The Joy of Painting with Bob Ross & Banksy: Watch Banksy Paint a Mural on the Jail That Once Housed Oscar Wilde

It would be difficult to think of two artists who appear to have less in common than Bob Ross and Banksy. One of them creates art by pulling provocative stunts, often illegal, under the cover of anonymity; the other did it by painting innocuous landscapes on public television, spending a decade as one of its most recognizable personalities. But game recognize game, as they say, in popular art as in other fields of human endeavor. In the video above, Banksy pays tribute to Ross by layering narration from an episode of The Joy of Painting over the creation of his latest spray paint strike, Create Escape: an image of Oscar Wilde, typewriter and all, breaking out jail — on the actual exterior wall of the decommissioned HM Prison Reading.

“The expansive and unblemished prison wall was a daring and perfect spot for a Banksy piece,” writes Colossal’s Christopher Jobson. “It’s best known for its most famous inmate: Oscar Wilde served two years in the prison from 1895–1897 for the charge of ‘gross indecency’ for being gay.” This experience resulted in the poem The Ballad of Reading Gaol, which we’ve previously featured here on Open Culture as read by Wilde himself.

Where Wilde converted his misfortune into verbal art, Banksy references it to make a visual statement of characteristic brazenness and ambiguity. As with most of his recent pieces, Create Escape has clearly been designed to be seen not just by passersby in Reading, but by the whole world online, which The Joy of Painting with Bob Ross & Banksy should ensure.

“I thought we’d just do a very warm little scene that makes you feel good,” says Ross in voiceover. But what we see are the hands of a miner’s-helmeted Banksy, presumably, preparing his spray cans and putting up his stencil of Wilde in an inmate’s uniform. “Little bit of white,” says Ross as a streak of that color is applied to the prison wall. “That ought to lighten it just a little.” In fact, every sample of Ross’ narration reflects the action, as when he urges thought “about shape and form and how you want the limbs to look,” or when he tells us that “a nice light area between the darks, it separates, makes everything really stand out and look good.” With his signature high-contrast style, Banksy could hardly deny it, and he would seem also to share Ross’ feeling that in painting, “I can create the kind of world that I want to see, and that I want to be part of.”

Related Content:

Experience the Bob Ross Experience: A New Museum Open in the TV Painter’s Former Studio Home

Banksy Strikes Again in London & Urges Everyone to Wear Masks

Banksy Debuts His COVID-19 Art Project: Good to See That He Has TP at Home

Hear Oscar Wilde Recite a Section of The Ballad of Reading Gaol (1897)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Witness the Birth of Kermit the Frog in Jim Henson’s Live TV Show, Sam and Friends (1955)

Long before “green” became synonymous with eco-friendly products and production, an 18-year-old Jim Henson created a puppet who would go on to become the color’s most celebrated face from his mother’s cast-off green felt coat and a single ping pong ball.

Kermit debuted in black and white in the spring of 1955 as an ensemble member of Sam and Friends, a live television show comprised of five-minute episodes that the talented Henson had been tapped to write and perform, following some earlier success as a teen puppeteer.

Airing on the Washington DC-area NBC affiliate between the evening news and The Tonight Show, Sam and Friends was an immediate hit with viewers, even if they ranked Kermit, originally more lizard than frog, fourth in terms of popularity. (Top spot went to a skull puppet named Yorick.)

Watching the surviving clips of Sam and Friends, it’s easy to catch glimpses of where both Kermit and Henson were headed.

While Henson voiced Sam and all of his puppet friends, Kermit wound up sounding the closest to Henson himself.

Kermit’s signature face-crumpling reactions were by design. Whereas other puppets of the period, like the titular Sam, had stiff heads with the occasional moving jaw, Kermit’s was as soft as a footless sock, allowing for far greater expressiveness.

Henson honed Kermit’s expressions by placing live feed monitors on the floor so he and his puppeteer bride-to-be Jane, could see the puppets from the audience perspective.

Unlike previously televised puppet performances, which preserved the existing prosceniums of the theaters to which the players had always been confined, Henson considered the TV set frame enough. Liberating the puppets thusly gave more of a sketch comedy feel to the proceedings, something that would carry over to Sesame Street and later, The Muppet Show.

By the 12th episode, Kermit has found a niche as wry straight man for wackier characters like jazz aficionado Harry the Hipster who introduced an element of musical notation to the animated letters and numbers that would become a Sesame Street staple.

And surely we’re not the only ones who think the Muppets’ recent appearance in a Super Bowl ad pales in comparison to Kermit and Harry’s live commercial for Sam and Friends’ sponsor, a regional brand of bacon and lunch meat.

Sam and Friends ran from 1955 to 1961, but Kermit’s first performance on The Tonight Show in 1956, lip syncing to Rosemary Clooney’s recording of “I’ve Grown Accustomed to Your Face” and mugging in a blonde braided wig, hinted that he and Henson would soon outgrow the local television pond.

Related Content:

Jim Henson Creates an Experimental Animation Explaining How We Get Ideas (1966)

The Creative Life of Jim Henson Explored in a Six-Part Documentary Series

Watch The Surreal 1960s Films and Commercials of Jim Henson

Jim Henson Teaches You How to Make Puppets in Vintage Primer From 1969

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine, current issue #63. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...Take a Road Trip Across America with Cartoonist Lynda Barry in the 90s Documentary, Grandma’s Way Out Party

Who wouldn’t love to take a road trip with beloved cartoonist and educator Lynda Barry? As evidenced by Grandma’s Way Out Party, above, an early-90s documentary made for Twin Cities Public Television, Barry not only finds the humor in every situation, she’s always up for a detour, whether to a time honored destination like Mount Rushmore or Old Faithful, or a more impulsive pitstop, like a Washington state car repair shop decorated with sculptures made from cast off mufflers or the Montana State Prison Hobby Store.

Alternating in the driver’s seat with then-boyfriend, storyteller Kevin Kling, she makes up songs on her accordion, clowns around in a cheap cowgirl hat, samples an oversized gas station donut, and chats up everyone she encounters.

