Image by Zairon, via Wikimedia Commons

Among the non-wine-related points of interest in the Loire Valley, the Château de Chambord stands tall — or rather, both tall and wide, being easily the largest château in the region. “A Unesco World Heritage site with more than 400 rooms, including reception halls, kitchens, lapidary rooms and royal apartments,” writes Adrienne Bernhard at BBC Travel, it “boasts a fireplace for every day of the year.” No less vast and elaborate a hunting lodge would do for King Francis I, who had it built between 1519 and 1547, though the identity of the architect from whom he commissioned the plans has been lost to history. But the unusual design of its central staircase — and central tourist attraction — suggests an intriguing name indeed: Leonardo da Vinci.

“In 1516, Leonardo left his studio in Rome to join the court of King Francis I as ‘premier peintre et ingénieur et architecte du Roi,’ ” Bernhard writes. “Francis I enthusiastically embraced the cultural Renaissance that had swept Italy, eager to put his imprimatur on the arts, and in 1516 commissioned plans for his dream castle at the site of Romorantin. For Leonardo, it was an ideal assignment – the culmination of an illustrious career, allowing the artist to express many of his passions: architecture, urban planning, hydraulics and engineering.” But not long after its construction began, the Romorantin project was abandoned, and by the time Francis got started on what would become Château de Chambord, Leonardo was already dead.

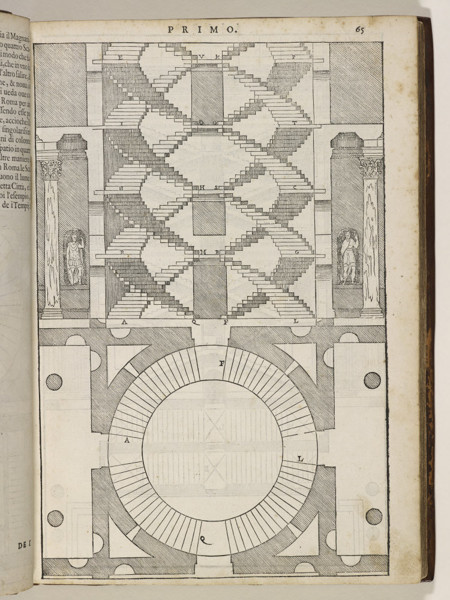

Leonardo’s influence nevertheless seems present in the finished castle: in its Greek cross-shaped floor plan, in its large copula, and most of all in its “double helix” staircase, which resembles certain designs contained in his Codex Atlanticus. “The celebrated staircase consists in a hollowed central core and, twisting and turning one above the other, twinned helical ramps servicing the main floors of the building,” says the Château de Chambord’s official site. “Magically enough, when two persons use the different sets of staircases at the same time, they can see each other going up or down, yet never meet.” (Blogger Gretchen M. Greer writes that “one woman I traveled with found the staircase so strikingly symbolic of the marital disharmony and disconnect that resulted in her divorce that she declared the beautiful architectural feature the ugliest place in the Loire.”)

Some scholars, like Hidemichi Tanaka, identify the hand of Leonardo in practically every detail of the château. “Seen from afar, the roof terrace, with its multitude of architectural embellishments, is suggestive of a soaring city skyline,” he writes in a 1992 article in the journal Artibus et Historiae. “It may be worth comparing the ‘city in stone’ with the townscape in the background of Leonardo’s Annunciation in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence, as well as with the structures in the drawings of floods which the artist made in his later years.” Though perhaps a chronologically implausible achievement, the design of the Château de Chambord would have been neither technically nor aesthetically beyond him. And indeed, who wouldn’t be pleased to see medieval castle architecture paid such extravagant and still-impressive tribute by the quintessential Renaissance man?

Related content:

Leonardo da Vinci Designs the Ideal City: See 3D Models of His Radical Design

Explore the Largest Online Archive Exploring the Genius of Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci’s Elegant Design for a Perpetual Motion Machine

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.