book Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention, Csikszentmihalyi notes that people who spend their time creating exhibit a list of 10 “paradoxical traits.”

- Creative people have a great deal of physical energy, but they’re also often quiet and at rest.

- Creative people tend to be smart yet naive at the same time.

- Creative people combine playfulness and discipline, or responsibility and irresponsibility.

- Creative people alternate between imagination and fantasy, and a rooted sense of reality.

- Creative people tend to be both extroverted and introverted.

- Creative people are humble and proud at the same time.

- Creative people, to an extent, escape rigid gender role stereotyping.

- Creative people are both rebellious and conservative.

- Most creative people are very passionate about their work, yet they can be extremely objective about it as well.

- Creative people’s openness and sensitivity often exposes them to suffering and pain, yet also to a great deal of enjoyment.

We may well be reminded of Walt Whitman’s “Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself,” and perhaps it is to Whitman we should turn to resolve the paradox. Creativity involves the willingness and courage to become “large,” the poet wrote, to get weird and messy and “contain multitudes.” Maybe the best way to become a more creative person, to lose oneself fully in the act of making, is to heed Bertrand Russell’s guidance for facing death:

[M]ake your interests gradually wider and more impersonal, until bit by bit the walls of the ego recede, and your life becomes increasingly merged in the universal life. An individual human existence should be like a river: small at first, narrowly contained within its banks, and rushing passionately past rocks and over waterfalls. Gradually the river grows wider, the banks recede, the waters flow more quietly, and in the end, without any visible break, they become merged in the sea…

This eloquent passage — Csikszentmihalyi might have agreed — expresses the very essence of creative “flow.”

via Austin Kleon

Related Content:

Slavoj Žižek: What Fullfils You Creatively Isn’t What Makes You Happy

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...How Randy Bachman Found His Stolen Favorite Guitar After 45 Years, with the Help of Facial-Recognition Software

Facial-recognition technology has come into its own in recent decades, though its imagined large-scale uses do tend to sound troublingly dystopian. Still, some of its actual success stories have been pleasing indeed, few of them so much as the one briefly told in the video above by Bachman Turner Overdrive’s Randy Bachman. Its protagonist is not Bachman himself but one of his guitars: a 1957 Gretsch 6120 Chet Atkins, a model named after the star Nashville guitarist. “This is the first really good expensive electric guitar I got,” he says, adding that he “played it on many, many BTO hits, and in 1975 it was stolen from a Holiday Inn hotel room in Toronto.”

“The disappearance triggered a decades-long search,” writes Todd Coyne in a feature at CTV News. “Bachman enlisted the help of the RCMP” — also known at the Mounties — “the Ontario Provincial Police and vintage instrument dealers across Canada and the United States. It also triggered what Bachman now recognizes as a mid-life crisis,” resulting in his eventual purchase of 385 Gretsch guitars. Those included a dozen 6120s from the 1950s, but none of them were the one he bought at age 20 from Winnipeg Piano. He must have given up hope by the time the message arrived: “I found your Gretsch guitar in Tokyo.”

The sender, an old neighbor of Bachman’s, had in fact found the Gretsch on Youtube. In the video below, made for Christmas 2019, a Japanese guitarist named Takeshi plays “Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree” on an orange 6120 that Bachman immediately recognized as his long-lost favorite instrument. Coyne writes that the neighbor “had used some old photographs of the guitar and rejigged some facial-recognition software to identify and detect the unique wood-grain patterns and lines of cracked lacquer along the instrument’s body,” as seen in the original video for BTO’s “Lookin’ Out for #1.” Subsequently, he “ran scans of this unique profile against every image he could find of an orange 1957 Chet Atkins guitar posted online over the last decade and a half.”

Persistence, at least in this case, paid off. But since Takeshi felt nearly as strong a connection to the guitar as Bachman did, an arrangement had to be made. With the Japanese wife of his son Tal (also a musician, best known for the 1990s hit “She’s So High”) acting as interpreter, he negotiated with Takeshi the terms of an exchange. As Bachman tells it, “He said he would give me back my guitar, but I had to find him its twin”: the same model — of which only 35 were made in 1957 — in mint condition with all the same parts and no additional modifications. And for a mere thirty times the $400 price he originally paid, he eventually found that twin. Now all that remains, as soon travel restrictions ease between the U.S. and Japan, is for Bachman and Takeshi to meet up at the Gretsch factory in Nagoya, play a gig together, and take care of business.

Related Content:

Guitarist Randy Bachman Demystifies the Opening Chord of The Beatles’ “A Hard Day’s Night”