At the World’s Only Corn Palace in Mitchell, South Dakota, she breaks the ice by asking a bearded local guy in official Corn Palace cap and t‑shirt if his job is the fulfillment of a long held dream.

“Nah,” he says. “I thought it was a joke … in Fargo, they call it the world’s biggest bird feeder. We do have the biggest birds in South Dakota. They get fed good.”

He leads them to Cal Schultz, the art teacher who designed over 25 years worth of murals festooning the exterior walls. Nudged by Barry to pick a favorite, Schultz chooses one that his 9th grade students worked on.

“I would have loved to have been in his class,” Barry, a teacher now herself, says emphatically. “I would have given anything to have worked on a Corn Palace when I was 14-years-old.”

This point is driven home with a quick view of her best known creation, the pigtailed, bespectacled Marlys, ostensibly rendered in corn—an honor Marlys would no doubt appreciate.

Barry has long been lauded for her understanding of and respect for children’s inner lives, and we see this natural affinity in action when she befriends Desmond and Jake, two young participants in the Crow Fair Pow Wow, just south of Billings, Montana.

Frustrated by her inability to get a handle on the proceedings (“Why didn’t I learn it in school!? Why wasn’t it part of our curriculum?”), Barry retreats to the comfort of her sketchbook, which attracts the curious boys. Eventually, she draws their portraits to give them as keepsakes, getting to know them better in the process.

The drawings they make in return are treasured by the recipient, not least for the window they provide on the culture with which they are so casually familiar.

Barry and Kling also chance upon the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally, and after a bite at the Road Kill Cafe (“from your grill to ours”), Barry waxes philosophical about the then-unusual sight of so much tattooed flesh:

There’s something about the fact that they want something on them that they can’t wash off, that even on days when they don’t want people to know they’re a biker, it’s still there. And I have always loved that about people, like …drag queens who will shave off their eyebrows so they can draw perfect eyebrows on, or anybody who knows they’re different and does something to themselves physically so that even on their bad days, they can’t deny it. Because I think that in the end, that’s sort of what saves your life, that you wear your colors. You can’t help it.

The aforementioned muffler store prompts some musings that will be very familiar to anyone who has immersed themselves in Making Comics, Picture This, or any other of Barry’s instructional books containing her wonderfully loopy, intuitive creative exercises:

I think this urge to create is actually our animal instinct. And what’s sad is if we don’t let that come through us, I don’t think we have a full life on this earth. And I think we get sick because of it. I mean, it’s weird that it’s an instinct, but it’s an option, just like you can take a wild animal, a beautiful, wild animal and put him in a zoo. They live, they’re fine in their cage, but you don’t get to see them do the thing that a cheetah does best, which is, you know, just run like the wind and be able to jump and do the things… I mean, it’s our instinct, it’s instinctual, it’s our beautiful, beautiful, magical, poetic, mysterious instinct. And every once in a while, you see the flower of it come right up out of a gas station.

After 1653 miles and one squabble after overshooting a scheduled stop (“You don’t want me to go to Butte!”), the two arrive at their final destination, Barry’s childhood home in Seattle. The occasion? Barry’s Filipino grandmother’s 83rd birthday, and plans are afoot for a potluck bash at the local VFW hall. Fans will swoon to meet this venerated lady and the rest of Barry’s extended clan, and hear Barry’s reflections on what it was like to grow up in a working class neighborhood where most of the families were multi-racial.

“I walked in and it was everything Lynda said,” Kling marvels.

Indeed.

The journey is everything we could have hoped for, too.

Listen to a post-trip interview with Kling on Minnesota Public Radio.

H/t to reader Charlotte Booker

Related Content:

Cartoonist Lynda Barry Shows You How to Draw Batman in Her UW-Madison Course, “Making Comics”

Lynda Barry’s New Book Offers a Master Class in Making Comics

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine — current issue: #63 Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...How the Food We Eat Affects Our Brain: Learn About the “MIND Diet”

We humans did a number on ourselves, as they say, when we invented agriculture, global trade routes, refrigeration, pasteurization, and so forth. Yes, we made it so that millions of people around the world could have abundant food. We’ve also created food that’s full of empty calories and lacking in essential nutrients. Fortunately, in places where healthy alternatives are plentiful, attitudes toward food have changed, and nutrition has become a paramount concern.

“As a society, we are comfortable with the idea that we feed our bodies,” says neuroscientist Lisa Mosconi. We research foods that cause inflammation and increase cancer risk, etc. But we are “much less aware,” says Mosconi—author of Brain Food: The Surprising Science of Eating for Cognitive Power—“that we’re feeding our brains too. Parts of the foods we eat will end up being the very fabric of our brains…. Put simply: Everything in the brain that isn’t made by the brain itself is ‘imported’ from the food we eat.”

We learn much more about the constituents of brain matter in the animated TED-Ed lesson above by Mia Nacamulli. Amino acids, fats, proteins, traces of micronutrients, and glucose—“the brain is, of course, more than the sum of its nutritional parts, but each component does have a distinct impact on functioning, development, mood, and energy.” Post-meal blahs or insomnia can be closely correlated with diet.

What should we be eating for brain health? Luckily, current research falls well in line with what nutritionists and doctors have been suggesting we eat for overall health. Anne Linge, registered dietitian and certified diabetes care and education specialist at the Nutrition Clinic at the University of Washington Medical Center-Roosevelt, recommends what researchers have dubbed the MIND diet, a combination of the Mediterranean diet and the DASH diet.

