What Makes Ringo Starr a Great Drummer: Demonstrations from a German Teenager & Ringo Himself

The question of whether or not Ringo Starr is a great rock drummer — maybe one of the greatest– seems more or less settled among drummers. “From the simplistic heavy-hitting of Dave Grohl, to the progressive mind bending of Mike Portnoy, and way beyond,” writes Stuart Williams at Music Radar, “all roads lead back to Ringo.” Not only is Ringo “your favorite drummer’s favorite drummer,” but when he took the stage in 1964 on The Ed Sullivan Show, “you’d be hard-pushed to find another moment where one drummer inspired an entire generation of kids and teenagers to pick up a pair of sticks and beg their parents to buy them a kit.”

There was little precedent for what he did in rock drumming even in the band’s earliest years. Ringo helped change “the role of the drums from an orthodox, military and jazz-led discipline into a more democratised art form. If there was a blueprint for what drummers ‘did’ in rock ’n’ roll, Ringo’s approach widened it,” adds Music Radar. Much of his expansive vocabulary was accidental, at least at first, a product of what Beatles biographer Bob Spitz calls a childhood beset by “a Dickensian chronicle of misfortune.”

Like many a groundbreaking musician, Ringo played at what might be considered a physical disadvantage. He learned the drums in “the hospital band,” he once said, while convalescing from tuberculosis. “My grandparents gave me a mandolin and a banjo, but I didn’t want them. My grandfather gave me a harmonica… we had a piano — nothing. Only the drums.” Like Hendrix, he was a lefty forced to adapt to a right-handed version of the instrument, thus enlarging what right- (and left) handed drummers thought could be done with it.

As German drummer Sina demonstrates at the top of the post, Ringo’s unique style involves a great deal of subtlety, “tone, taste, musicality, and that left-handed drummer on a right-handed kit reverse-fell tom-tom work,” writes Boing Boing. We’ve previously featured Sina in a post in which great drummers pay tribute to Ringo. The daughter of a musician in German Beatles tribute band the Silver Beatles, she shows off an unimpeachable grasp of Starr’s signature moves.

In the clip above, Ringo himself demonstrates his technique on “Ticket to Ride,” “Come Together,” and his highest-charting solo single “Back Off Boogaloo.” In explaining how he employed his most highly praised talent — playing exactly what the song needed and no more — he shows how the drum pattern in the Abbey Road opener came directly from John’s vocals and Paul’s bass line. In “Ticket to Ride,” he shows how he works from his shoulder, producing a downbeat that’s slightly ahead.

Where do Ringo’s quirks come from, according to Ringo? “It has to do with swing,” he deadpans, “or as we keep mentioning, medication.” More seriously, he explains above in an interview with Conan O’Brien, he “leads with his left,” a limitation that he turned into a musical legacy on his favorite Beatles drum moments and on everyone else’s.

via Boing Boing

Related Content:

How Can You Tell a Good Drummer from a Bad Drummer?: Ringo Starr as Case Study

Isolated Drum Tracks From Six of Rock’s Greatest: Bonham, Moon, Peart, Copeland, Grohl & Starr

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Free Software Lets You Create Traditional Japanese Wood Joints & Furniture: Download Tsugite

The Japanese art of tsugite, or wood joinery, goes back more than a millennium. As still practiced today, it involves no nails, screws, or adhesives at all, yet it can be used to put up whole buildings — as well as to disassemble them with relative ease. The key is its canon of elaborately carved joints engineered to slide together without accidentally coming apart, the designs of which we’ve previously featured here on Open Culture in animated GIF form. Though it would be natural to assume that 21st-century technology has no purchase on this domain of dedicated traditional craftsmen, it does greatly assist the efforts of the rest of us to understand just how tsugite works.

Now, thanks to researchers at the University of Tokyo, a new piece of software makes it possible for us to do our own Japanese joinery as well. Called, simply, Tsugite, it’s described in the video introduction above as “an interactive computational system to design wooden joinery that can be fabricated using a three-axis CNC milling machine.” (CNC stands for “computer numerical control,” the term for a standard automated-machining process.)

In real time, Tsugite’s interface gives graphical feedback on the joint being designed, evaluating its overall “slidabilty” and highlighting problem areas, such as elements “perpendicular to the grain orientation” and thus more likely to break under pressure.

This is the sort of thing that a Japanese carpenter, having undergone years if not decades of training and apprenticeship, will know by instinct. And though the work of a three-axis CNC machine can’t yet match the aesthetic elegance of joinery hand-carved by a such a master, Tsugite could well, in the hands of users from different cultures as well as domains of art and craft, lead to the creation of new and unconventional kinds of joints as yet unimagined. You can download the software on Github, and you’ll also find supplementary documentation here. Even if you don’t have a milling system handy, working through virtual trial and error constitutes an education in traditional Japanese wood joinery by itself. The current version of Tsugite only accommodates single joints, but its potential for future expansion is clear: with practice, who among us wouldn’t want to try our hand at, say, building a shrine?

via Spoon & Tamago

Related Content:

See How Traditional Japanese Carpenters Can Build a Whole Building Using No Nails or Screws

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...A 4,000-Year-Old Student ‘Writing Board’ from Ancient Egypt (with Teacher’s Corrections in Red)

Americans raised on Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House books tend to associate slates with one room schoolhouses and rote exercises involving reading, writing and ‘rithmetic.