Guitar Stories: Mark Knopfler on the Six Guitars That Shaped His Career

The Captivating Art of Restoring Vintage Guitars

Hear Joni Mitchell’s Earliest Recording, Rediscovered After More than 50 Years

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

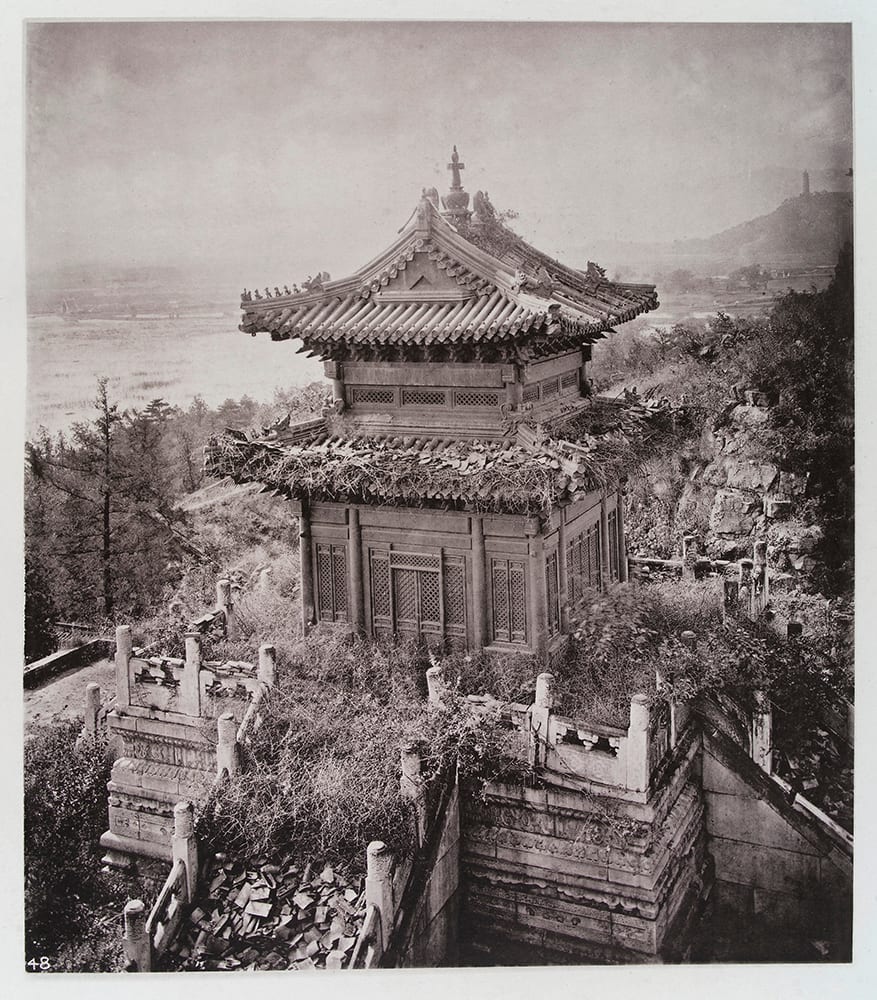

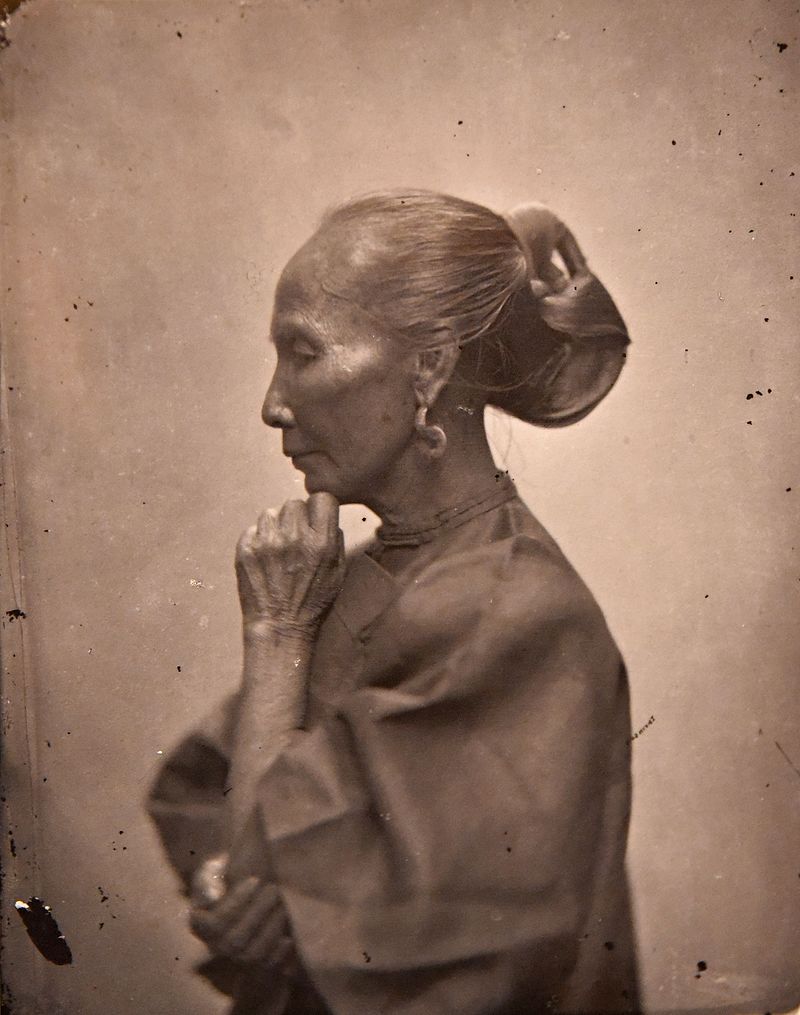

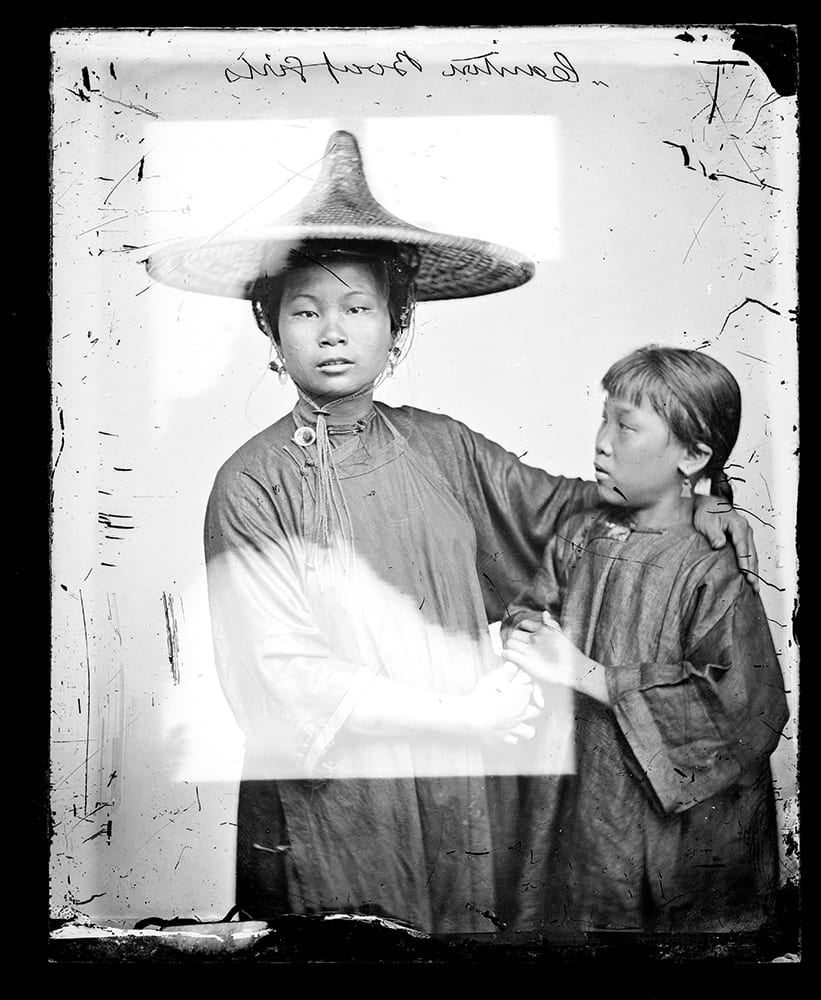

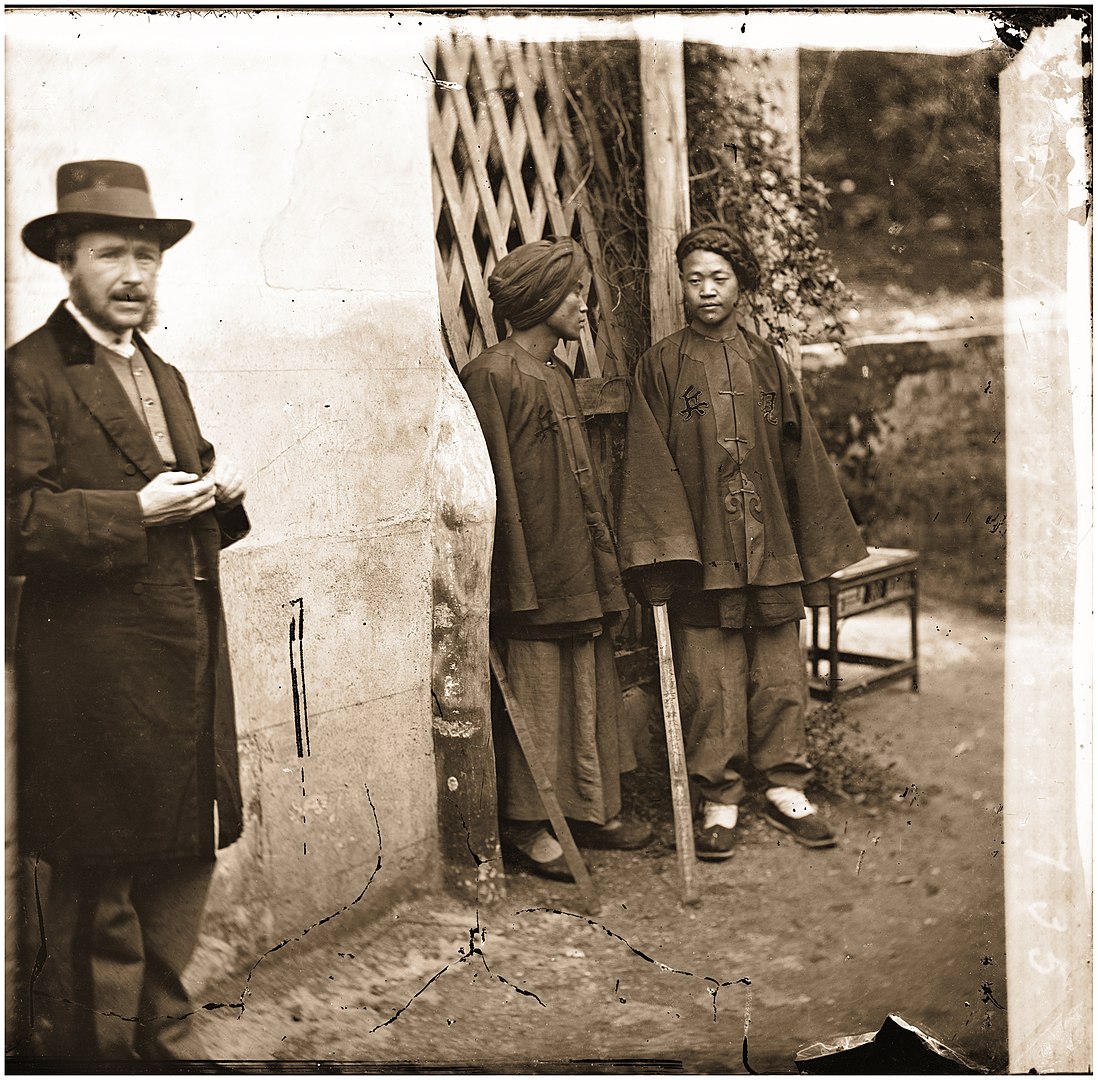

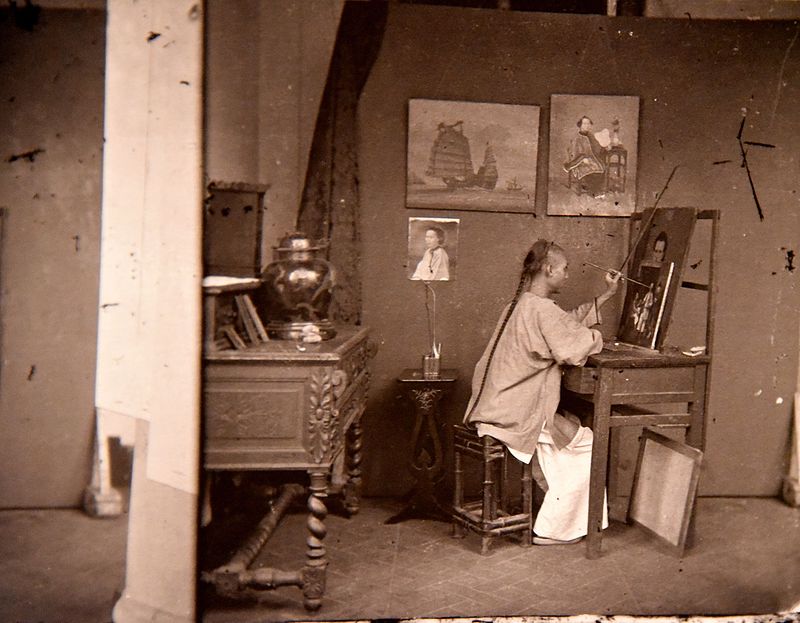

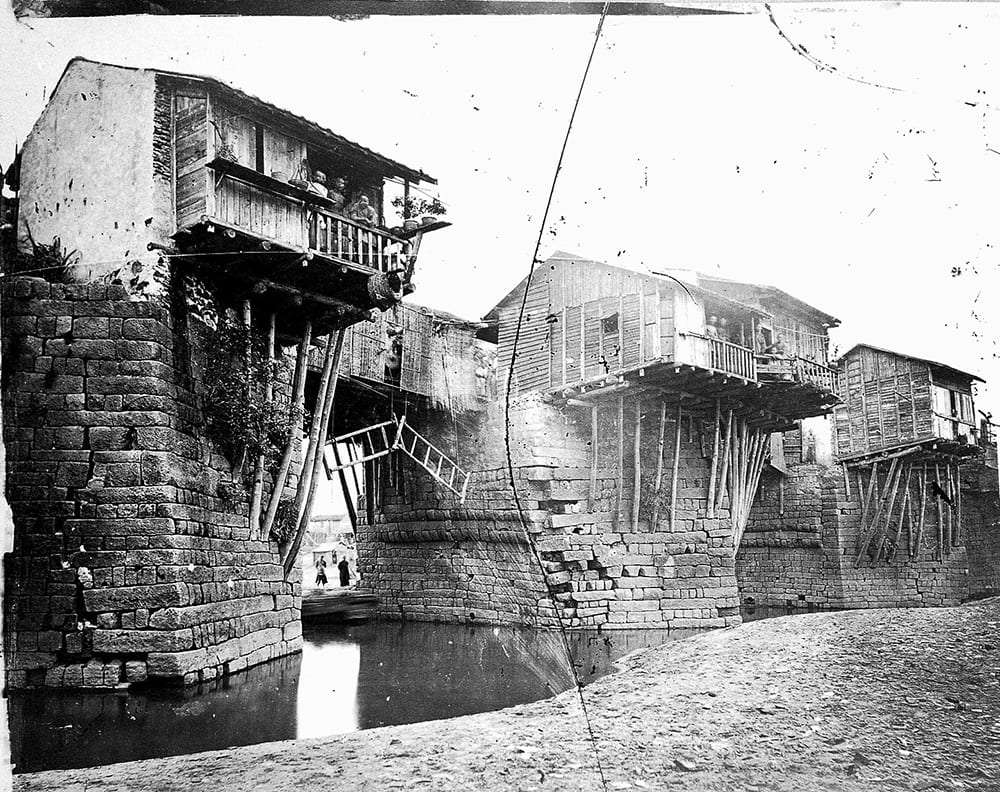

Read More...Behold the Photographs of John Thomson, the First Western Photographer to Travel Widely Through China (1870s)

In the early 1860s, a few Westerners had seen China — but nearly all of them had seen it for themselves. The still-new medium of photography had yet to make images of everywhere available to viewers everywhere else, which meant an opportunity for traveling practitioners like John Thomson. “The son of a tobacco spinner and shopkeeper,” says BBC.com, ” he was apprenticed to an Edinburgh optical and scientific instrument manufacturer where he learned the basics of photography.”

In 1862 Thomson sailed from Leith “with a camera and a portable dark room. He set up in Singapore before exploring the ancient civilizations of China, Thailand — then known as Siam — and Cambodia.” It is for his extensive photography of China in the late 1860s and early 1870s that he’s best known today.

First lavishly published in a series of books titled Illustrations of China and Its People (now available to read free online at the Yale University Library: volume one, volume two, volume three, volume four), they now constitute some of the earliest and richest direct visual records of Chinese landscapes, cityscapes, and society as they were in the late 19th century.

“The first Western photographer to travel widely through the length and breadth of China,” Thomson brought his camera on journeys “far more extensive than those undertaken by most Westerners of his generation,” extending “beyond the relative comfort and safety of the coastal treaty ports.” Those words come from scholar of the 19th-century Allen Hockley, whose five-part visual essay “John Thomson’s China” at MIT Visualizing Cultures provides a detailed overview and historical contextualization of Thomson’s work in Asia.