“The Mediterranean diet focuses on lots of vegetables, fruits, nuts and heart-healthy oils,” Linge says. “When we talk about the DASH diet, the purpose is to stop high blood pressure, so we’re looking at more servings of fruits and vegetables, more fiber and less saturated fat.” The combination of the two, reports Angela Cabotaje at the University of Washington Medicine blog Right as Rain, results in a diet high in folate, carotenoids, vitamin E, flavonoids and antioxidants. “All of these things seem to have potential benefits to the cognitive function,” says Linge, who breaks MIND foods down into the 10 categories below:

Leafy greens (6x per week)

Vegetables (1x per day)

Nuts (5x per week)

Berries (2x per week)

Beans (3x per week)

Whole grains (3x per day)

Fish (1x per week)

Poultry (2x per week)

Olive oil (regular use)

Red wine (1x per day)

As you’ll note, red meat, dairy, sweets, and fried foods aren’t included: researchers recommend we consume these much less often. Harvard’s Healthbeat blog further breaks down some of these categories and includes tea and coffee, a welcome addition for people who prefer caffeinated beverages to alcohol.

“You might think of the MIND diet as a list of best practices,” says Linge. “You don’t have to follow every guideline, but wow, if how you eat can prevent or delay cognitive decline, what a fabulous thing.” It is, indeed. For a scholarly overview of the effects of nutrition on the brain, read the 2015 study on the MIND diet here and another, 2010 study on the critical importance of “brain foods” here.

Related Content:

How to Live to Be 100 and Beyond: 9 Diet & Lifestyle Tips

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Pussy Riot’s Nadya Tolokonnikova Tells Protestors What to Do–and Not Do–If Arrested by Authoritarian Police

Note: If the subtitles don’t play automatically, please click the “cc” at the bottom of the video.

Oligarchic regimes built on corruption and naked self-interest don’t typically exhibit much in the way of creativity when responding to crises of legitimacy. The most recent challenge to the oligarchic rule of Vladimir Putin, for example, after the attempted assassination and jailing of his rival, anti-corruption activist Alexey Navalny, revealed “the regime’s utter lack of imagination and inability to plan ahead,” writes Masha Gessen at The New Yorker, and seems to promise an opening for a revolutionary movement.

Perhaps it’s safer to say, Joshua Yaffa writes, “that Russian politics are merely entering the beginning of a protracted new phase,” that will involve more large, coordinated mass protests against the “perceived impunity and lawlessness of Putin’s system,” such as happened all over the country in recent days: “In St. Petersburg, a sizable crowd blocked Nevsky Prospekt, the city’s main thoroughfare. Several thousand gathered in Novosibirsk, the largest city in Siberia. Even in Yakutsk, a faraway regional capital, where the day’s temperatures reached minus fifty-eight degrees Fahrenheit, a number of people came out to the central square.”

Footage from the protests “shows activists pelting Russian riot police and vehicles with snowballs,” Dazed reports. Massive, in-real-life protests have been organized and supported by online activists on Tik Tok, YouTube, and other social media sites, where young people like viral teenager Neurolera share tips—such as pretending to be an indignant American—that might help protestors avoid arrest. In one video calling on young students to attend Saturday’s protests, a young woman holds a book, and captions “explain how she is reading about how citizens’ rights are guaranteed,” writes Brendan Cole at Newsweek. “But wait!” she says in one caption, “In Russia things happen differently.”

Russian citizens, and especially young activists, do not walk into protest situations unprepared for arrest and detention—particularly those who follow longtime trouble-makers Pussy Riot, famous for staging flamboyant anti-Putin protests and getting arrested. In the video at the top, the band/activist collective’s Nadya Tolokonnikova explains “how to behave when you’re arrested.” Detention “is an unpleasant experience,” she says, but it need not “end up being such a traumatic experience.” One must conquer fear with knowledge. During her first arrest, “I was scared because I felt that the police officers held an enormous power over me. That’s not true.”

The English translation seems inexact and many of the intricacies of Russian law will not translate to other national contexts. Woven throughout the video, however, are generally prudent tips—like not adding criminal charges by attacking police during arrest. Last year, the group distributed anti-surveillance make-up tips also useful to activists everywhere. The viral spread of videos like Pussy Riot’s and Neurolera’s tutorial show us a worldwide desire for youthful hope and determination in the face of brutal realities. Yaffa describes the “scenes of police employing brute force” that filled his Russian-language social media during the protests:

In one such video, from St. Petersburg, a woman confronts a column of riot policemen dragging a protester by his arms and asks, “Why are you arresting him?” One of the police officers kicks her in the chest, knocking her to the ground. Watching these scenes, I couldn’t help but think of Belarus, where months of street protests against the rule of Alexander Lukashenka have been marked by brutality and torture by the security forces, and a remarkable willingness from protesters to fight back against riot police, at times forcing them to retreat or abandon making an arrest.

These images do not spread so readily in English-language media, perhaps giving a superficial impression that the current anti-Putin, pro-Navalny movement is a new, young online phenomenon, rather than the continuation of a battle-hardened resistance to twenty years of misrule. “Throwing the book at Navalny could spark protests of undetermined strength and longevity,” Yaffa argues, from which mass movements around the world draw inspiration for years to come.

via Dazed

Related Content:

A History of Pussy Riot: Watch the Band’s Early Performances/Protests Against the Putin Regime