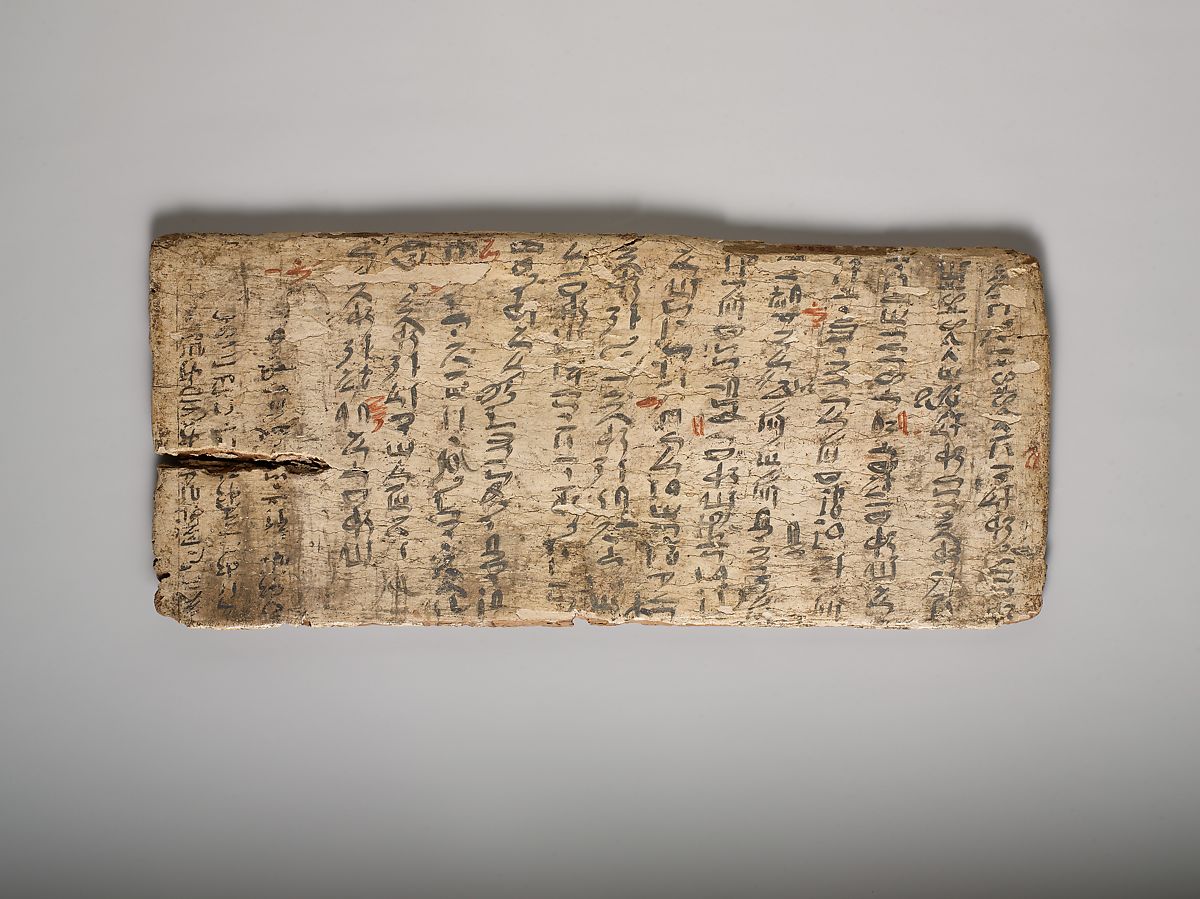

Had we been reared along the banks of the Nile, would our minds go to ancient gessoed boards like the 4000-year-old Middle Kingdom example above?

Like our familiar tablet-sized blackboards, this paper — or should we say papyrus? — saver was designed to be used again and again, with whitewash serving as a form of eraser.

As Egyptologist William C. Hayes, former Curator of Egyptian Art at the Metropolitan Museum wrote in The Scepter of Egypt: A Background for the Study of the Egyptian Antiquities in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vol. 1, From the Earliest Times to the End of the Middle Kingdom, the writing board at the top of the page:

…bears parts of two model letters of the very formal and ultra-poite variety addressed to a superior official. The writers consistently refer to themselves as “this servant” and to their addressees as “the Master (may he live, prosper, and be well.)” The longer letter was composed and written by a young man named Iny-su, son of Sekhsekh, who calls himself a “Servant of the Estate” and who, probably in jest, has used the name of his own brother, Peh-ny-su, as that of the distinguished addressee. Following a long-winded preamble, in which the gods of Thebes and adjacent towns are invoked in behalf of the recipient, we get down to the text of the letter and find that it concerns the delivery of various parts of a ship, probably a sacred barque. In spite of its formality and fine phraseology, the letter is riddled with misspellings and other mistakes which have been corrected in red ink, probably by the master scribe in charge of the class.

Iny-su would also have been expected to memorize the text he had copied out, a practice that carried forward to our one-room-schoolhouses, where children droned their way through texts from McGuffey’s Eclectic Readers.

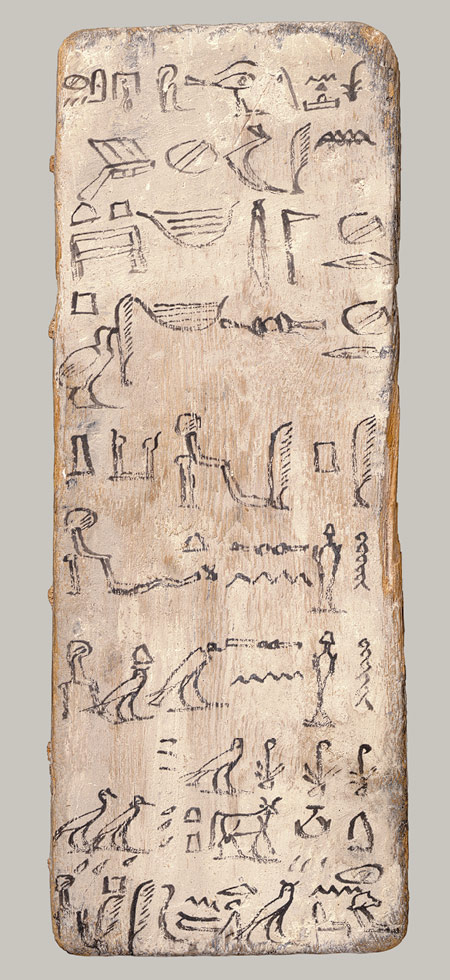

Another ancient Egyptian writing board in the Met’s collection finds an apprentice scribe fumbling with imperfectly formed, unevenly spaced hieroglyphs.

Fetch the whitewash and say it with me, class — practice makes perfect.

The first tablet inspired some lively discussion and more than a few punchlines on Reddit, where commenter The-Lord-Moccasin mused:

I remember reading somewhere that Egyptian students were taught to write by transcribing stories of the awful lives of the average peasants, to motivate and make them appreciate their education. Like “the farmer toils all day in the burning field, and prays he doesn’t feed the lions; the fisherman sits in fear on his boat as the crocodile lurks below.”

Always thought it sounded effective as hell.

We can’t verify it, but we second that emotion.