Thomson’s photographs, writes Hockley, “fall into two broad categories: scenic views and types. Views encompassed both natural landscapes and built environments. They could be panoramic, taking in large swaths of scenery, or they might highlight specific natural phenomena or individual structures.”

Types “focused on the manners and customs of Chinese people and tended to highlight the defining features of gender, age, class, ethnicity, and occupation.” A century and a half later, both Thomson’s views and types have given scholars in a variety of disciplines much to discuss.

“It is clear from his commentary to Illustrations of China that, however sympathetic he was towards Chinese people, he could often be superior and high-handed,” writes Andrew Hiller at Visualizing China. “If Thomson never sought to question the validity of Britain’s presence, his attitude towards China was ambivalent. Whilst critical of what he saw as the corruption and obfuscation of Qing officials, he nevertheless could see the country’s potential.”

Thomson also helped others to see that potential — or at least those who could afford to buy his books, whose prices matched the quality of their production. But today, thanks to online archives like Historical Photographs of China and Wellcome Collection, they’re free for everyone to behold. China itself has become much more accessible since Thomson’s day, of course, but it’s famously a much different place than it was 25 years ago, let alone 150 years ago. The land through which he traveled — and of which he took so many of the very earliest photographs — is now infinitely less accessible to us than it ever was to his fellow Westerners of the 19th century.

Hear a lecture on Thomson’s photography in China from the University of London here.

Related Content:

How Vividly Colorized Photos Helped Introduce Japan to the World in the 19th Century

1850s Japan Comes to Life in 3D, Color Photos: See the Stereoscopic Photography of T. Enami