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

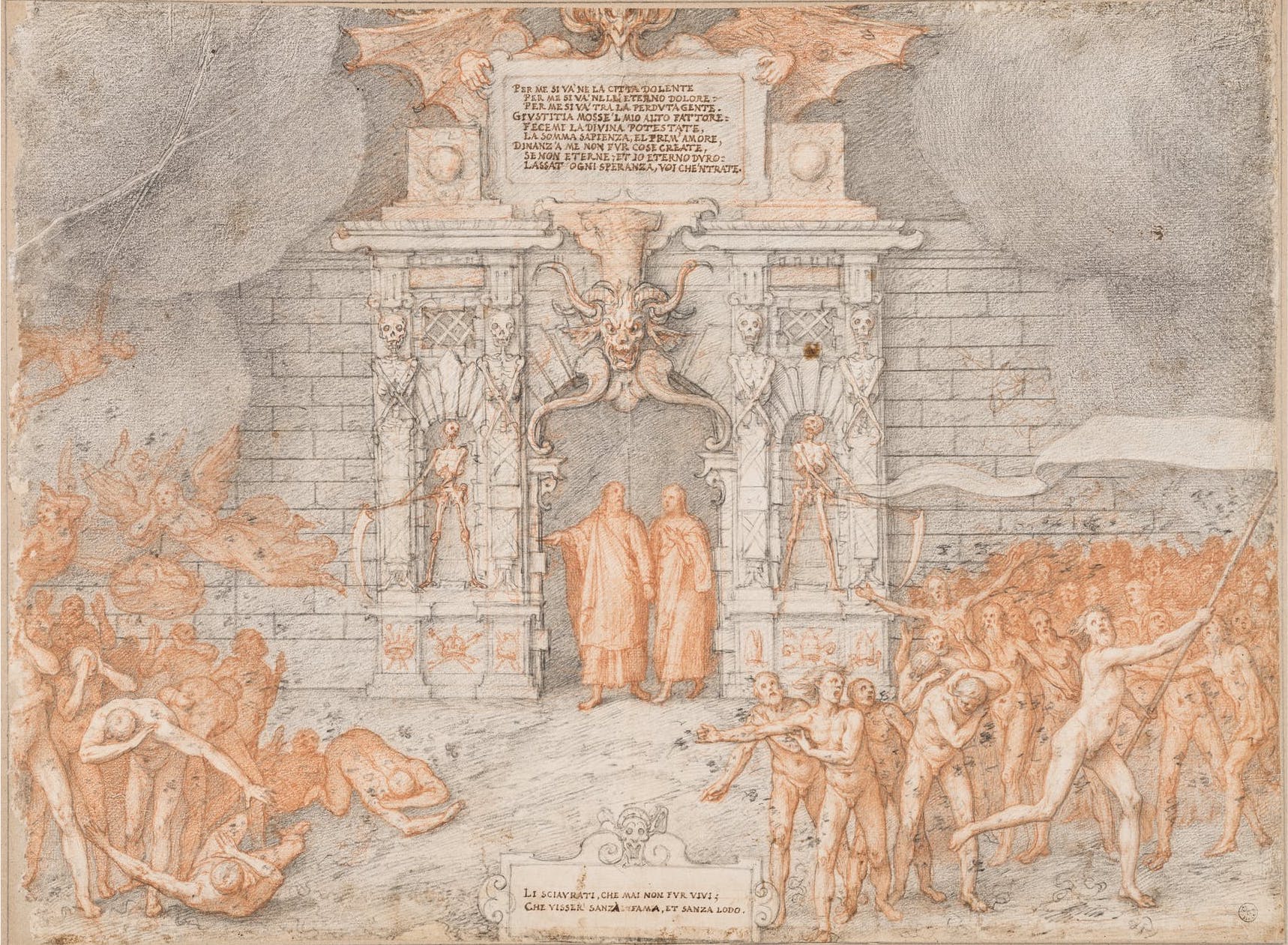

Read More...Rarely-Seen Illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy Are Now Free Online, Courtesy of the Uffizi Gallery

We know Dante’s Divine Comedy—especially its famous first third, Inferno—as an extended theological treatise, epic love poem, and vicious satire of church hypocrisy and the Florentine political faction that exiled Dante from the city of his birth in 1302. Most of us don’t know it the way its first readers did (and as Dante scholars do): a compendium in which “a number of medieval literary genres are digested and combined,” as Robert M. Durling writes in his translation of the Inferno.

These literary genres include vernacular traditions of romance poetry from Provence, popular long before Dante turned his Tuscan dialect into a literary language to rival Latin. They include “the dream-vision (exemplified by the Old French Romance of the Rose)”; “accounts of journeys to the Otherworld (such as the Visio Pauli, Saint Patrick’s Purgatory, the Navigatio Sancti Brendani)”; and Scholastic philosophical allegory, among other well-known forms of writing at the time.

By the time the Divine Comedy captured imaginations in the period of incunabula, or the infancy of the printed book, many of these associations and influences had receded. And by the time of the Counter-Reformation, the poem most impressed readers and illustrators of the text as a divine plan for a torture chamber and an encyclopedia of the tortures therein. Whatever other associations we have with Dante’s poem, we all know the nine circles of hell and have an ominous sense of what goes on there.

No doubt we also have in our mind’s eye some of the hundreds of illustrations made of the text’s gruesome depictions of hell, from Sandro Botticelli to Robert Rauschenberg. Illustrated editions of Dante’s poem began appearing in 1472, and the first fully illustrated edition in 1491. By the late 16th century, the poem had become a literary classic (the word Divine joined Comedy in the title in 1555). By this time, the tradition of depicting a literal, rather than a literary, hell was firmly established.

It was in this period that Frederico Zuccari made the beautiful illustrations you see here, completed, Angela Giuffrida writes at The Guardian, “during a stay in Spain between 1586 and 1588. Of the 88 illustrations, 28 are depictions of hell, 49 of purgatory and 11 of heaven. After Zuccari’s death in 1609, the drawings were held by the noble Orsini family, for whom the artist had worked, and later by the Medici family before becoming part of the Uffizi collection in 1738.”

The pencil-and-ink drawings have rarely been seen before because of their fragile condition. They were only exhibited publicly for the first time in 1865 for the 600th anniversary of Dante’s birth and of Italian unification. Now, they are on display, virtually, for free, as part of a “year-long calendar of events to mark the 700th anniversary of the poet’s death.” This is an extraordinary opportunity to see these illustrations, which have until now “only been seen by a few scholars and displayed to the public only twice, and only in part,” says Uffizi director Eike Schmidt.

Much of the promised “didactic-scientific comment” to accompany each drawing is marked as “upcoming” on the English version of the Uffizi site, but you can see high resolution scans of each drawing and zoom in to examine the many tortures of the damned and the grotesque demons who torment them. Learn much more at Khan Academy about how Dante’s literary epic in terza rima left “a lasting impression on the Western imagination for more than half a millennium,” solidifying and reshaping images of hell “into new guises that would become familiar to countless generations that followed.” If you like, you can also take a free course on Dante’s Divine Comedy from Yale University.

via MyModernMet/The Guardian

Related Content:

Why Should We Read Dante’s Divine Comedy? An Animated Video Makes the Case

A Digital Archive of the Earliest Illustrated Editions of Dante’s Divine Comedy (1487–1568)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...A 3,000-Year-Old Painter’s Palette from Ancient Egypt, with Traces of the Original Colors Still In It

It’s a good bet your first box of crayons or watercolors was a simple affair of six or so colors… just like the palette belonging to Amenemopet, vizier to Pharaoh Amenhotep III (c.1391 — c.1354 BC), a pleasure-loving patron of the arts whose rule coincided with a period of great prosperity.