Note: The red markings on the image up top indicate where spelling mistakes were corrected by a teacher.

via @ddoniolvalcroze

Related Content:

What Ancient Egyptian Sounded Like & How We Know It

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

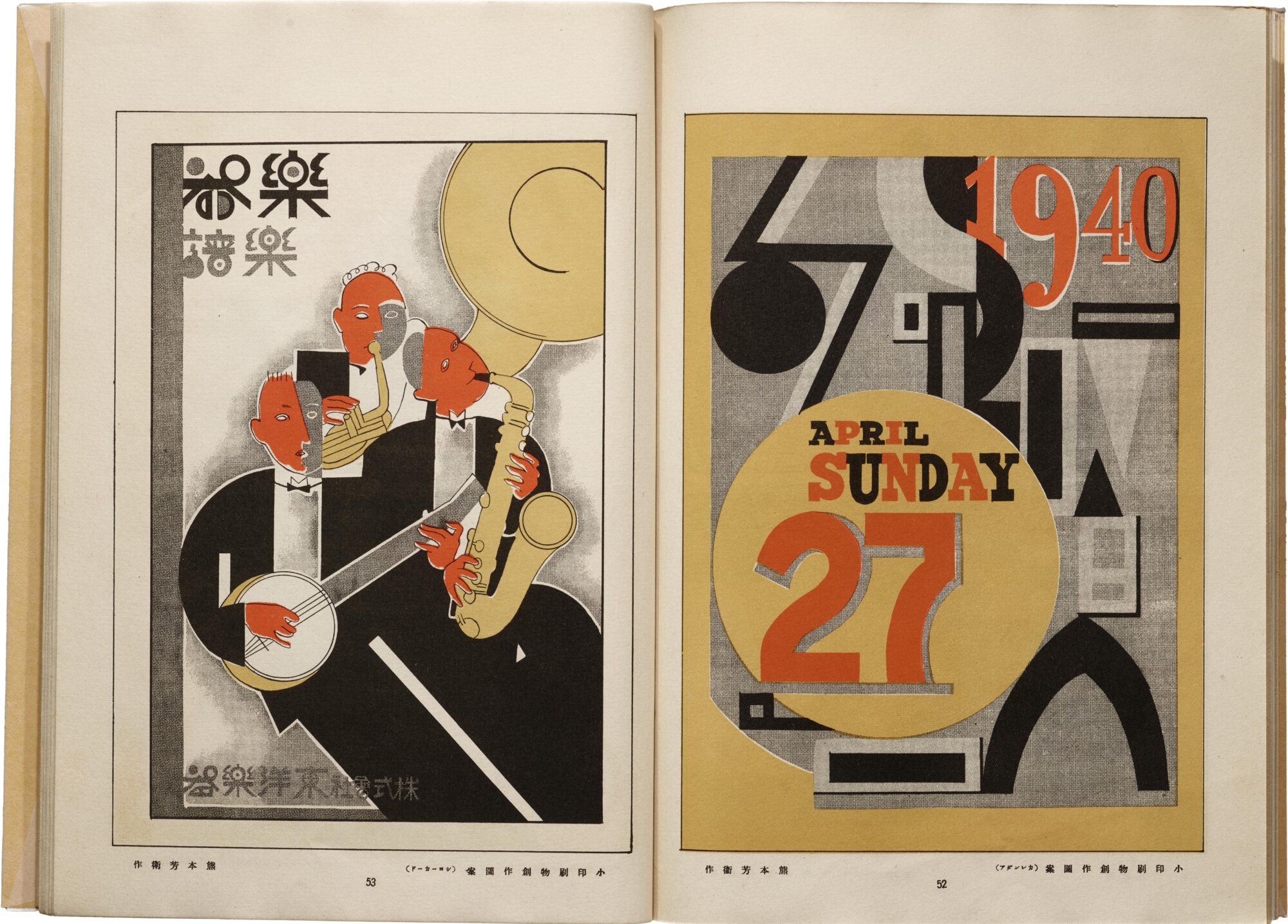

Read More...The Letterform Archive Launches a New Online Archive of Graphic Design, Featuring 9,000 Hi-Fi Images

An online design museum made by and for designers? The concept seems obvious, but has taken decades in internet years for the reality to fully emerge in the Letterform Archive. Now that it has, we can see why. Good design may look simple, but no one should be fooled into thinking it’s easy. “After years of development and months of feedback,” write the creators of the Letterform Archive online design museum, “we’re opening up the Online Archive to everyone. This project is a labor of love from everyone on our staff, and many generous volunteers, and we hope it provides a source of beautiful distraction and inspiration to all who love letters.”

