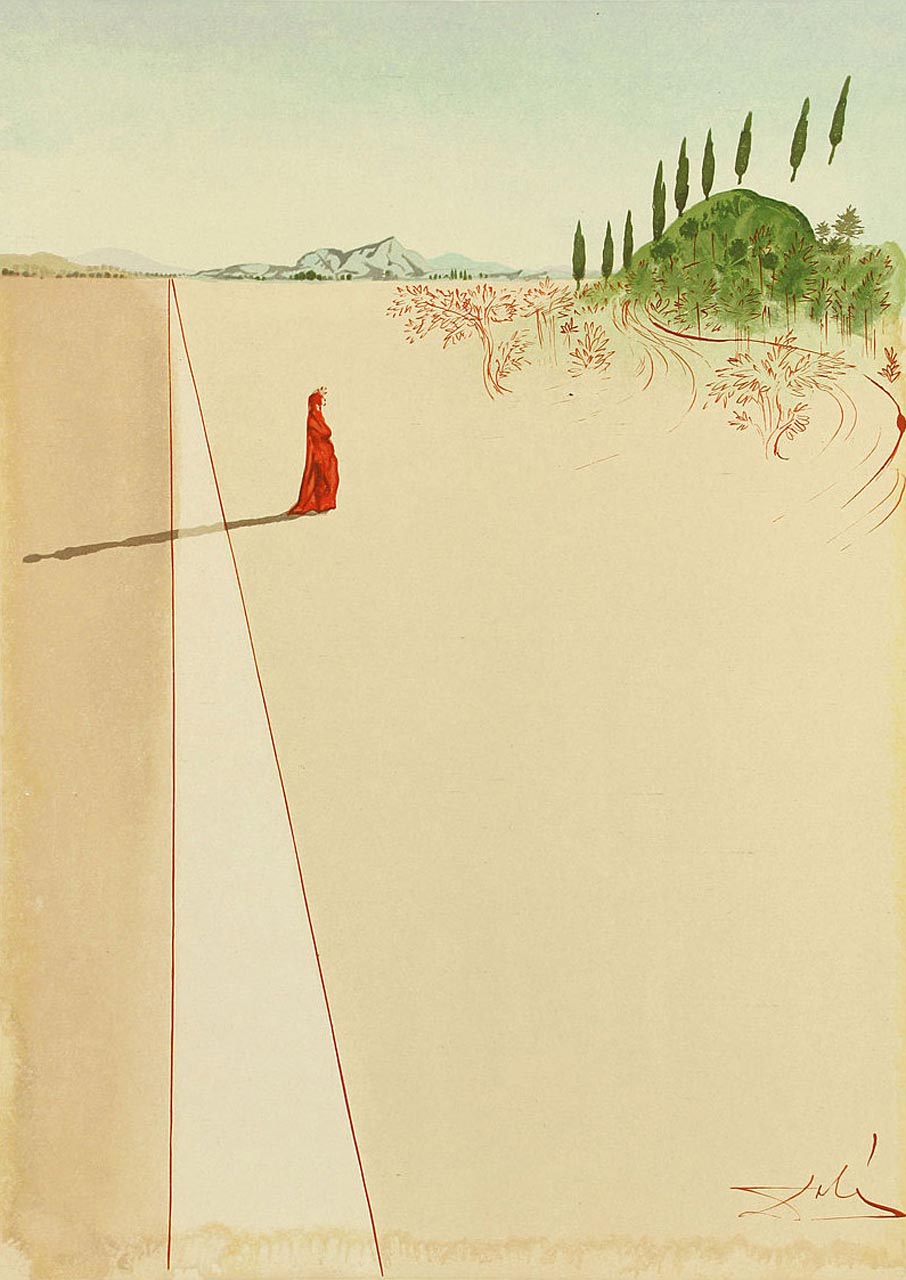

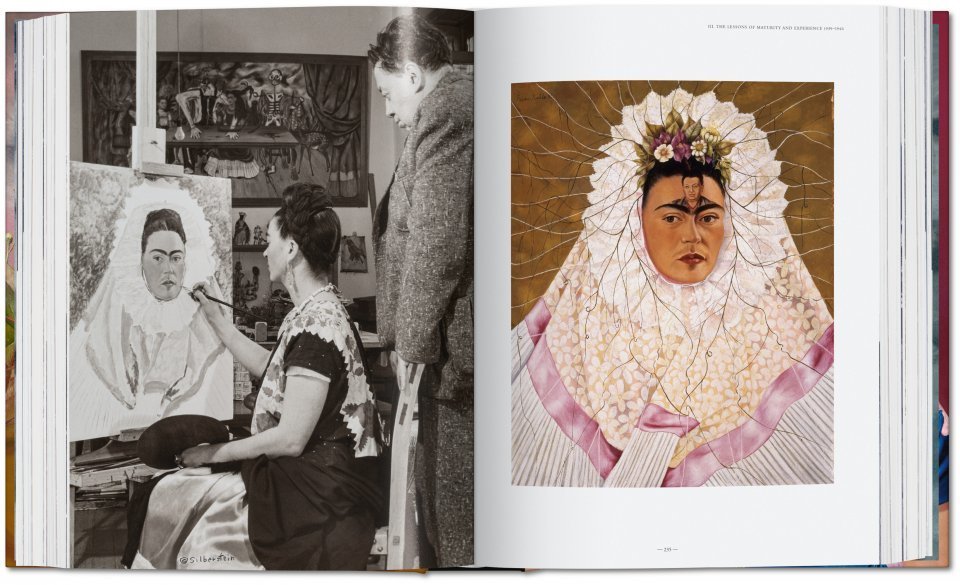

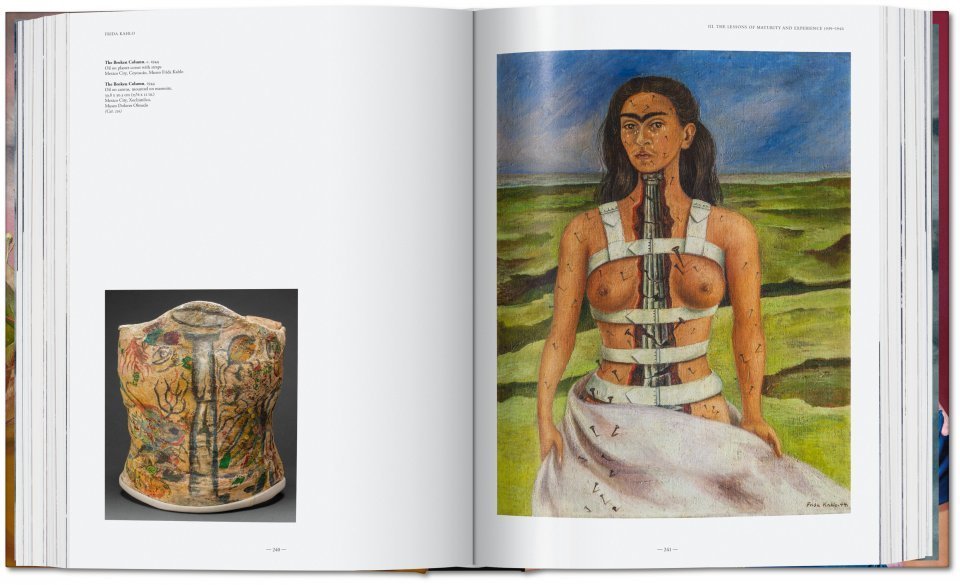

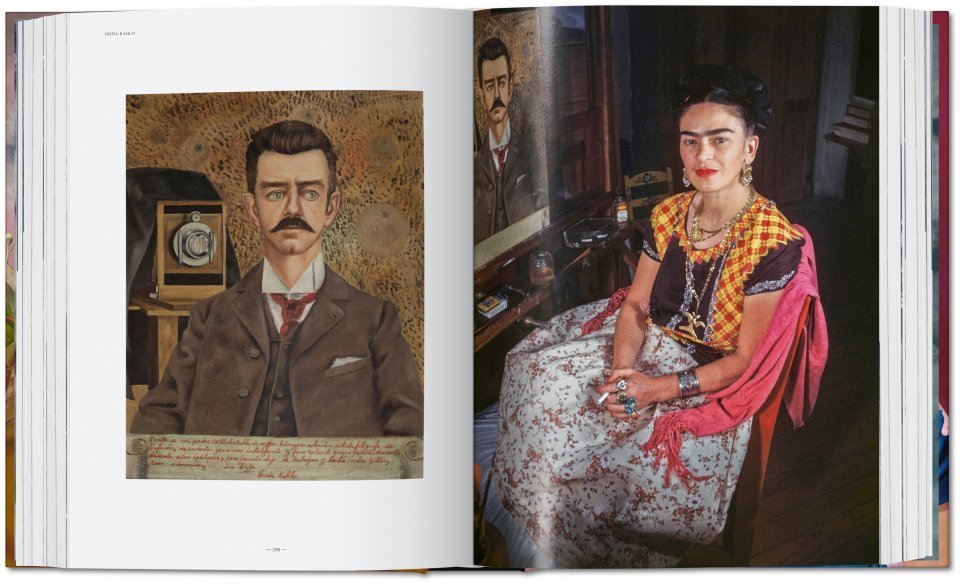

Most of us who know Frida Kahlo’s work know her self-portraits. But, in her brief 47 years, she created a more various body of work: portraits of others, still lifes, and difficult-to-categorize visions that still, 67 years after her death, feel drawn straight from the wild currents of her imagination. (Not to mention her elaborately illustrated diary, previously featured here on Open Culture.) Somehow, Kahlo’s work has never all been gathered in one place. That, along with her enduring appeal as both an artist and a historical figure, surely made her an appealing proposition for art-book publisher Taschen, an operation as invested in visual richness as it is in completeness.