Amenemopet’s well-used artist’s palette, above, now resides in the Egyptian wing of New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Over 3000 years old and carved from a single piece of ivory, the palette is marked “beloved of Re,” a royal reference to the sun god dear to both Amenhotep III and Akhenaton, his son and successor, whose worship of Re resembled monotheism.

As curator Catharine H. Roehrig notes in the Metropolitan’s publication, Life along the Nile: Three Egyptians of Ancient Thebes, the palette “contains the six basic colors of the Egyptian palette, plus two extras: reddish brown, a mixture of red ocher and carbon; and orange, a mixture of orpiment (yellow) and red ocher. The painter could also vary his colors by applying a thicker or thinner layer of paint or by adding white or black to achieve a lighter or darker shade.”

(Careful when mixing that orpiment into your red ocher, kids. It’s a form of arsenic.)

Other minerals that would have been ground and combined with a natural binding agent include gypsum, carbon, iron oxides, blue and green azurite and malachite.

The colors themselves would have had strong symbolism for Amenhotep and his people, and the artist would have made very deliberate—regulated, even—choices as to which pigment to load onto his palm fiber brush when decorating tombs, temples, public buildings, and pottery.

As Jenny Hill writes in Ancient Egypt Online, iwn—color—can also be translated as “disposition,” “character,” “complexion” or “nature.” She delves into the specifics of each of the six basic colors:

Wadj (green) also means “to flourish” or “to be healthy.” The hieroglyph represented the papyrus plant as well as the green stone malachite (wadj). The color green represented vegetation, new life and fertility. In an interesting parallel with modern terminology, actions which preserved the fertility of the land or promoted life were described as “green.”

Dshr (red) was a powerful color because of its association with blood, in particular the protective power of the blood of Isis…red could also represent anger, chaos and fire and was closely associated with Set, the unpredictable god of storms. Set had red hair, and people with red hair were thought to be connected to him. As a result, the Egyptians described a person in a fit of rage as having a “red heart” or as being “red upon” the thing that made them angry. A person was described as having “red eyes” if they were angry or violent. “To redden” was to die and “making red” was a euphemism for killing.

Irtyu (blue) was the color of the heavens and hence represented the universe. Many temples, sarcophagi and burial vaults have a deep blue roof speckled with tiny yellow stars. Blue is also the color of the Nile and the primeval waters of chaos (known as Nun).

Khenet (yellow) represented that which was eternal and indestructible, and was closely associated with gold (nebu or nebw) and the sun. Gold was thought to be the substance which formed the skin of the gods.

Hdj (white) represented purity and omnipotence. Many sacred animals (hippo, oxen and cows) were white. White clothing was worn during religious rituals and to “wear white sandals” was to be a priest…White was also seen as the opposite of red, because of the latter’s association with rage and chaos, and so the two were often paired to represent completeness.

Kem (black) represented death and the afterlife to the ancient Egyptians. Osiris was given the epithet “the black one” because he was the king of the netherworld, and both he and Anubis (the god of embalming) were portrayed with black faces. The Egyptians also associated black with fertility and resurrection because much of their agriculture was dependent on the rich dark silt deposited on the river banks by the Nile during the inundation. When used to represent resurrection, black and green were interchangeable.

via My Modern Met

Related Content:

Wonders of Ancient Egypt: A Free Online Course from the University of Pennsylvania

Pyramids of Giza: Ancient Egyptian Art and Archaeology–a Free Online Course from Harvard

Take a 3D Tour Through Ancient Giza, Including the Great Pyramids, the Sphinx & More

What Ancient Egyptian Sounded Like & How We Know It

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. She most recently appeared as a French Canadian bear who travels to New York City in search of food and meaning in Greg Kotis’ short film, L’Ourse. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...David Chase Talks Sopranos for 90 Minutes on the Talking Sopranos Podcast

During the early days of the pandemic, the Talking Sopranos podcast (previously discussed on OC here) got underway. Hosted by Michael Imperioli (Christopher Moltisanti) and Steve Schirripa (Bobby Bacala), the podcast revisits every episode of HBO’s groundbreaking TV series. It starts naturally with the 1999 pilot and then moves forward sequentially. And each installment features a guest (usually an actor, writer, or director who contributed to the show), followed by a scene-by-scene breakdown of a complete Sopranos episode. (They covered the celebrated “Pine Barrens” episode a few weeks back.) Past guests have included Edie Falco, Aida Turturro, Steve Buscemi, Lorraine Bracco and more.

Now almost halfway through the entire series, Imperioli and Schirripa spent 90 minutes this week with Sopranos’ creator David Chase. In a rare interview (watch above), Chase talks about his creative ambitions for the show, the real people (friends and acquaintances) he modeled characters on, his sometimes friction-filled relationship with James Gandolfini, and the upcoming Sopranos film.

