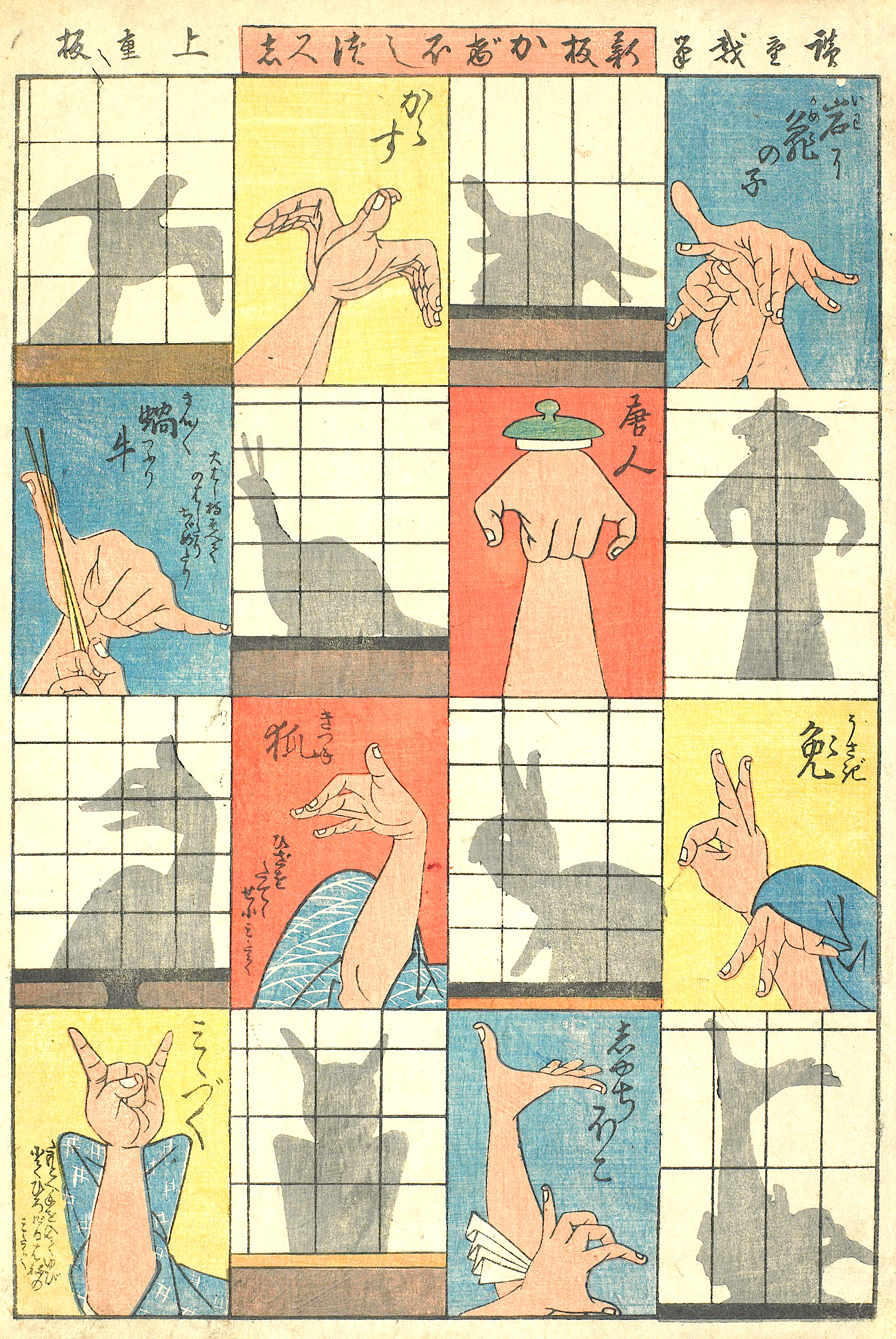

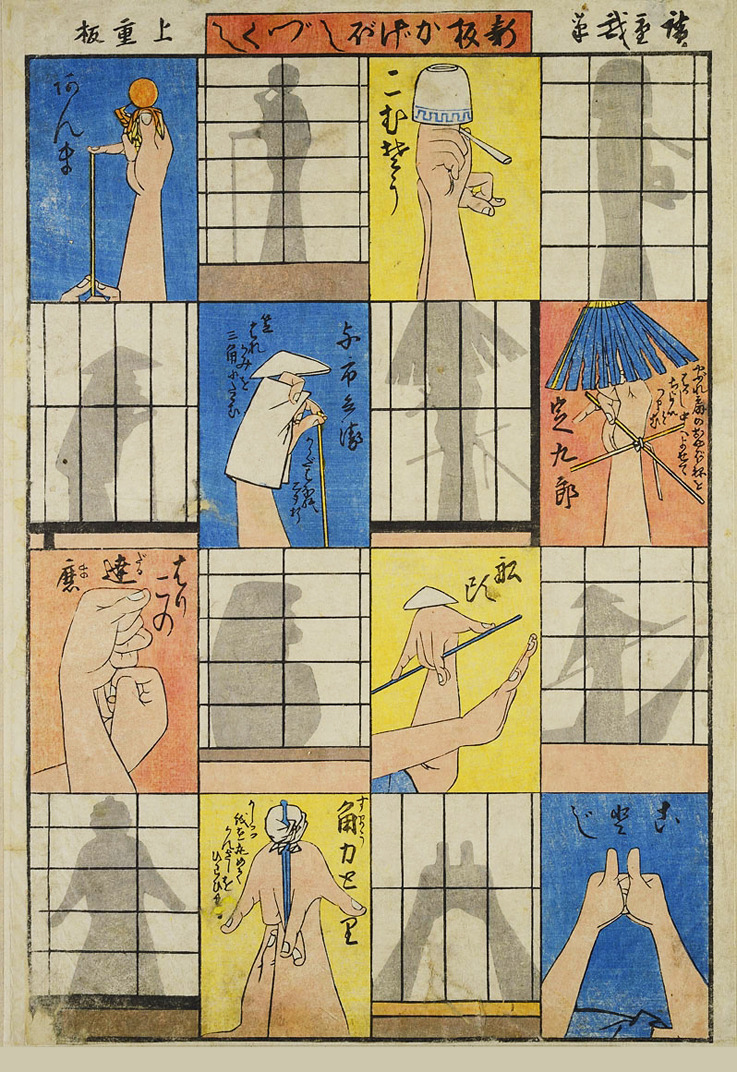

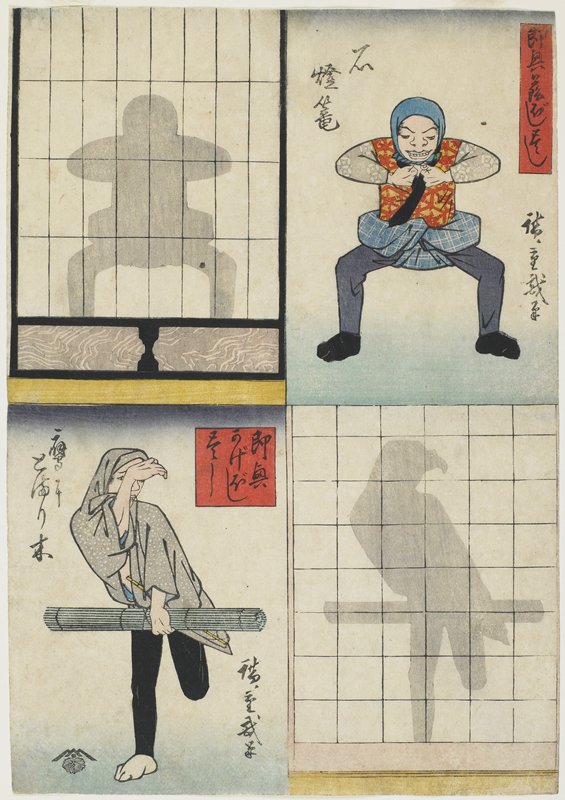

Hiroshige, Master of Japanese Woodblock Prints, Creates a Guide to Making Shadow Puppets for Children (1842)

Even if the name Utagawa Hiroshige doesn’t ring a bell, “Hiroshige” by itself probably does. And on the off chance that you’ve never heard so much as his mononym, you’ve still almost certainly glimpsed one of his portrayals of Tokyo — or rather, one of his portrayals of Edo, as the Japanese capital, his hometown, was known during his lifetime. Hiroshige lived in the 19th century, the end of the classical period of ukiyo‑e, the art of woodblock-printed “pictures of the floating world.” In that time he became one of the form’s last masters, having cultivated not just a high level of artistic skill but a formidable productivity.