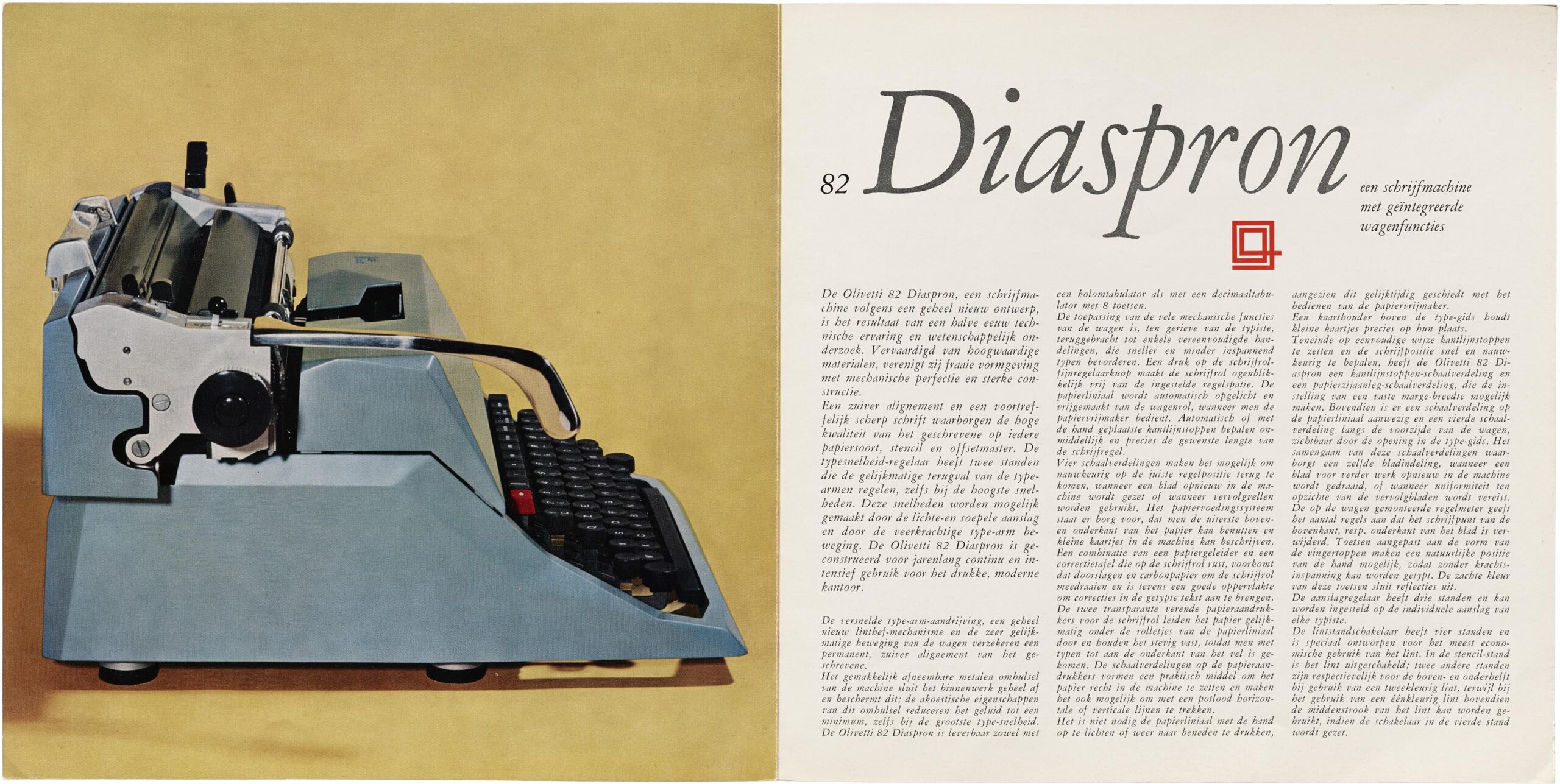

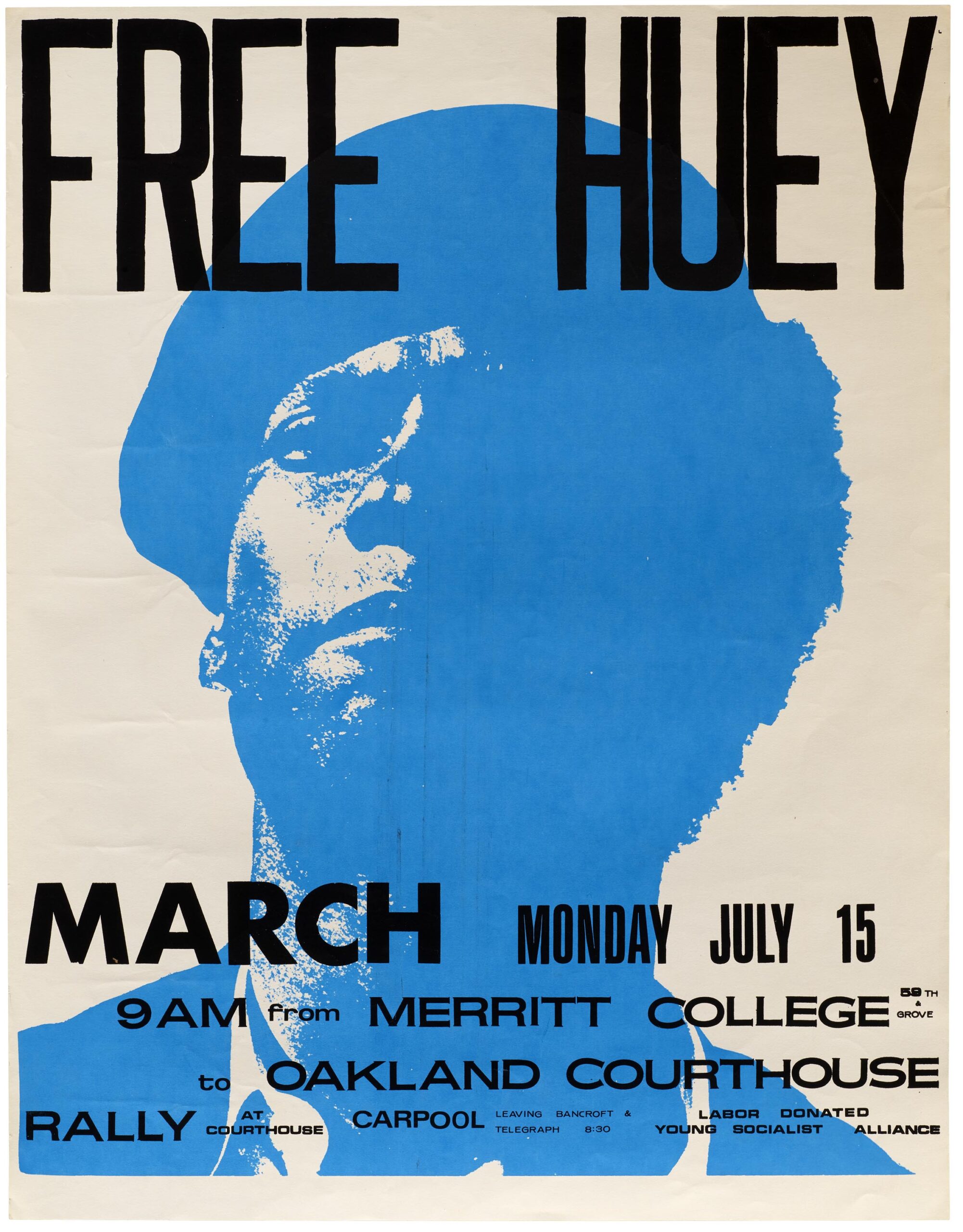

That’s letters as in fonts, not epistles, and there are thousands of them in the archive. But there are also thousands of photographs, lithographs, silkscreens, etc. representing the height of modern simplicity. This and other unifying threads run through the collection of the Letterform Archive, which offers “unprecedented access… with nearly 1,500 objects and 9,000 hi-fi images.”