You can listen to Talking Sopranos on Apple, Spotify and Google, or watch all episodes on YouTube. And if you’d like to supplement all of this with more detail, get a copy of Matt Zoller Seitz and Alan Sepinwall’s book The Sopranos Sessions. It’s highly recommended.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content

How David Chase Breathed Life into the The Sopranos

David Chase Reveals the Philosophical Meaning of The Sopranos’ Final Scene

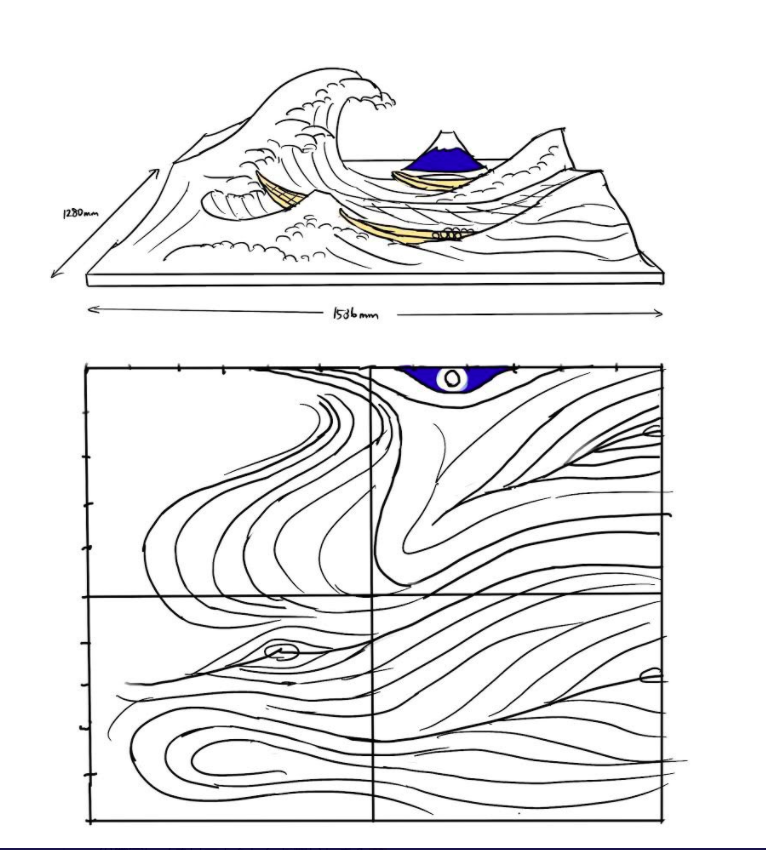

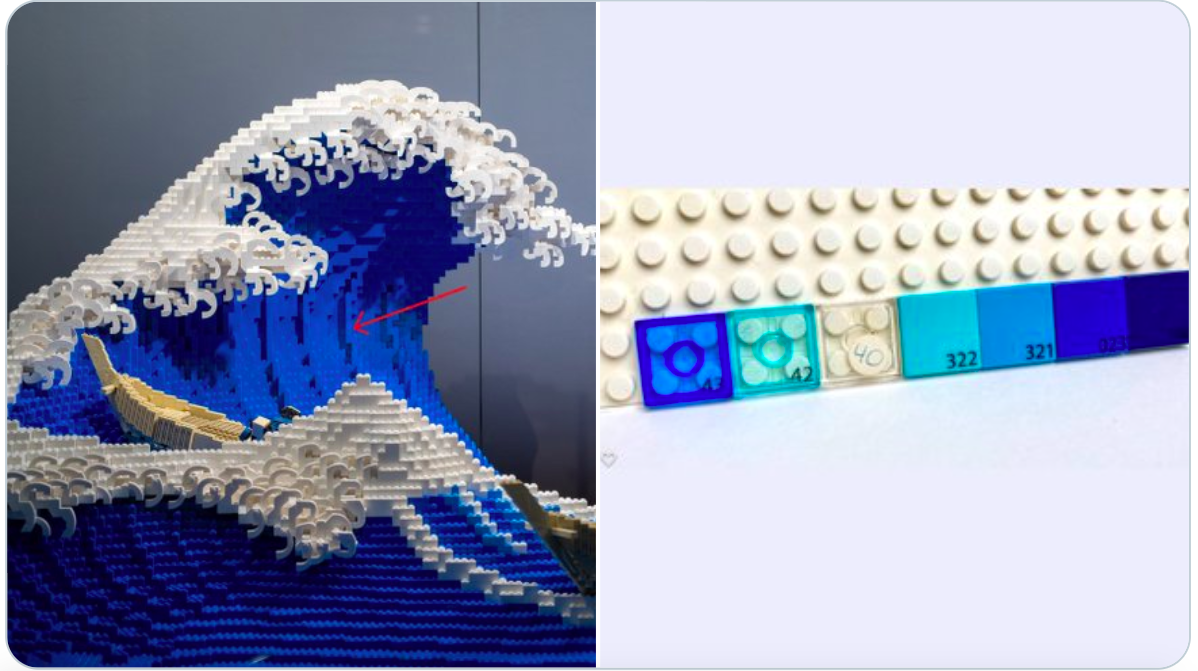

Read More...Hokusai’s Iconic Print, “The Great Wave off Kanagawa,” Recreated with 50,000 LEGO Bricks

For those with the time, skill, and drive, LEGO is the perfect medium for wildly impressive recreations of iconic structures, like the Taj Mahal, Eiffel Tower, the Titanic and now the Roman Colosseum.

But water? A wave?

And not just any wave, but Katsushika Hokusai’s celebrated 19th-century woodblock print, The Great Wave off Kanagawa.

As Open Culture’s Colin Marshall pointed out earlier, you might not know the title, but the image is instantly recognizable.

Artist Jumpei Mitsui, the world’s youngest LEGO Certified Professional, was undeterred by the thought of tackling such a dynamic and well known subject.

While other LEGO enthusiasts have created excellent facsimiles of famous artworks, doing justice to the curves and implied motion of The Great Wave seems a nearly impossible feat.

Having spent his childhood in a house by the sea, waves are a familiar presence to Mitsui. To get a better sense of how they work, he read several scientific papers and spent four hours studying wave videos on YouTube.

He made only one preparatory sketch before beginning the build, an effort that required 50,000 some LEGO pieces.

His biggest hurdle was choosing which color bricks to use in the area indicated by the red arrow in the photo below. Hokusai had taken advantage of the newly affordable Berlin blue pigment in the original.

Mitsui tweeted:

I tried a total of 7 colors including transparent parts, but in the end, I adopted the same blue color as the waves. If you use other colors, the lines will be overemphasized and unnatural, but if you use blue, the shade will be created just by adjusting the light, and the natural lines will appear nicely. It can be said that it was possible because it was made three-dimensional.