In total, Hiroshige produced more than 8,000 works. Some of those are accounted for by his well-known series of prints like The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō, The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kisokaidō, One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. But his mastery encompassed more than the urban and rural landscapes of his homeland, as evidenced by this much humbler project: a set of omocha‑e, or instructional pictures for children, explaining how to make shadow puppets.

Hiroshige explains in clear and vivid images “how to twist your hands into a snail or rabbit or grasp a mat to mimic a bird perched on a branch,” writes Colossal’s Grace Ebert. “Appearing behind a translucent shoji screen, the clever figures range in difficulty from simple animals to sparring warriors and are complete with prop suggestions, written instructions for making the creatures move — ‘open your fingers within your sleeve to move the owl’s wings’ or ‘draw up your knee for the fox’s back’ — and guides for full-body contortions.” The difficulty curve does seem to rise rather sharply, beginning with puppets requiring little more than one’s hands and ending with full-body performances surely intended more for amusement than imitation.

But then, kids take their fun wherever they find it, whether in 2021 or in 1842, when these images were originally published. Though it was a fairly late date in the life of Hiroshige, at that time modern Japan hadn’t even begun to emerge. The children who entertained themselves with his shadow puppets against the shoji screens of their homes would have come of age with the arrival of United States Commodore Matthew C. Perry’s “black ships,” which began the long-closed Japan’s process of re-opening itself to world trade — and set off a whirlwind of civilizational transformation that, well over a century and a half later, has yet to settle down.

Related Content:

Wagashi: Peruse a Digitized, Centuries-Old Catalogue of Traditional Japanese Candies

Jim Henson Teaches You How to Make Puppets in Vintage Primer From 1969

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...The Making of a Marble Sculpture: See Every Stage of the Process, from the Quarry to the Studio

Some marble statues, even when stripped of their color by the sands of time since the heyday of Greece and Rome, look practically alive. But they began their “lives,” their appearance often makes us forget, as rough-hewn blocks of stone. Not that just any marble will do: following the example of Michelangelo, the discerning sculptor must make the journey to the Tuscan town of Carrara, “home of the world’s finest marble.” So claims the video above, a brief look at the process of Hungarian sculptor Márton Váró. That entire process, it appears, takes place in the open air: mostly in his outdoor studio space, but first at the Carrara quarry (see bottom video) where he picks just the right block from which to make his vision emerge.

Like Michelangelo, Váró has a manifestly high level of skill at his disposal — and unlike Michelangelo, a full set of modern power tools as well. But even today, some sculptors work without the aid of angle cutters and diamond-edged blades, as you can see in the video from the Getty above.

In it a modern-day sculptor introduces traditional tools like the point chisel, the tooth chisels, and the rasp, describing the different effects achievable with them by using different techniques. If you “lose your ego and just flow into the stone through your tools,” he says, “there’s no end of possibilities of what you can do inside that space” — the space of limitless possibilities, that is, afforded by a simple block of marble.

In the video above, sculptor Stijepo Gavrić further demonstrates the proper use of such hand tools, painstakingly refining a roughly human form into a lifelike version of an already realistic clay model — and one that holds up quite well alongside the original model, when she shows up for a comparison. The Great Big Story documentary short below takes us back to Tuscany, and specifically to the town of Pietrasanta, where marble has been quarried for five centuries from a mountain first discovered by Michelangelo.

It’s also home to hardworking sculptors well known for their ability to replicate classic and sacred works of art. “Marble is my life, because in this area you feed off marble,” says one who’s been at such work for about 60 years. If stone gives the artist life, it does so only to the extent that he breathes life into it.

Related Content:

Watch a Masterpiece Emerge from a Solid Block of Stone

Michelangelo’s David: The Fascinating Story Behind the Renaissance Marble Creation

How Ancient Greek Statues Really Looked: Research Reveals Their Bold, Bright Colors and Patterns

Roman Statues Weren’t White; They Were Once Painted in Vivid, Bright Colors

Rare Film of Sculptor Auguste Rodin Working at His Studio in Paris (1915)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Brian Eno Launches His Own Radio Station with Hundreds of Unreleased Tracks: Hear Two Programs

Creative Commons image via Wikimedia Commons

Back in 2013, Brian Eno gave a talk at the Red Bull Academy, the lecture series that has hosted fellow musicians like Tony Visconti, Debbie Harry, and Nile Rogers. Asked when he knew a piece of music was finished, Eno let drop that he currently had 200,809 works of unreleased music. (The actual answer though? “When there’s a deadline”).