You’ll find in the Archive the sleek elegance of 1960s Olivetti catalogs, the iconic militancy of Emory Douglas’ designs for The Black Panther newspaper, and the eerily stark militancy of the “SILENCE=DEATH” t‑shirt from the 1980s AIDS crisis.

The site was built around the ideal of “radical accessibility,” with the aim of capturing “a sense of what it’s like to visit the Archive” (which lives permanently in San Francisco). But the focus is not on the casual onlooker — Letterform Archive online caters specifically to graphic designers, which makes its interface even simpler, more elegant, and easier to use for everyone, coincidentally (or not).

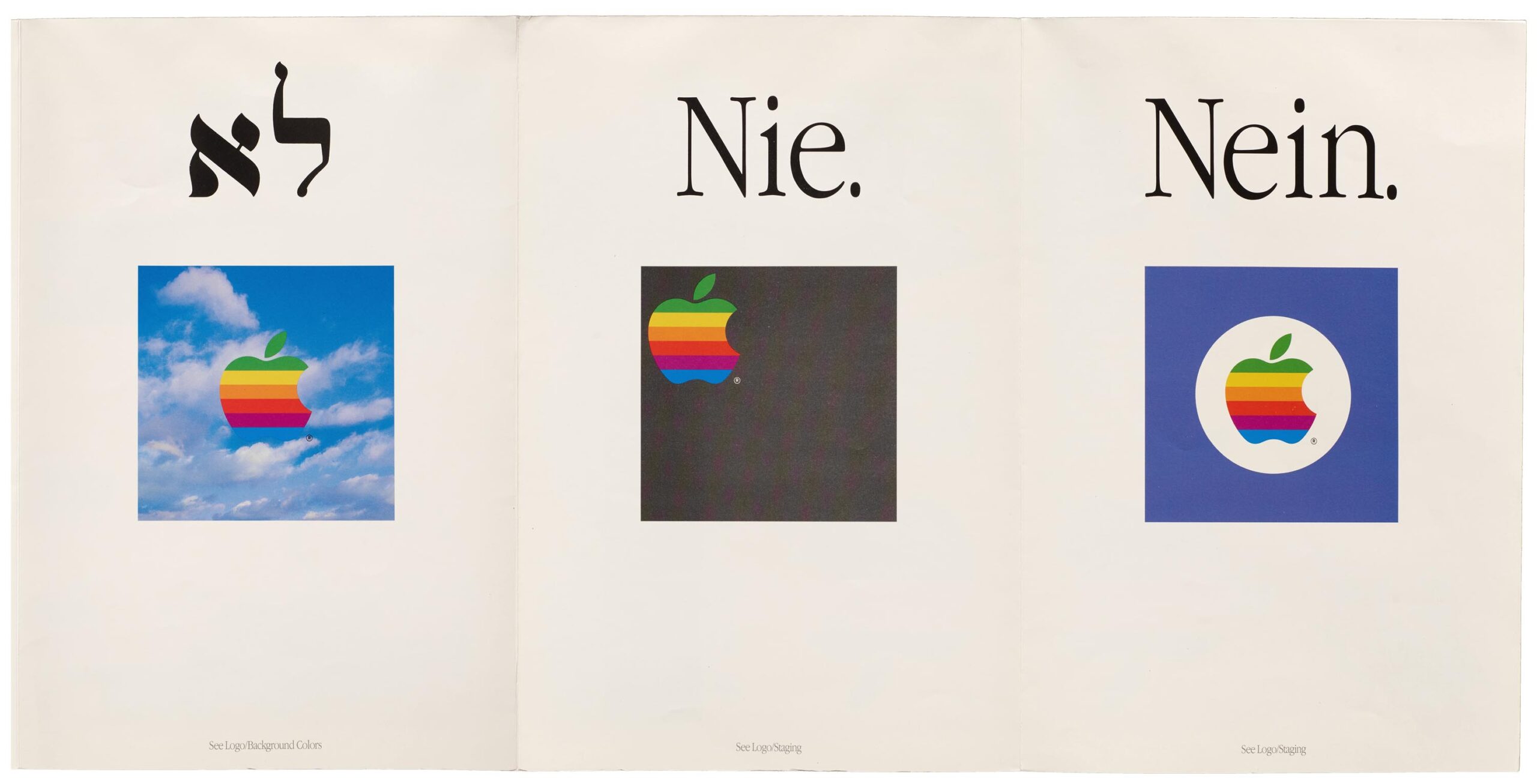

The graphic design focus also means there are functions specific to the discipline that designers won’t find in other online image libraries: “we encourage you to use the search filters: click on each category to explore disciplines like lettering, and formats like type specimens, or combine filters like decades and countries to narrow your view to a specific time and place.”