Jumpei Mitsui’s wave is now on permanent view at Osaka’s Hankyu Brick Museum.

via Spoon and Tamago and Colossal

Related Content:

The Frank Lloyd Wright Lego Set

With 9,036 Pieces, the Roman Colosseum Is the Largest Lego Set Ever

Why Did LEGO Become a Media Empire? Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #37

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. She most recently appeared as a French Canadian bear who travels to New York City in search of food and meaning in Greg Kotis’ short film, L’Ourse. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

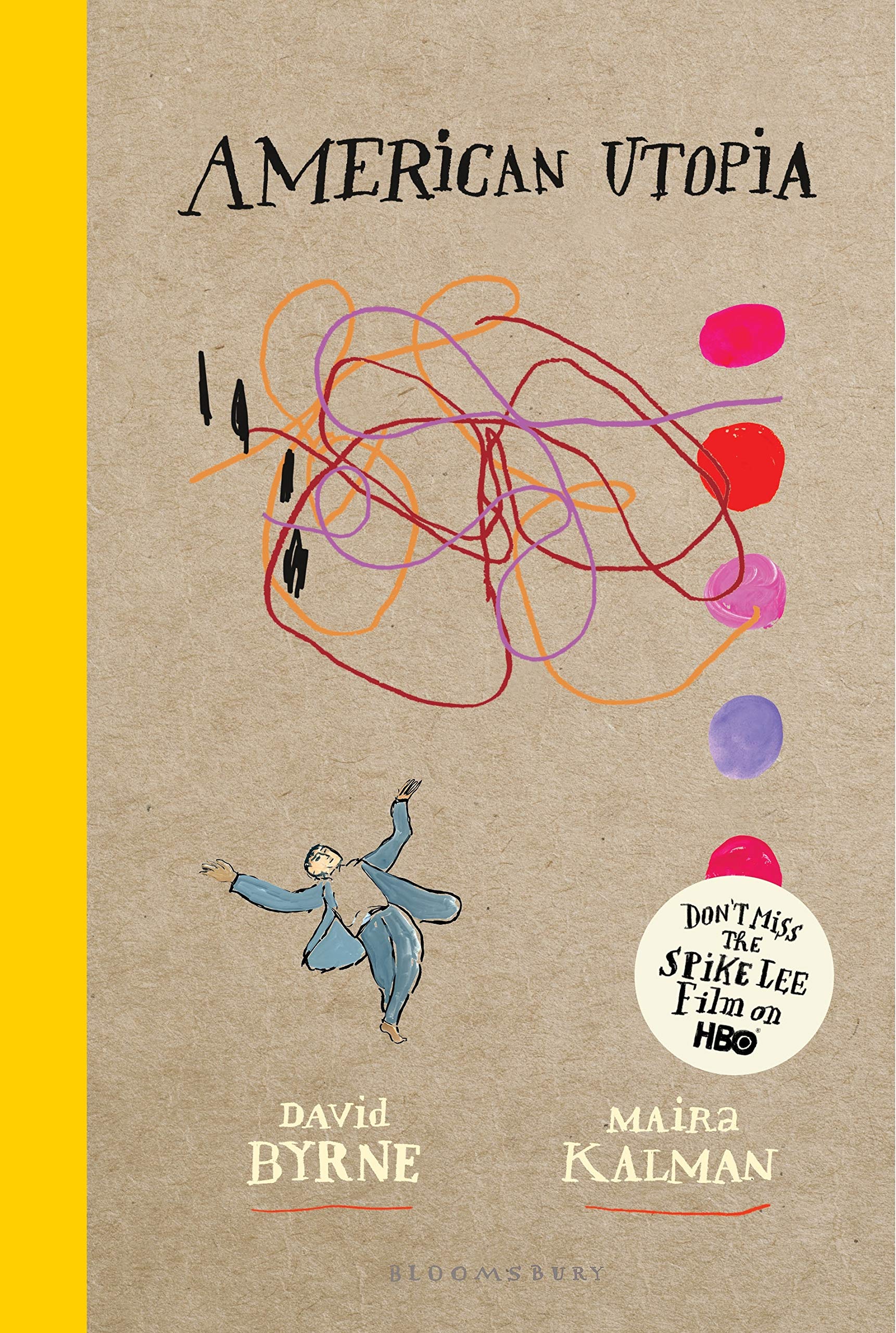

Read More...David Byrne Turns His Acclaimed Musical American Utopia into a Picture Book for Grown-Ups, with Vivid Illustrations by Maira Kalman

Whatever your feelings about the sentimental, lighthearted 1960 Disney film Pollyanna, or the 1913 novel on which it’s based, it’s fair to say that history has pronounced its own judgment, turning the name Pollyanna into a slur against excessive optimism, an epithet reserved for adults who display the guileless, out-of-touch naïveté of children. Pitted against Pollyanna’s effervescence is Aunt Polly, too caught up in her grown-up concerns to recognize, until it’s almost too late, that maybe it’s okay to be happy.

Maybe we all have to be a little like practical Aunt Polly, but do we also have a place for Pollyannas? Can that not also be the role of the modern artist? David Byrne hasn’t been waiting for permission to spread joy in his late career. Contra the common wisdom of most adults, a couple years back Byrne began to gather positive news stories under the heading Reasons to Be Cheerful, now an online magazine.

Then, Byrne had the audacity to call a 2018 album, tour, and Broadway show American Utopia, and the gall to have Spike Lee direct a concert film with the same title, and release it smack in the middle of 2020, a year all of us will be glad to see in hindsight. Byrne’s two-year endeavor can be seen as his answer to “American Carnage,” the grim phrase that began the Trump era.