Usually we have to wait for posthumous releases to hear such music, like what is currently happening now to Prince’s “vault” of music. Eno is not waiting. He got the deadline.

Sonos Radio HD, the music division of the speaker and audio system company, announced last week that Eno has curated a radio station that will play nothing but unreleased cuts from his five decades of making music. There’s so much material, the chance of a listener hearing a repeat is slim. (Still, the station promises hundreds of tracks, not hundreds of thousands.)

Now, this is not an advertisement for Sonos, but a heads up that in order to promote “The Lighthouse,” as Eno has called the radio station, Sonos has dropped two Eno-led radio shows where he shares just a fraction of the unreleased material, with a promise of two more episodes to come. One features an interviewer, and the other is just Eno talking about the tracks. (And you *can* get one month free at Sonos if you sign up.)

“(A radio station) is something I’ve been thinking about for years and years and years,” says Eno. “And it’s partly because I have far too much music in my life. I have so much stuff.”

The tracks have been purged of titles and have been instead given the utilitarian monikers of “Lighthouse Number (X)”. Anyway, titles suggest too much thought. “Some are pretty crap titles,” he says. “The problem with working on computers is that you have to give things titles before you’ve actually made them…Sometimes the pieces often quickly outgrow the titles.”

If you’re expecting nothing but ambient washes and generative music, you might be surprised at the variety. In the first Eno-hosted show, he plays a funky jam (“Lighthouse Number 002”) co-composed by Peter Chilvers and stuffed with r’n’b samples; and an almost-completed song featuring the Eurythmics’ Dave Stewart on guitar, called “All the Bloody Fighters,” aka “Lighthouse Number 106”.

Why call it “The Lighthouse”? “I like the idea of a sort of beacon calling you, telling you something, warning you perhaps, announcing something.” He also credits a friend who told him his unreleased music is like ships lost at sea. The lighthouse “is calling in some of those lost ships.”

As a bonus, listen below to Eno’s recent interview with Rick Rubin, where they talk about the Sonos project and much more.

Related Content:

Hear Brian Eno’s Rarely-Heard Cover of the Johnny Cash Classic, “Ring of Fire”

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his films here.

Read More...Hear The Velvet Underground’s “Legendary Guitar Amp Tapes,” Which Showcases the Brilliance & Innovation of Lou Reed’s Guitar Playing (1969)

What was the Velvet Underground? A Kim Fowly-like art project that outlived its impresario’s interest? A main vehicle for Lou Reed, rock’s egomaniac underdog (who was no one’s ingénue)? Was it three bands? 1. The Velvet Underground and Nico; 2. The Velvet Underground with John Cale; and 3. The Velvet Underground with Doug Yule after Cale’s departure. (Let’s pass by, for the moment, whether VU without Reed warrants a mention…)

Each iteration pioneered essential underground sounds — dirgy Euro-folk rock, strung-out New York garage rock, junkie ballads, psychedelic drone, experimental noise — nearly all of them channeled through Reed’s underrated guitar playing, which was, perhaps the most important member of the band all along. Whoever taped the Velvets (in their second incarnation) on March 15, 1969, on the last night of a three-show engagement at The Boston Tea Party in Boston, MA, seemed to think so. “The entire set was recorded by a fan directly from Lou Reed’s guitar amplifier,” MetaFilter points out.

The mic jammed in the back of Reed’s amp, a Head Heritage reviewer writes, produced “a mighty electronic roar that reveals the depth and layers of Reed’s playing. Over and undertones, feedback, string buzz, the scratch of fingers on frets and the crackle and hum of tube amps combine to create a monolithic blast of metal machine music.” Known as the “legendary guitar amp tape” and long sought by collectors and fans, the bootleg, which you can hear above, “serves as a testament to the brilliance and innovation of Reed’s guitar-playing — both qualities that are often underrated, if not overlooked entirely, by critics of his work,” as Richie Unterberger writes.