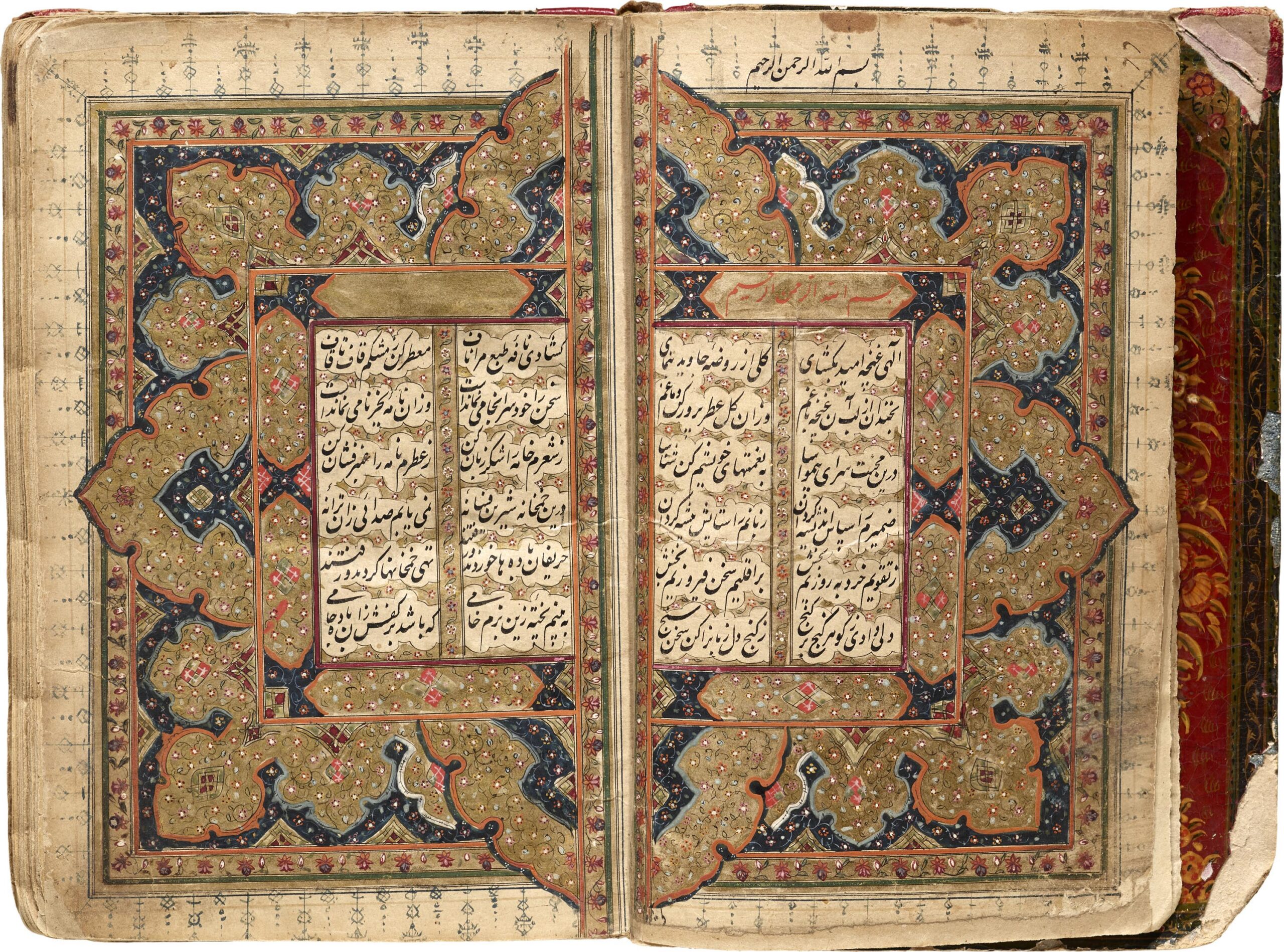

From the radical typography of Dada to the radical 60s zine scene to the sleek designs (and Neins) found in a 1987 Apple Logo Standards pamphlet, the museum has something for everyone interested in recent graphic design history and typology. But it’s not all sleek simplicity. There are also rare artifacts of elaborately intricate design, like the Persian Yusef and Zulaikha manuscript, below, dating from between 1880 and 1910. You’ll find dozens more such treasures in the Letterform Archive here.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Women Street Photographers: The Web Site, Instragram Account & Book That Amplify the Work of Women Artists Worldwide

It’s almost impossible not to wonder how reclusive artists of the past — like anonymous street photographer and Chicago nanny Vivian Maier — would fare in the age of Tumblr and Instagram. Would Maier have become internet famous? Would she have posted any of her photographs? The little we know about her makes it hard to answer the question. Maier lived a life of abstemious self-negation. “She never exhibited her work,” Alex Kotlowitz writes at Mother Jones, “she didn’t share her photos with anyone, except some of the children in her care.”

And yet, Maier was known to enjoy conversations about film and theater with knowledgeable people. One suspects that if she had been able to stay in touch with like minds, she might have been encouraged by a supportive community she couldn’t find anywhere else. We might imagine her, for example, submitting a select few photographs to Women Street Photographers, a project that began in 2017 as an Instagram account and has since “burgeoned into a website, artist residency, series of exhibitions, film series, and now a book published this month by Prestel,” Grace Ebert writes at Colossal.

For women street photographers living and working today, the project offers what founder Gulnara Samoilova says she needed and couldn’t find: “I soon began to realize that with this platform, I could create everything I had always wanted to receive as a photographer: the kinds of support and opportunities that would have helped me grow during those formative and pivotal points on my journey.” The project is international in scope, bringing together the work of 100 women from 31 countries, “a tiny sampling of what’s out there.”

In her introduction to the 224-page book, Samoilova describes the importance of such a collection:

Street photography is both a record of the world and a statement of the artist themselves: it is how they see the world, who they are, what captures their attention, and fascinates them. There’s a wonderful mixture of art and artifact, poetry and testimony that makes street photography so appealing. It’s both documentary and fine art at the same time, yet highly accessible to people outside the photography world.

There are Vivian Maiers around the world driven to document their surroundings, whether anyone ever sees their work or not. Maier made her photographs “for all the right reasons,” says Chicago artist Tony Fitzpatrick. “She made them because to not make them was impossible. She had no choice.” But perhaps she might have chosen to show her work if she had access to platforms like Women Street Photographers. We can be grateful for such outlets now: they offer perspectives that we can find nowhere else. Women Street Photographers will announce the winners of its inaugural virtual exhibition “on or around April 1.”

via Colossal

Related Content:

Meet Gerda Taro, the First Female Photojournalist to Die on the Front Lines

Take a Visual Journey Through 181 Years of Street Photography (1838–2019)

Vivian Maier, Street Photographer, Discovered

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

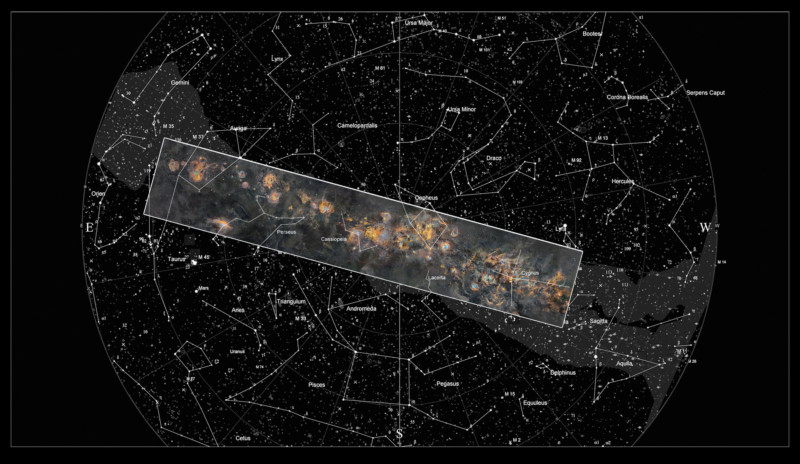

Read More...A Finnish Astrophotographer Spent 12 Years Creating a 1.7 Gigapixel Panoramic Photo of the Entire Milky Way

In the final, climactic scene of Japanese novelist Yasunari Kawabata’s Snow Country, the Milky Way engulfs the protagonist — an aesthete who keeps himself detached from the world, a universal perspective overtaking an insignificant individual.