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...How Victorian Homes Turned Deadly: Exploding Stoves, Poison Wallpaper, Ever-Tighter Corsets & More

The British have a number of sayings that strike listeners of other English-speaking nationalities as odd. “Safe as houses” has always had a curious ring to my American ear, but it turns out to be quite ironic as well: the expression grew popular in the Victorian era, a time when Londoners were as likely to be killed by their own houses as anything else. That, at least, is the impression given by “The Bizarre Ways Victorians Sabotaged Their Own Health & Lives,” the documentary investigation starring historian Suzannah Lipscomb above.

Throughout the second half of the 19th century, many an Englishman would have regarded himself as living at the apex of civilization. He wouldn’t have been wrong, exactly, since that place and time witnessed an unprecedented number of large-scale innovations industrial, scientific, and domestic.

But a little knowledge can be a dangerous thing, and the Victorians’ understanding of their favorite new technologies’ benefits ran considerably ahead of their understanding of the attendant threats. The hazards of the dark satanic mills were comparatively obvious, but even the heights of domestic bliss, as that era conceived of it, could turn deadly.

Speaking with a variety of experts, Lipscomb investigates the dark side of a variety of accoutrements of the Victorian high (or at least comfortably middle-class) life. These harmed not just men but women and children as well: take the breeding-ground of disease that was the infant feeding bottle, or the organ-compressing corset — one of which, adhering to the experiential sensibility of British television, Lipscomb tries on and struggles with herself. Members of the eventual anti-corset revolt included Constance Lloyd, wife of Oscar Wilde, and it is Wilde’s apocryphal final words that come to mind when the video gets into the arsenic content of Victorian wallpaper. “Either that wallpaper goes, or I do,” Wilde is imagined to have said — and as modern science now proves, it could have been more than a matter of taste.