It should be evident thus far that these recordings are hardly a comprehensive document of the Velvet Underground in early 1969. Except for Mo Tucker’s glorious, but muffled thumping and some of Sterling Morrison’s excellent guitar interplay, the rest of the band is hardly audible. Songs like “Candy Says” and “Jesus” — on which Reed does not create sublime swirls of noise and feedback — chug along monotonously without their melodies. “It is frustrating,” Unterberger admits, “to hear such a one-dimensional audio-snapshot of what is clearly a good — if not great — night for the band” (who were far more than one of their parts). On the other hand, nowhere else can we hear the nuance, ferocity, and outright insanity of Reed’s playing so amply demonstrated on the majority of this document.

The tape circulated for years as a Japanese bootleg, an interesting fact, notes a Rate Your Music commenter, “considering this bears more similarity to recordings from the likes of [legendary Japanese psych rock band] Les Rallizes Dénudés than most of the Velvet Underground’s other material.” The recordings may have well paved the way for the explosion of Japanese psychedelic rock to come. They also demonstrate the influence of Ornette Coleman in Reed’s playing, and the liberating philosophy Coleman would come to call Harmolodics.

“Alla that boo-ha about whether Reed really was influenced by free jazz,” writes one reviewer quoted on MetaFilter, “can be put to rest here as he pulls the kind of wailing hallucinatory shapes from the guitar that it would take the goddam Blue Humans to decode a couple of decades later.” It may well overstate the case to claim that “Lou Reed single-handedly invented underground music,” but we can hear in these recordings the seeds of everything from Television to Sonic Youth to Pavement to Royal Trux and so much more. See the full tracklist below, a “classic setlist,” notes MetaFilter, “from around the time of their 3rd LP.”

I Can’t Stand It

Candy Says

I’m Waiting For The Man

Ferryboat Bill

I’m Set Free

What Goes On

White Light White Heat

Beginning To See The Light

Jesus

Heroin / Sister Ray

Move Right In

Run Run Run

Foggy Notion

Related Content:

Hear Ornette Coleman Collaborate with Lou Reed, Which Lou Called “One of My Greatest Moments”

The Velvet Underground Captured in Color Concert Footage by Andy Warhol (1967)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Sci-Fi “Portal” Connects Citizens of Lublin & Vilnius, Allowing Passersby Separated by 376 Miles to Interact in Real Time

Can we ever transcend our tendency to divide up the world into us and them? The history of Europe, which political theorist Kenneth Minogue once called “plausibly summed up as preparing for war, waging war, or recovering from war,” offers few consoling answers. But perhaps it isn’t for history, much less for theory or politics, to dictate the future prospects for the unity of mankind. Art and technology offer another set of views on the matter, and it’s art and technology that come together in Portal, a recently launched project that has connected Vilnius, Lithuania and Lublin, Poland with twin installations. More than just a sculptural statement, each city’s portal offers a real-time, round-the-clock view of the other.

“In both Vilnius and Lublin,” writes My Modern Met’s Sara Barnes, “the portals are within the urban landscape; they are next to a train station and in the city central square, respectively. This allows for plenty of engagement, on either end, with the people of a city 376 miles apart. And, in a larger sense, the portals help to humanize citizens from another place.”

Images released of the interaction between passerby and their local portal show, among other actions, waving, camera phone-shooting, synchronized jumping, and just plain staring. Though more than one comparison has been made to the Stargate, the image also comes to mind of the apes around the monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey, reacting as best they can to a previously unimagined presence in their everyday environment.

Ironically, the basic technology employed by the Portal project is nothing new. At this point we’ve all looked into our phone and computer screens and seen a view from perhaps much farther than 376 miles away, and been seen from that distance as well. But the coronavirus-induced worldwide expansion of teleconferencing has, for many, made the underlying mechanics seem somewhat less than miraculous. Conceived years before travel restrictions rendered next to impossible the actual visiting of human beings elsewhere on the continent, let alone on the other side of the world, Portal has set up its first installations at a time when they’ve come to feel like something the world needs. “Residents in Reykjavik, Iceland, and London, England can expect a portal in their city in the future,” notes Barnes — and if those two can feel truly connected with Europe, there may be hope for the oneness of the human race yet.