We now know the Milky Way itself to be a minuscule part of the whole, just one of 100 to 200 billion galaxies. But until Edwin Hubble’s observations in 1924, it was thought to contain all the stars in existence.

The Milky Way-as-universe is a powerful image, and certainly more comprehensible than the universe as astronomers currently understand it. Its vastness can’t be compressed into a symbolic form like the via lactea, “Milky Way,” or as the Greeks called it, galaktikos kýklos, “milky circle.” Andy Briggs summarizes just a few of the ancient myths and legends:

To the ancient Armenians, it was straw strewn across the sky by the god Vahagn. In eastern Asia, it was the Silvery River of Heaven. The Finns and Estonians saw it as the Pathway of the Birds.… Both the Greeks and the Romans saw the starry band as a river of milk. The Greek myth said it was milk from the breast of the goddess Hera, divine wife of Zeus. The Romans saw the river of light as milk from their goddess Ops.

A barred spiral galaxy spinning around a “galactic bulge” with an empty center, a “monstrous black hole,” notes Space.com, “billions of times as massive as the sun”… the Milky Way remains an awesome symbol for a universe too vast for us to hold in our minds.

Witness, for example, the just-released image further up, a 1.7 gigapixel panoramic photo of the Milky Way, from Taurus to Cygnus, 100,000 pixels wide, pieced together from 234 panels by Finnish astrophotographer J‑P Metsavainio, who began the project all the way back in 2009. “I can hear music in this composition,” he writes at his site, “from high sparks and bubbles at left to deep and massive sounds at right.”

Over 12 years, and around 1250 hours of exposure, Michael Zhang writes at Petapixel, Metsavainio “focused on different areas and objects in the Milky Way, shooting stitched mosaics of them as individual artworks.” As he began to knit the galactic clouds of stars and gasses together into a Photoshop panorama, he discovered a “complex image set which is partly overlapping with lots of unimaged areas between and around frames.” Over the years, he filled in the gaps, shooting the “missing data.” He describes his equipment and process in detail, for those fluent in the technical jargon. The rest of us can stare in silent wonder at more of Metsavainio’s work on his website (where you can also purchase prints) and Facebook, and let ourselves be overtaken by awe.

via Petapixel and Kottke

Related Content:

How Scientists Colorize Those Beautiful Space Photos Taken By the Hubble Space Telescope

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...What are Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs)? And How Can a Work of Digital Art Sell for $69 Million

Value in the art world depends on manufactured desire for objects that serve no purpose and have no intrinsic meaning outside of the stories that surround them, which is why it can be easy to fool others with fraudulent copies. Collectors and experts are often eager to believe a well-told tale of special provenance. As Orson Welles says in F is for Fake, “Lots of oysters, only a few pearls. Rarity. The chief cause and encouragement of fakery and phoniness.”

“Concepts of fakery and originality bounce off one another as reflections,” Lidija Grozdanic writes of Welles’ documentary on “our innate infatuation with exclusivity,” a film made when the internet consisted of 36 routers and 42 host computers — in total (including a link in Hawaii!). Now we are immersed in hyperreality. Copies of digital artworks are indistinguishable from each other, since they cannot be said to exist in any material sense. How can they be authenticated? How can they become exclusive placeholders for wealth?

The questions have been taken up, and answered rather abruptly, it seems, by the architects of blockchain technology, who bring us NFTs, or “Non-Fungible Tokens,” an acronym and phraseology you’ve surely heard, whether you’ve felt inclined to learn what they mean. The videos featured today offer brief explanations, by reference especially to the case of South Carolina-based digital artist named Mike Winklemann, who goes by Beeple, and who first harnessed the power of NFTs to make millions.

Most recently, in a first-of-its-kind online auction at Christies, Beeple’s montage “‘Everydays — The First 5000 Days’… became the ‘What Does the Fox Say?’ of art sales,” writes Erin Griffiths at The New York Times.

A crypto whale known only by the pseudonym Metakovan paid $69 million (with fees) for some indiscriminately collated pictures of cartoon monsters, gross-out gags and a breastfeeding Donald Trump — which suddenly makes this computer illustrator the third-highest-selling artist alive.

The criticism is perhaps unfair. As Christies argues in its defense, the piece reveals “Beeple’s enormous evolution as an artist” over five years. Specialist Noah Davis calls the collage, stitched together from Beeple’s body of work on Instagram, “a kind of Duchampian readymade.” But it doesn’t really matter if Beeple’s work is avant-garde high art.

The libertarian econo-speak “nonfungible token” reveals itself as part of a world divorced from the usual criteria art historians, curators, auction houses, and others apply in their judgments of authenticity and worth. Instead, the value of NFTs rests mainly on the fact that they are exclusive, without particularly high regard for what they include. One may love the work of Beeple, but we should be clear, “what Christie’s sold was not an object” — there is no object — “but a ‘nonfungible token,’” which is “bitcoinese for unique string of characters, logged on a blockchain,” that cannot be exchanged or replaced… like owning a Monet without owning a Monet.

Unlike the Wu Tang album Once Upon a Time in Shaolin, bought for $2 million in 2015 by Martin Shkreli, content attached to NFTs can be shared, viewed, copied, etc. over and over. “Millions of people have seen Beeple’s art,” the BBC explains, “and the image has been copied and shared countless times. In many cases, the artist even retains the copyright ownership of their work, so they can continue to produce and sell copies.”

Other sales of NFTs include a version of the 10-year-old internet meme Nyan Cat that sold for $600,000, a clip of LeBon James blocking a shot for $100,000, and a picture of Lindsay Lohan for $17,000, which then resold for $57,000. Lohan articulated the NFT ethos in a statement, saying, “I believe in a world which is financially decentralized.” This is not a world where judgments about the value of art and culture can be centralized either. But power can be, presumably, in the form of currency, crypto-and otherwise, traded in speculative bubbles.