Related Content:

A 108-Year-Old Woman Recalls What It Was Like to Be a Woman in Victorian England

The Color That May Have Killed Napoleon: Scheele’s Green

Poignant and Unsettling Post-Mortem Family Portraits from the 19th Century

Behold the Steampunk Home Exercise Machines from the Victorian Age

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

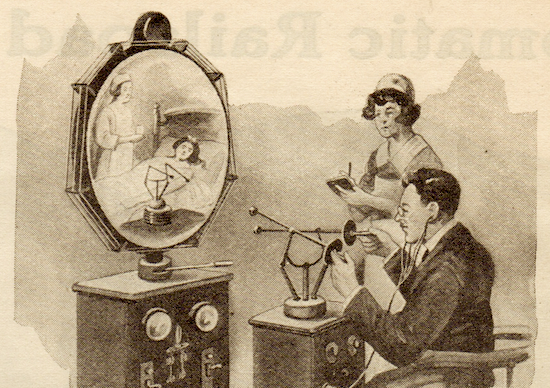

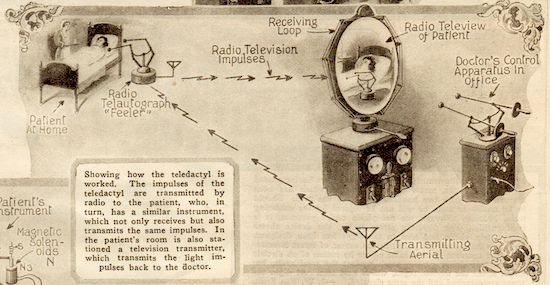

Read More...Sci-Fi Pioneer Hugo Gernsback Predicts Telemedicine in 1925

If you’ve ever wondered why one of science fiction’s greatest honors is called the “Hugo,” meet Hugo Gernsback, one of the genre’s most important figures, a man whose work has been variously described as “dreadful,” “tawdry,” “incompetent,” “graceless,” and “a sort of animated catalogue of gadgets.” But Gernsback isn’t remembered as a writer, but as an editor, publisher (of Amazing Stories magazine), and pioneer of science fact, for it was Gernsback who first introduced the earth-shaking technology of radio to the masses in the early 20th century.

“In 1905 (just a year after emigrating to the U.S. from Germany at the age of 20),” writes Matt Novak at Smithsonian, “Gernsback designed the first home radio set and the first mail-order radio business in the world.” He would later publish the first radio magazine, then, in 1913, a magazine that came to be called Science and Invention, a place where Gernsback could print catalogues of gadgets without the bother of having to please literary critics. In these pages he shone, predicting futuristic technologies extrapolated from the cutting edge. He was understandably enthusiastic about the future of radio. Like all self-appointed futurists, his predictions were a mix of the ridiculous and the prophetic.

Case in point: Gernsback theorized in a 1925 Science and Invention article that communications technologies like radio would revolutionize medicine, in exactly the ways that they have in the 21st century, though not quite through the device Gernsback invented: the “teledactyl,” which is not a robotic dinosaur but a telemedicine platform that would allow doctors to examine, diagnose, and treat patients from a distance with robotic arms, a haptic feedback system, and “by means of a television screen.” Never mind that television didn’t exist in 1925. Sounding not a little like his contemporary Buckminster Fuller, Gernsback insisted that his device “can be built today with means available right now.”

It would require significant upgrades to radio technology before it could support the wireless internet that lets us meet with doctors on computer screens. Perhaps Gernsback wasn’t entirely wrong — technology may have allowed for some version of this in the early 20th century, if medicine had been inspired to move in a more sci-fi direction. But the focus of the medical community — after the devastation of the 1918 flu epidemic — had understandably turned toward disease cure and prevention, not distance diagnosis.

Gernsback looked fifty years ahead, to a time, he wrote, when “the busy doctor… will not be able to visit his patients as he does now. It takes too much time, and he can only, at best, see a limited number today.” Home visits did not last another fifty years, but remote medicine didn’t take their place until almost 100 years after Gernsback wrote. Indeed, the webcams that now give doctors access to patients in the pandemic only came about in 1991 for the purpose of making sure the break room in the computer science department at Cambridge had coffee.

Gernsback even anticipated advances in space medicine, which has spent the last several years building the technology he predicted in order to perform surgeries on sick and injured astronauts stuck months or years away from Earth. He would have particularly appreciated this usage, though he isn’t given credit for the idea. Gernsback also deserves credit for poking fun at himself, as he seemed to realize how hard it was for most people to take him seriously.

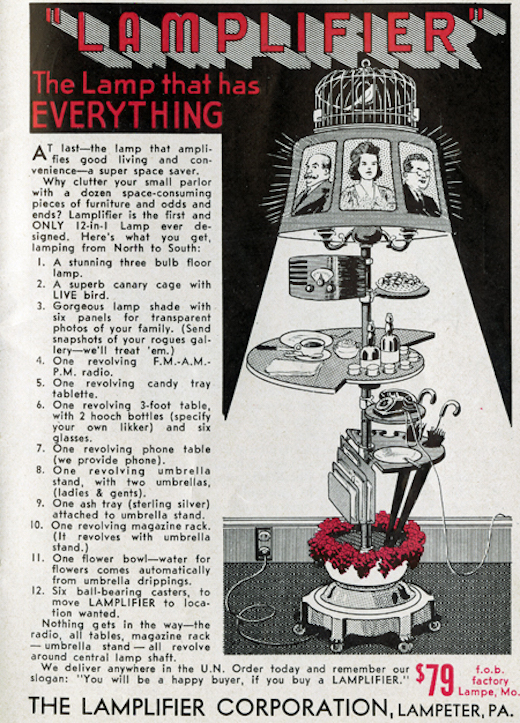

To non-visionaries, the technologies of the future would all seem equally ridiculous today, as in the pages of Gernsback’s satirical 1947 publication, Popular Neckanics Gagazine. Here, we find such objects as the Lamplifier, “the lamp that has EVERYTHING.” Gernsback’s love of gadgets blurred the boundaries between science fiction and fact, always with the strong suggestion that — no matter how useful or how ludicrous — if a machine could be imagined, it could be built and put to work.

Related Content:

A 1947 French Film Accurately Predicted Our 21st-Century Addiction to Smartphones

Sci-Fi Author J.G. Ballard Predicts the Rise of Social Media (1977)

Arthur C. Clarke Predicts in 2001 What the World Will Look By December 31, 2100

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...The Evolutionary History of Fat: Biologists Explain Why It’s Necessary for Our Survival & Why We’re Biased Against It

The Fat Acceptance movement may seem like a 21st century phenomenon, rising to public consciousness with the success of high-profile writers, actors, filmmakers, and activists in recent years. But the movement can date its origins to 1967, when WBAI radio personality Steve Post held a “fat-in” in Central Park, bringing 500 people together to protest, celebrate, and burn diet books and photos of Twiggy. “That same year,” notes the Center for Discovery, “a man named Llewelyn ‘Lew’ Louderback wrote an article for the Saturday Evening Post titled, ‘More People Should be FAT.’” These early sallies led to the founding of the National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance (NAAFA) two years later and more radical groups in the 70s like the Fat Underground.