Related Content:

This Huge Crashing Wave in a Seoul Aquarium Is Actually a Gigantic Optical Illusion

See Web Cams of Surreally Empty City Streets in Venice, New York, London & Beyond

The History of Europe from 400 BC to the Present, Animated in 12 Minutes

Haruki Murakami Novels Sold in Polish Vending Machines

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...The Psychology of Video Game Engagement — Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #94 with Jamie Madigan

Why do people play video games, and what keeps them playing? Do we want to have to think through innovative puzzles or just lose ourselves in mindless reactivity? Your hosts Mark Linsenmayer, Erica Spyres, and Brian Hirt are joined by Dr. Jamie Madigan, an organizational psychologist who runs the Psychology of Video Games podcast, to discuss what sort of a thing this is to research, the evolution of games, player types, motivation vs. engagement, incentives and feedback, as well as the gamification of work or school environments. Some games we touch on include Donkey Kong, Dark Souls, It Takes Two, Returnal, Hades, Subnautica, Fortnite, and Age of Z.

Some of the episodes of Jamie’s podcast relevant for our discussion are:

- Ep. 3 on psychological flow in games

- Ep. 6 on using psychology to craft user experiences

- Ep. 9 on how games differ from other media

Check out his books and articles too. Here are a couple of additional sources about engagement:

- “The Player Engagement Process– An Exploration of Continuation Desire in Digital Games” by Henrik Schoenau-Fog

- “Understanding Video Gaming’s Engagement” by Eric Gregory

The site Erica mentions about disabled modes in gaming is caniplaythat.com.

Hear more of this podcast at prettymuchpop.com. This episode includes bonus discussion that you can access by supporting the podcast at patreon.com/prettymuchpop. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network.

Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts.

Read More...Download 1,000+ Beautiful Woodblock Prints by Hiroshige, the Last Great Master of the Japanese Woodblock Print Tradition

For 200 years, beginning in the 1630s, Japan closed itself off from the world. In its capital of Edo the country boasted the largest city in existence, and among its population of more than a million not a single one was foreign-born. “Practically the only Europeans to have visited it were a handful of Dutchmen,” writes professor of Japanese history Jordan Sand in a new London Review of Books piece, “and so it would remain until the mid-19th century. No foreigners were permitted to live or trade on Japanese soil except the Dutch and Chinese, who were confined to enclaves in the port of Nagasaki, 750 miles from Edo. No Japanese were permitted to leave: those who disobeyed did so on pain of death.”

These centuries of isolation in the Japanese capital — known today as Tokyo — thus produced next to nothing in the way of Westerner-composed accounts. But “the people of Edo themselves left a rich archive,” Sand notes, given the presence among them of no few individuals highly skilled in the literary and visual arts.

Such notable Edo chroniclers include Andō Hiroshige, the samurai-descended son of a fireman who grew up to become Utagawa Hiroshige, or simply Hiroshige, one of the last masters of the ukiyo‑e woodblock-printing tradition.

Hiroshige’s late “pictures of the floating world” are among the most vivid images of life in Japan just before it reopened, works that Sand quotes art historian Timon Screech as claiming “attest to a new sense of Edo’s place in the world.” For the historiographical view of the sakoku (or “closed country”) policy has long since come in for revision. The Japan of the mid-17th to late 19th century may not actually have been as closed as all that, or at least not as free of foreign influence as previously assumed. The evidence for this proposition includes Hiroshige’s ukiyo‑e prints, especially his late series of masterworks One Hundred Famous Views of Edo.

Now, thanks to the Minneapolis Institute of Art’s digital collection, you can take as long and as close a look as you’d like at — and even download — more than 1,000 of his works. That’s an impressive number for a single institution, but bear in mind that Hiroshige produced about 8,000 pieces in his lifetime, capturing not just the attractions of Edo but views from all over his homeland as he knew it, which had already begun to vanish in the last years of his life. More than a century and a half on, the coronavirus pandemic has prompted Japan to put in place entry restrictions that, for many if not most foreigners around the world, have effectively re-closed the country. Japan itself has changed a great deal since the mid-19th century, but to much of the world it has once again become a land of wonders accessible only through its art. Explore 1,000+ woodblock prints by Hiroshige here.

Related Content:

Download Hundreds of 19th-Century Japanese Woodblock Prints by Masters of the Tradition

Download 2,500 Beautiful Woodblock Prints and Drawings by Japanese Masters (1600–1915)

Enter a Digital Archive of 213,000+ Beautiful Japanese Woodblock Prints

The Real Locations of Ukiyo‑e, Historic Japanese Woodblock Prints, Plotted on a Google Map

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Sonic Explorations of Japanese Jazz: Stream 8 Mixes of Japan’s Jazz Tradition Free Online

“Man,” a fellow working the checkout counter at Los Angeles’ Amoeba Music once said to me, “you sure do like Japanese jazz.” His tone was one of faint disbelief, but then, this particular record-shopping trip happened well over a decade ago. Since then the global listenership of Japanese jazz has increased enormously, thanks to the expansion of audiovisual streaming platforms and the enterprising collectors and curators who’ve used them to share the glory of the most American of all art forms as mastered and re-interpreted by dedicated musicians in the Land of the Rising Sun.