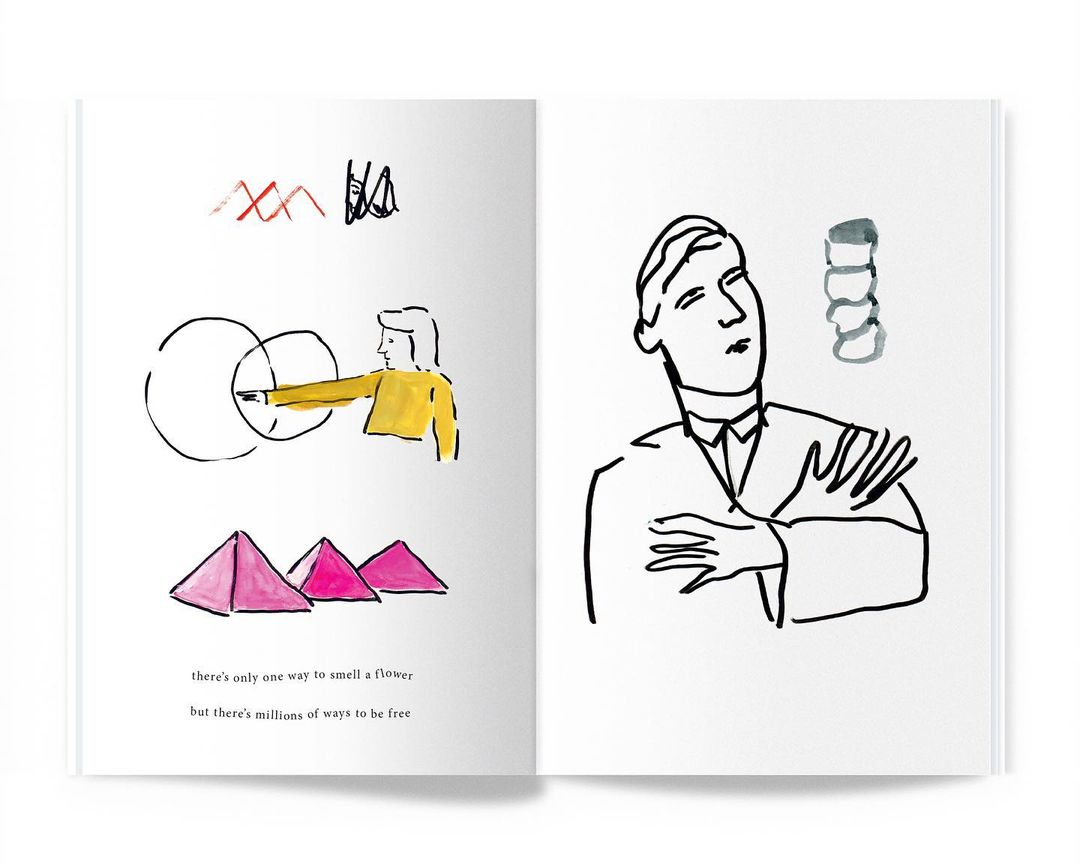

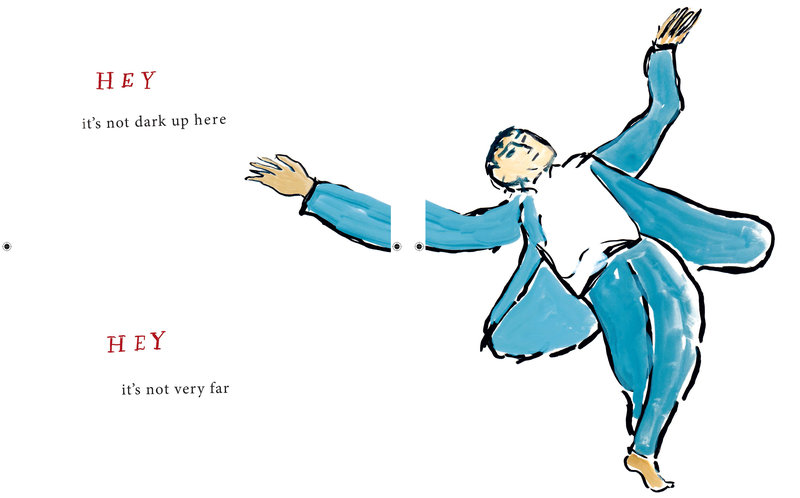

As if all that weren’t enough, American Utopia is now an “impressionistic, sweetly illustrated adult picture book,” as Lily Meyer writes at NPR, “a soothing and uplifting, if somewhat nebulous, experience of art.” Working with artist Maira Kalman, Byrne has turned his conceptual musical into something like a “book-length poem… filled with charming illustrations of trees, dancers, and party-hatted dogs.”

Byrne’s project is not naive, Maria Popova argues at Brain Pickings, it’s Whitmanesque, a salvo of irrepressible optimism against “a kind of pessimistic ahistorical amnesia” in which we “judge the deficiencies of the present without the long victory ledger of past and fall into despair.” American Utopia doesn’t articulate this so much as perform it, either with bare feet and gray suits onstage or the vivid colors of Kalman’s drawings, “lightly at odds,” Meyer notes, “with Byrne’s words, transforming their plain optimism into a more nuanced appeal.”

American Utopia the book, like the musical before it, was written and drawn before the pandemic. Do Byrne and Kalman still have reasons to be cheerful post-COVID? Just last week, they sat down with Isaac Fitzgerald for Live Talks LA to discuss it. You can see the whole, hour-long conversation just above. Kalman confesses she’s still in “quiet shock,” but finds hope in historical perspective and “incredible people out there doing fantastic things.”

Byrne takes us on one of his fascinating investigations into the history of thought, referencing a theorist named Aby Warburg who saw in the sum total of art a kind “animated life” that connects us, past, present, and future, and who reminded him, “Yes, there are other ways of thinking about things!” Perhaps the visionary and the Pollyannaish need not be so far apart. See several more of Kalman and Byrne’s beautifully optimistic pages from American Utopia, the book, at Brain Pickings.

Related Content:

David Byrne’s American Utopia: A Sneak Preview of Spike Lee’s New Concert Film

Watch Life-Affirming Performances from David Byrne’s New Broadway Musical American Utopia

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...