There would be no need for fat activism, of course, if there were no biases against fat people. This raises the question: where did those biases come from? They are not innate, says Harvard University evolutionary biologist Daniel Lieberman in the Slate video above, but are a product of a history that tracks, coincidentally, with the rise of mass marketing and mass consumerism. We have been sold the idea that thin bodies are better, healthier, more attractive, and more desirable, and that fat is something to be warred against. “However, as an evolutionary biologist, “says Lieberman, I’ve come to appreciate that without fat, we’d be dead. Humans wouldn’t really be the way we are. Fat is really life.”

A quick perusal of art history shows us that larger bodies have been valued around the world in much of human history. We now associate fat with poor health, but it has also signaled the opposite — a storehouse of caloric wealth and healthy fertility. “Our bodies have all sorts of tricks to make sure we never run out of energy,” says Lieberman, “and the main way that we store energy is fat.” Leiberman and other biologists in the video survey the role of fat in human survival and thriving. “Fat is an organ,” and scientists are learning how it communicates with other systems in the body to regulate energy consumption and feed our comparatively enormous brains.

Among animals, “humans are especially adapted to be fat.” Even the thinnest among us are corpulent compared to most primates. Still, the average human did not have any opportunity to become obese until relatively recent historical developments — in the grand evolutionary scheme of things — like agriculture, heavy industry, and the science to preserve and store food. When Europeans discovered sugar, then mass produced it on plantations and exported it around the world, sugar consumption magnified exponentially. The average American now eats 100 pounds of sugar per year. The average hunter-gatherer might have struggled the eat “a pound or two a year” from natural sources.

The over-abundance of calories has led to a type-II diabetes epidemic worldwide that is closely related to sugar consumption. It isn’t necessarily related to having a larger body, although fat deposits in the heart and elsewhere can worsen insulin resistance (and heart disease); the problem is almost certainly linked to excess sugar, the constant availability of high-calorie foods, and low incentives to exercise. Our hunger for sweets and love of comfort are not character flaws, however. They are evolutionary drives that allow us to acquire and conserve energy, operating in a food economy that often punishes us for those very drives. Dieting not only doesn’t work, as neuroscientist Sandra Aamodt explains in her TED Talk above, but it often backfires, making us even hungrier because our brains perceive us as deprived.

As scientists like Lieberman gain a better understanding of the role of fat in human biology, those in the medical community are realizing that doctors and nurses are hardly free from the societal biases against fat. Studies show those biases can translate to poorer medical care and bad advice about dieting, a vicious cycle in which health conditions unrelated to weight go untreated, and are then blamed on weight. Evolutionary biology explains the role of fat in human development, and human history explains its increase, but the question of where the hatred of fat comes from is a trickier one for these scientists to answer. They barely mention the role of advertising and entertainment.

In 1979, activists in the “Fat Liberation Manifesto” identified the problem as fat people’s “mistreatment by commercial and sexist interests” that have “exploited our bodies as objects of ridicule, thereby creating an immensely profitable market selling the false promise of avoidance of, or relief from, that ridicule.” Despite decades of resistance, the diet industry thrives. A Google search of the phrase “body fat” yields page upon page of unscientific advice about ideal body fat percentages, as though reminding the majority of Americans (7 in 10 are classified as overweight or obese) that they should feel there’s something wrong with them.

Blame, shame, and ridicule won’t solve medical problems, say the biologists in the video above, and it certainly doesn’t help people lose weight, if that’s what they need to do. If we better understood the role of fat in keeping us healthy, happy, and alive, maybe we could overcome our hatred of it and accept others, and ourselves, in whatever bodies we’re in.

Related Content:

How the Food We Eat Affects Our Brain: Learn About the “MIND Diet”

Exercise May Prove an Effective Natural Treatment for Depression & Anxiety, New Study Shows

Why Sitting Is The New Smoking: An Animated Explanation

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...17th Century Scientist Gives First Description of Alien Life: Hear Passages from Christiaan Huygens’ Cosmotheoros (1698)

Astrobiologists can now extrapolate the evolutionary characteristics of possible alien life, should it exist, given the wealth of data available on interplanetary conditions. But our ideas about aliens have drawn not from science but from what Adrian Horton at The Guardian calls “an engrossing feedback loop” of Hollywood films, comics books, and sci-fi novels. A little over three-hundred years ago — having never heard of H.G. Wells or the X‑Files — Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens answered the question of what alien life might look like in his work Cosmotheoros, published after his death in 1698.

Everyone knows the names Galileo and Isaac Newton, and nearly everyone knows their major accomplishments, but we find much less familiarity with Huygens, even though his achievements “make him the greatest scientist in the period between Galileo and Newton,” notes the Public Domain Review.

Those achievements include the discovery of Saturn’s rings and its moon, Titan, the invention of the first refracting telescope, a detailed mapping of the Orion Nebula, and some highly notable advancements in mathematics. (Maybe we — English speakers, that is — find his last name hard to pronounce?)

Huygens was a revolutionary thinker. After Copernicus, it became clear to him that “our planet is just one of many,” as scholar Hugo A. van den Berg writes, “and not set apart by any special consideration other than the accidental fact that we happen to be its inhabitants.” Using the powers of observation available to him, he theorized that the inhabitants of Jupiter and Saturn (he used the term “Planetarians”) must possess “the Art of Navigation,” especially “in having so many Moons to direct their Course…. And what a troop of other things follow from this allowance? If they have Ships, they must have Sails and Anchors, Ropes, Pillies, and Rudders…”

“We may well laugh at Huygens,” van den Berg writes, “But surely in our own century, we are equally parochial in our own way. We invariably fail to imagine what we fail to imagine.” Our ideas of aliens flying spacecraft already seem quaint given multiversal and interdimensional modes of travel in science fiction. Huygens had no cultural “feedback loop.” He was making it up as he went. “In contrast to Huygens’ astronomical works, Cosmotheoros is almost entirely speculative,” notes van den Berg — though his speculations are throughout informed and guided by scientific reasoning.

To undermine the idea of Earth as special, central, and unique, “a thing that no Reason will permit,” Huygens wrote — meant posing a potential threat to “those whose Ignorance or Zeal is too great.” Therefore, he willed his brother to publish Cosmotheoros after his death so that he might avoid the fate of Galileo. Already out of favor with Louis XIV, whom Huygens had served as a government scientist, he wrote the book while back at home in The Hague, “frequently ill with depressions and fevers,” writes the Public Domain Review. What did Huygens see in his cosmic imagination of the sailing inhabitants of Jupiter and Saturn? Hear for yourself above in a reading of Huygens’ Cosmotheoros from Voices of the Past.