High-profile Japanese-jazz enthusiasts of the 2020s include the Turkish DJ Zag Erlat, creator of the Youtube channel My Analog Journal, whose short 70s mix of the stuff we featured last year here on Open Culture. But it was only a matter of time before the musical minds at London-based online radio station NTS broadcast the definitive Japanese Jazz session to the world.

Previously, NTS have dedicated large blocks of airtime to projects like the history of spiritual jazz and a tribute to the favorite music of novelist Haruki Murakami — a Japanese man and a jazz-lover, but one whose America-inspired cultural energy hasn’t been particularly directed toward jazz of the Japanese variety.

“Japanese jazz” refers not to a single genre, but to a variety of different kinds of jazz given Japanese expression. Hence NTS’ Japanese Jazz Week, each of whose bilingually announced broadcasts specializes in a different facet of the music. The first mix is dedicated to the late guitarist Ryo Kawasaki; the second, to traditional Japanese instruments like the shakuhachi, and the koto; the third, to Three Blind Mice, often described as “the Japanese Blue Note”; the fourth, to jazz fusion, one of the musical currents in Japan that gave rise to city pop in the 1980s; the fifth, to pianist Masabumi Kikuchi, who played with the likes of Sonny Rollins and Miles Davis; the sixth, to modal jazz and bop from the 1960s to the 1980s; and the seventh, to free-improvising saxophonist Kaoru Abe, “a true maverick of late 70’s Japanese jazz.”

Japanese Jazz Week also includes a special on spiritual and free jazz as played in Japan “from its earliest stirrings in the 1960s until it reached international recognition in the 1970s.” The 70s, as the international fan consensus appears to reflect, was the golden age of Japanese jazz; as I recall, the heap of LPs I set down before that Amoeba clerk came mostly from that decade. The decade’s players, producers, labels, and concert venues continue their work today, the current pandemic-related difficulties of live performance aside. When the shows start and travel resumes again in earnest, no small number of Japanese-jazz fans will be booking their tickets to Tokyo at once, all in search of an offline Japanese Jazz Week — or two or three — of their own.

Related Content:

Hear Enchanting Mixes of Japanese Pop, Jazz, Funk, Disco, Soul, and R&B from the 70s and 80s

Hear a 9‑Hour Tribute to John Peel: A Collection of His Best “Peel Sessions”

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Watch a New Director’s Cut of Prince’s Blistering “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” Guitar Solo (2004)

Recently, I was walking with a young relative who, upon passing a mural of the late Prince Rogers Nelson, looked up at me and asked, “who is that?,” whereupon my eyes grew wide as saucers and I began the tale of a musical hero who conquered every instrument, every musical style, every chord and scale, etc. It was a story fit for young ears, mind you, but mythic enough, I guess, that it inspired my relative to stop me mid-sentence and ask in awe, “was he a god?” To which I stammered, caught off guard, “well, kind of…..”

Humanly flawed though he was, Prince comes as close as any recent figure to musical divinity in the flesh. He seemed to conjure and create effortlessly, ex nihilo, never seeming to tire and always looking as though he just stepped off of a cloud. Now we know a little more about the source of some of that serenity, but it diminishes his legend not one bit. If not a god, he was at least some sort of wizard.

Prince’s famously epic live solo at the 2004 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony in the star-packed jamboree cover of George Harrison’s “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” holds up as a wondrously succinct case in point to show the children. Now, the performance has been re-edited in a “director’s cut” by the broadcast’s original director Joel Gallen. Thom Dunn at Boing Boing quotes his explanation: “there were several shots that were bothering me. I got rid of the dissolves and made them all cuts, and added lots more close ups of Prince during his solo.” (See the original below.)

“Fortunately,” notes Dunn, “Gallen preserved the disappearing guitar at the end.” No one knows to this day where the guitar went, not even Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers drummer Steve Ferrone, who was on stage behind Prince at the time. The stunt was unrehearsed, and so was everything about the solo — no one had any idea what was going to happen, a frightening prospect on live television but a risk one must take, I suppose, when working with the Purple One.