“Some people compare it to buying an autographed print,” the BBC writes. Some compare it to the age-old scams warned of in folk tales. David Gerard, author of Attack of the 50 Foot Blockchain, calls NFT sellers “crypto-grifters… the same guys who’ve always been at it, trying to come up with a new form of worthless bean that they can sell for money.” This eternal scam exists beyond the binaries posed by F is for Fake. Originality, authenticity, or otherwise are mostly beside the point.

Related Content:

The Art Market Demystified in Four Short Documentaries

Warhol: The Bellwether of the Art Market

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

Read More...Yo-Yo Ma Plays an Impromptu Performance in Vaccine Clinic After Receiving 2nd Dose

After getting his second dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, Yo-Yo Ma “took a seat along the wall of the observation area, masked and socially distanced away from the others. He went on to pass 15 minutes in observation playing cello for an applauding audience,” writes the Berkshire Eagle. You can watch the scene above, which played out at Berkshire Community College this weekend. And read more about it here.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

How Do Vaccines (Including the COVID-19 Vaccines) Work?: Watch Animated Introductions

MIT Presents a Free Course on the COVID-19 Pandemic, Featuring Anthony Fauci & Other Experts

Read More...

Rare Vincent van Gogh Painting Goes on Public Display for the First Time: Explore the 1887 Painting Online

Images courtesy of Sothebys

Not every Vincent van Gogh painting hangs at the Van Gogh Museum, or indeed in a museum at all. Though many private collectors loan their Van Goghs to art institutions that make them available for public viewing, some have never let such prized possessions out of their sight. Such, until recently, was the case with Scène de rue à Montmartre (Impasse des Deux Frères et le Moulin à Poivre), painted in 1887 but not shown to the world until this year — in preparation for its auction on March 25. During its century of possession by a single French family, the painting counted as one of the few privately-held entries in Van Gogh’s Montmartre series, which he painted in the eponymous neighborhood during the two years spent in Paris with his brother Theo.

“Unlike other artists of his era, like Toulouse-Lautrec, Van Gogh was attracted to the pastoral side of Montmartre and would transcribe this ambience rather than its balls and cabarets.” So says Aurélie Vandevoorde, head of the Impressionist and Modern Art department at Sotheby’s Paris to The Art Newspaper’s Anna Sanson.

The landscape “marks van Gogh’s turn to his distinctive Impressionist style,” writes Colossal’s Grace Ebert, and its “lively street is thought to be the same as that in Impasse des Deux Frères, which currently hangs at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, and similarly depicts a mill and flags promoting the cabaret and bar through the gates.”

As depicted by Van Gogh more than 130 years ago, Montmartre looks nearly rural — quite unlike it does now, as anyone who’s frequented the neighborhood in living memory can attest. But the status of the painting has changed even more than the status of the place: Scène de rue à Montmartre “is expected to sell for between $6 million and $9.7 million (€5 million to €8 million),” writes Smithsonian.com’s Isis Davis-Marks. Still, like most of Van Gogh’s Paris paintings, its value doesn’t touch that of the work he did in his subsequent Provençal sojourn (under the influence of Japanese ukiyo‑e). “One such painting, Laboureur dans un champ (1889),” adds Davis-Marks, “sold at Christie’s in 2017 for $81.3 million.” Well-heeled readers should thus keep an eye on Sotheby’s site: this could be your chance to keep a (relatively) affordable Van Gogh in your own family for the next century.

via Colossal

Related Content:

Van Gogh’s Ugliest Masterpiece: A Break Down of His Late, Great Painting, The Night Café (1888)

13 Van Gogh’s Paintings Painstakingly Brought to Life with 3D Animation & Visual Mapping

Experience the Van Gogh Museum in 4K Resolution: A Video Tour in Seven Parts

In a Brilliant Light: Van Gogh in Arles – A Free Documentary

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Saturday Night Live’s Very First Sketch: Watch John Belushi Launch SNL in October, 1975

How do you kick off the longest running live sketch comedy show in television history? If you’re in the cast and crew for the first episode of Saturday Night Live, you have no idea you’re doing anything of the kind. Still the pressure’s on, and the newly hired “Not Ready for Primetime Players” had a lot of competition on their own show that night. When Saturday Night, the original title for SNL, made its debut on October 11, 1975, doing live comedy on television was an extremely risky proposition.

So, what do you do if you’re producers Dick Ebersol and Lorne Michaels? Put your riskiest foot forward — John Belushi, the “first rock & roll star of comedy” writes Rolling Stone, and “the ‘live’ in Saturday Night Live.” The man who would be comedy’s king, for a time, before he left the stage too soon. His first sketch, and the first on-air for SNL, reveals “a tendency toward the timelessly peculiar,” Time magazine writes, that made the show an instant cult hit.

Rather than skewering topical issues or impersonating celebrities, the first sketch, “The Wolverines” goes after the ripe targets of an immigrant (Belushi) learning English and his teacher, played by head writer Michael O’Donoghue, who insists on making Belushi repeat the titular word in nonsensical phrases like “I would like to feed your fingertips to the wolverines.”

Belushi’s accent has shades of Andy Kaufman’s “foreign man” from Caspiar, and he gets a brief moment to display his physical comedy skills when he keels over in imitation of his teacher having a heart attack. “The Wolverines” is short, nonsensical, and weirdly sweet. “No one would know what kind of show this was from seeing that,” Michaels remembered. We can still look back at that wildly uneven first season and wonder what kind of show SNL would be now if it had held on to the anarchic spirit of the early years. But that’s a lot to ask of a 45-year-old live comedy show.

The night’s guest was George Carlin, who did not appear in any sketches, but who did get three separate monologues. The show also featured two musical guests, Billy Preston and Janis Ian. Andy Kaufman made an appearance doing his famous Mighty Mouse bit, and the Muppets were there (not the fun Muppets, but a “dark and grumpy version” Jim Henson disowned after the first season.)

The first episode was also the first to feature the iconic intro, “Live from New York, it’s Saturday Night!” — delivered by Chevy Chase. Though it has become a celebratory announcement, at the time “it’s Saturday Night!” was a dark reminder of the live comedy variety show, Saturday Night Live with Howard Cosell, then failing through its first and only season before its 18-episode run came to an end the following year.

See more from that weird first night above, including Carlin’s Football and Baseball monologue and the forgotten SNL Muppets, just above.

Related Content:

Classic Punk Rock Sketches from Saturday Night Live, Courtesy of Fred Armisen

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...