Huygens’ descriptions of intelligent alien life derive from his limited observations about human and animal life, and so he proposes the necessity of human-like hands and other appendages, and rules out such things as an “elephant’s proboscis.” (He is particularly fixated on hands, though some alien humanoids might also develop wings, he theorizes.) Like all alien stories to come, Huygens’ speculations, however logically he presents them, say “more about ourselves,” as Horton writes, “our fears, our anxieties, our hope, our adaptability — than any potential outside visitor.” His descriptions show that while he did not need to place Earth at the center of the cosmos, he measured the cosmos according to a very human scale.

Related Content:

Richard Feynman: The Likelihood of Flying Saucers

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Brian Eno Day: Hear 10 Hours of Radio Programming Featuring Brian Eno Talking About His Life & Career (1988)

Image via Wikimedia Commons

Brian Eno kept busy during last year’s pandemic, telling the L.A. Times this past January about one of his latest ideas, an open source Zoom alternative, just one of any number of projects he’s kicking around at any given time. One of the most prolific and influential artists, musicians, producers, and thinkers of the past several decades, Eno is such a cultural institution, he warrants his own appreciation day. That’s just what he got on February 12, 1988 when KPFA (a radio station in Berkeley, CA) turned over an entire day to hosting Eno for wide-ranging interviews, stories about his collaborations, and conversations about the musical genres he invented. He even takes questions, and his replies are illuminating and urbane.

Eno’s always been a generous and witty conversationalist. The Brian Eno Day broadcast hits on nearly all of the major highlights of his career up to that point, with a comprehensive overview of his work, earlier interview recordings, and loads of songs and excerpts from his extensive recorded corpus. Much of this work is obscure and much of it is as well-known as the man himself. One cannot tell the stories of artists like U2, Talking Heads, and David Bowie, for example, without talking about Eno’s guiding hand as a producer. Eno’s renowned for founding glam rock pioneers Roxy Music, inventing ambient music, and for his generative approaches to making art, whether on small paper cards or in software and apps.

Eno once said his first musical instrument was a tape recorder, and he’s been obsessed with recording technology ever since, delivering his influential lecture “The Recording Studio as a Compositional Tool” in 1979 and demonstrating its principles in all of the music he’s made. In these interviews, Eno not only discusses the major plot points, but also “reveals such tasty tidbits as his dislike for computer keyboards; an admission that even he does not know what his lyrics mean; a preference for the music of Stockhausen’s students rather than that of Stockhausen himself; and the differences between New Age, Minimal, and Ambient Music,” notes the description on Internet Archive.

In the 33 years since this broadcast, Eno has produced enough music and visual art to fill another 10-hour day of interviews and overviews. But his methods have not changed: he has pursued his later work with the same openness, curiosity, and collaborative spirit he developed in his first few decades. Hear him in his element, ranging far afield in conversations about architecture, genetic evolution, and his own video installation pieces. Eno rarely gets personal, preferring to talk about his work, but it’s humility, not secrecy, that keeps him off the topic of himself. As he recently told a Guardian interviewer, “I’m not f*cking interested at all in me. I want to talk about ideas.” Hear Eno do exactly that in 10 hours of recordings just above.

Related Content:

Behold the Original Deck of Oblique Strategies Cards, Handwritten by Brian Eno Himself

Brian Eno Explains the Origins of Ambient Music

Hear Brian Eno Reinvent Pachelbel’s Canon (1975)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...The Beatles’ 8 Pioneering Innovations: A Video Essay Exploring How the Fab Four Changed Pop Music

In modern society, some facts are simply accepted: one plus one equals two, the Earth revolves around the Sun, and The Beatles are the greatest band in history. “So obviously dazzling was The Beatles’ achievement that few have questioned it,” writes Ian MacDonald in his study of the band Revolution in the Head. “Agreement on them is all but universal: they were far and away the best-ever pop group and their music enriched the lives of millions.” Today, just as half a century ago, most Beatles fans never rigorously examine the basis of the Fab Four’s stature in not just music but culture more broadly. Suffice it to say that no band has ever been as influential, and — more than likely — no band ever will be again.

To each new generation of Beatles fans, however, this very influence has made the band’s innovations more difficult to sense. For decade after decade, practically every major rock and pop band has performed in sports stadia and on international television, made use in the studio of guitar feedback and automatically double-tracked vocals, and shot music videos.

But the Beatles made all these now-common moves first, and others besides, as recounted in the video essay above, “8 Things The Beatles Pioneered.” Its creator David Bennett explains the musical, technological and cultural importance of all these strategies, which have since become so common that they’re seldom named among The Beatles’ many signature qualities.

Not absolutely everyone loves The Beatles, of course. But even those who don’t particularly enjoy their records must acknowledge their Shakespearean, even Biblical super-canonical status in popular music today. This can actually make it somewhat intimidating to approach the music of The Beatles, despite its very popularity, and especially for those of us who weren’t drawn to it growing up. I myself only recently listened through the Beatles canon, at the age of 35, an experience I’d deferred for so long knowing it would send me down an infinitely deep rabbit hole of associated reading. If you, too, consider yourself a candidate for late-onset Beatlemania, consider starting with the half-hour video just above, which tells the story of the band’s origins — and thus the origin, in a sense, of the pop culture that still surrounds us.

Related Content:

How “Strawberry Fields Forever” Contains “the Craziest Edit” in Beatles History

Hear the Beautiful Isolated Vocal Harmonies from the Beatles’ “Something”