In 2016, Gallen told The New York Times the story, worth quoting in full, of the performance’s rehearsal, a moment of private humility from Prince behind his live bravura show onstage.

The Petty rehearsal was later that night. And at the time I’d asked him to come back, there was Prince; he’d shown up on the side of the stage with his guitar. He says hello to Tom and Jeff and the band. When we get to the middle solo, where Prince is supposed to do it, Jeff Lynne’s guitar player just starts playing the solo. Note for note, like Clapton. And Prince just stops and lets him do it and plays the rhythm, strums along. And we get to the big end solo, and Prince again steps forward to go into the solo, and this guy starts playing that solo too! Prince doesn’t say anything, just starts strumming, plays a few leads here and there, but for the most part, nothing memorable.

They finish, and I go up to Jeff and Tom, and I sort of huddle up with these guys, and I’m like: “This cannot be happening. I don’t even know if we’re going to get another rehearsal with him. [Prince]. But this guy cannot be playing the solos throughout the song.” So I talk to Prince about it, I sort of pull him aside and had a private conversation with him, and he was like: “Look, let this guy do what he does, and I’ll just step in at the end. For the end solo, forget the middle solo.” And he goes, “Don’t worry about it.” And then he leaves. They never rehearsed it, really. Never really showed us what he was going to do, and he left, basically telling me, the producer of the show, not to worry. And the rest is history. It became one of the most satisfying musical moments in my history of watching and producing live music.

No, kid, he wasn’t a god, just a guy who could do things no one else could. He was a genius.

via Boing Boing / Laughing Squid

Related Content:

Prince Plays a Mind-Blowing Guitar Solo On “While My Guitar Gently Weeps”

Prince’s First Television Interview (1985)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Kermit the Frog Gives a TED Talk About Creativity & the Power of “Ridiculous Optimism”

In 2015, 3.8 billion years after “creativity emerged” out of “sheerest emptiness,” Kermit the Frog was tapped to give a talk on creativity at TEDxJackson.

How did a local, one-day event manage to snag such a global icon?

Roots.

The famed frog’s creator, Jim Henson, spent his first decade in Mississippi (though Kermit was born of a ping pong ball and Henson’s mother’s old coat after the family relocated to Maryland.)

The conference took place 15 years after Henson’s untimely death, leaving Kermit to be animated by Steven Whitmire, the first of two puppeteers to tackle a role widely understood to be Henson’s alter ego.

The voice isn’t quite the same, but the mannerisms are, including the throat clearing and crumpled facial expressions.

Also present are a number of TED Talk tropes, the smart phone prompts, the dark stage, projections designed to emphasize profound points.

A number of jokes fail to elicit the expected laughs … we’ll leave it up to you to determine whether the fault lays with the live audience or the material. (It’s not easy being green and working blue comes with challenges, too.)

Were he to give his TED Talk now, in 2021, Kermit probably wouldn’t describe the audience’s collective decision to “accept a premise, suspend our disbelief and just enjoy the ride” as a “conspiracy of craziness.”

He might bypass a binary quote like “If necessity is the mother of invention, then creativity is the father.”

He’d also be advised to steer clear of a photo of Miss Piggy dressed as a geisha, and secure her consent to share some of the racier anecdotes… even though she is a known attention hog.

He would “transcend and include” in the words of philosopher Ken Wilber, one of many inspirations he cites over the course of his 23-minute consideration of creativity and its origins, attempting to answer the question, “Why are we here?”

Also referenced: Michelangelo, Albert Einstein, Salvador Dali, Charles Baudelaire, Zen master Shunryū Suzuki, mathematician Alfred North Whitehead, author and educator, Sir Ken Robinson (who appears, briefly) and of course, Henson, who applauded the “ridiculous optimism” of flinging oneself into creative explorations, unsure of what one might find.

He can’t wander freely about the stage, but he does share some stirring thoughts on collaboration, mentors, and the importance of maintaining “beginner’s mind,” free of pre-conceptions.

How to cultivate beginner’s mind?

Try fast forwarding to the 11:11 mark. Watch for 20 seconds. It’s the purest invitation to believe since Peter Pan begged us to clap Tinker Bell back to life.

Do you? Because Kermit believes in you.

Related Content:

Witness the Birth of Kermit the Frog in Jim Henson’s Live TV Show, Sam and Friends (1955)

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...