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

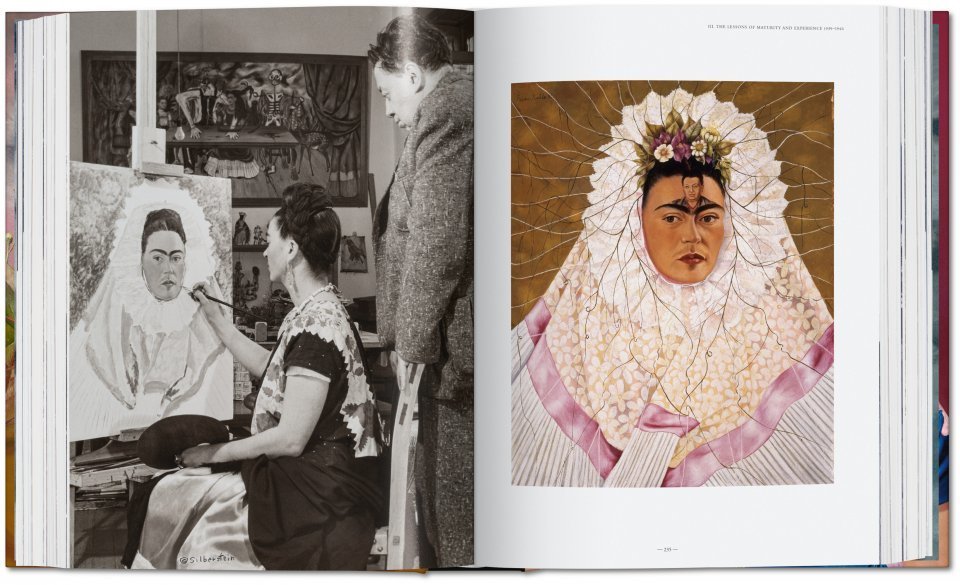

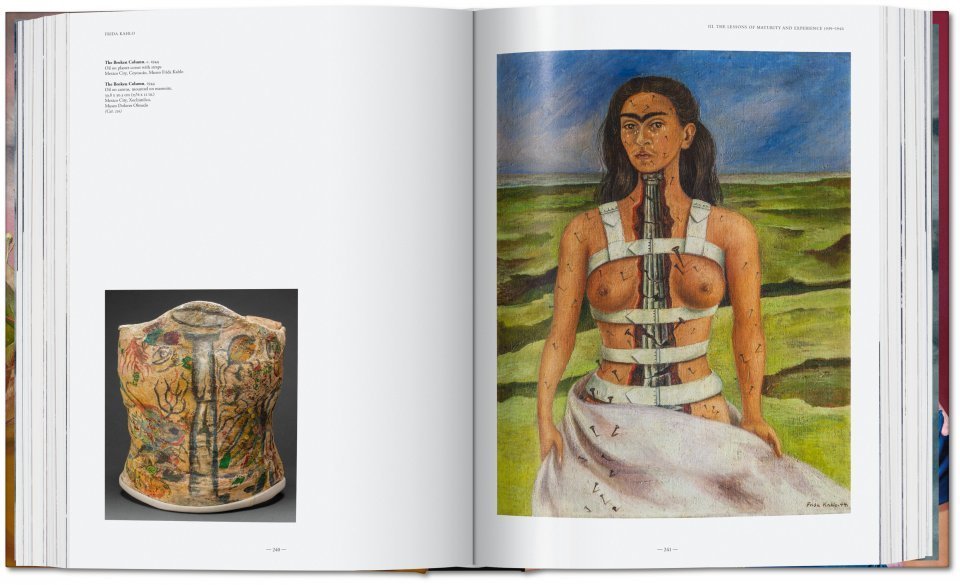

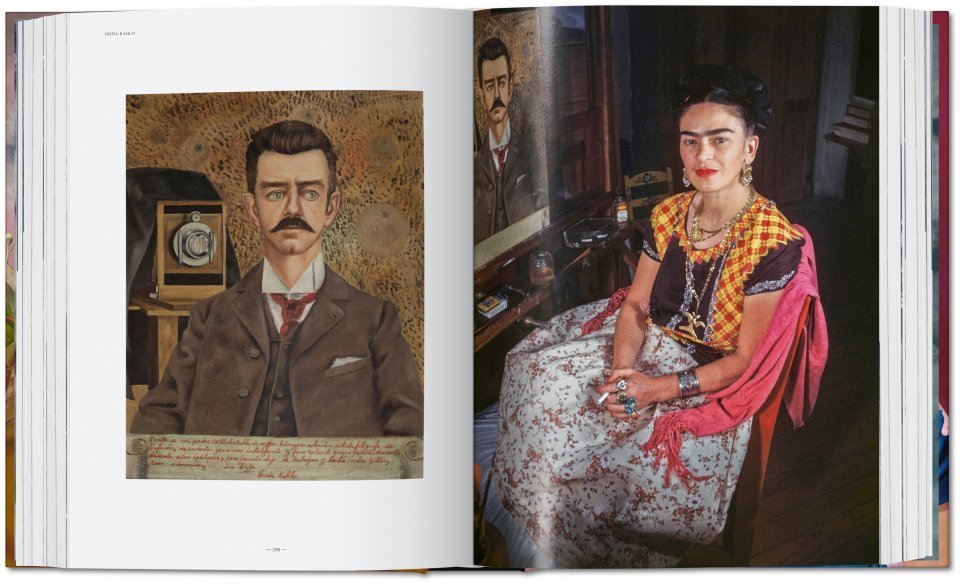

Read More...Frida Kahlo: The Complete Paintings Collects the Painter’s Entire Body of Work in a 600-Page, Large-Format Book

Most of us who know Frida Kahlo’s work know her self-portraits. But, in her brief 47 years, she created a more various body of work: portraits of others, still lifes, and difficult-to-categorize visions that still, 67 years after her death, feel drawn straight from the wild currents of her imagination. (Not to mention her elaborately illustrated diary, previously featured here on Open Culture.) Somehow, Kahlo’s work has never all been gathered in one place. That, along with her enduring appeal as both an artist and a historical figure, surely made her an appealing proposition for art-book publisher Taschen, an operation as invested in visual richness as it is in completeness.

There’s also the matter of size. Though not conceived at the same scale as the murals of Diego Rivera, with whom Kahlo lived in not one but two less-than-conventional marriages, Kahlo’s paintings look best when seen at their biggest. Hence Taschen’s “large-format XXL” production of Frida Kahlo: The Complete Paintings, which “allows readers to admire Frida Kahlo’s paintings like never before, including unprecedented detail shots and famous photographs.” Presented along with a biographical essay, those photos capture, among other subjects, “Frida, Diego, and the Casa Azul, Frida’s home and the center of her universe.”

In creating his volume, editor-author Luis-Martín Lozano and contributors Andrea Kettenmann and Marina Vázquez Ramos focused not on the artist’s life, but her work. “Most people at exhibitions, they’re interested in her personality — who she is, how she dressed, who does she go to bed with, her lovers, her story,” says Lozano in an interview with BBC Culture. Putting together a run-of-the-mill Kahlo book, “you repeat the same things, and it will sell – because everything about Kahlo sells. It’s unfortunate to say, but she’s become a merchandise.” Frida Kahlo: The Complete Paintings is also, of course, a product, and one painstakingly designed to compel the Frida Kahlo enthusiast. Its ideal reader, however, desires to live in not Kahlo’s world, but the world she created.

via Colossal

Related Content:

Frida Kahlo: The Life of an Artist

The Intimacy of Frida Kahlo’s Self-Portraits: A Video Essay

Take a Virtual Tour of Frida Kahlo’s Blue House Free Online

A Brief Animated Introduction to the Life and Work of Frida Kahlo

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...