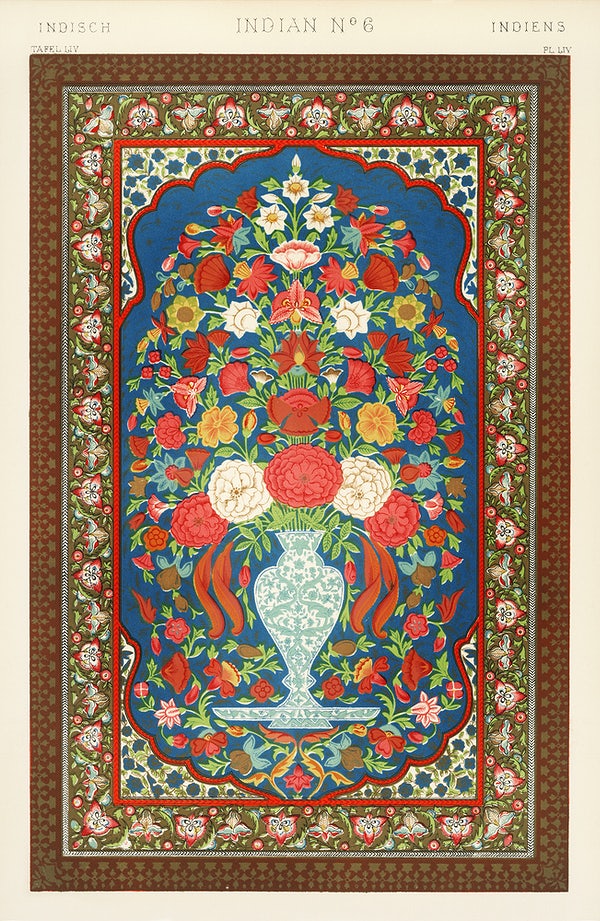

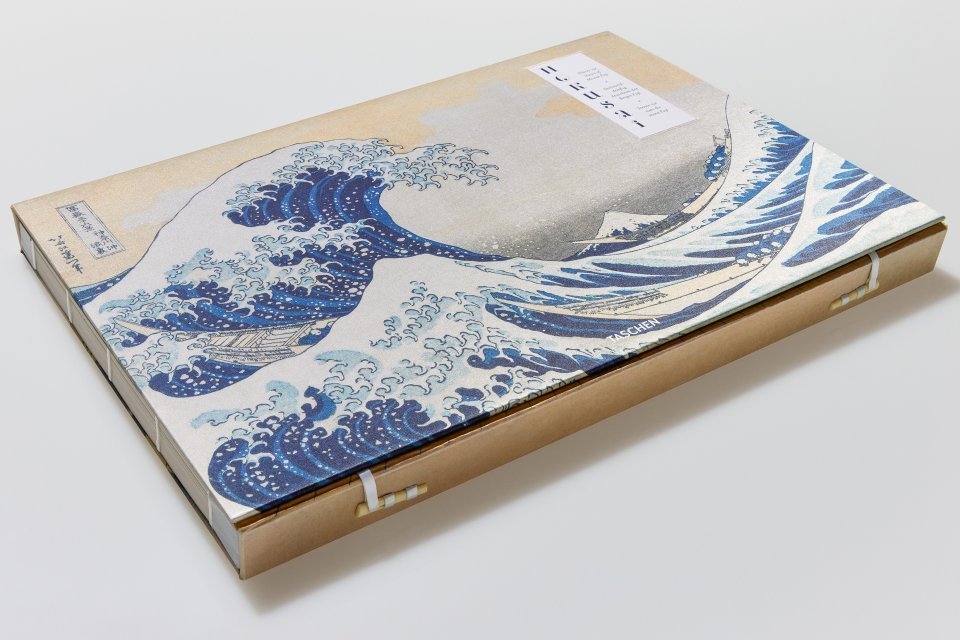

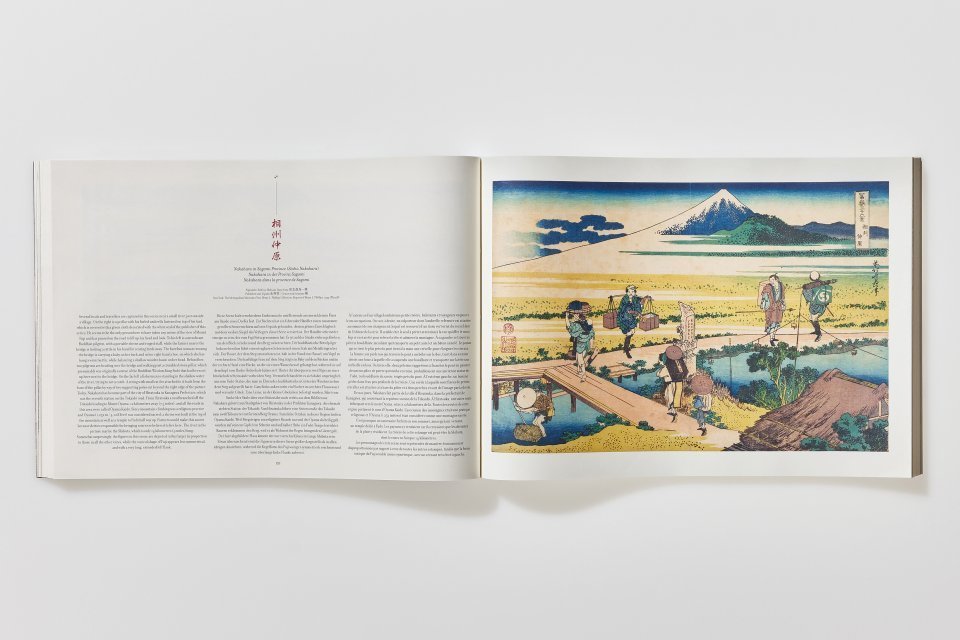

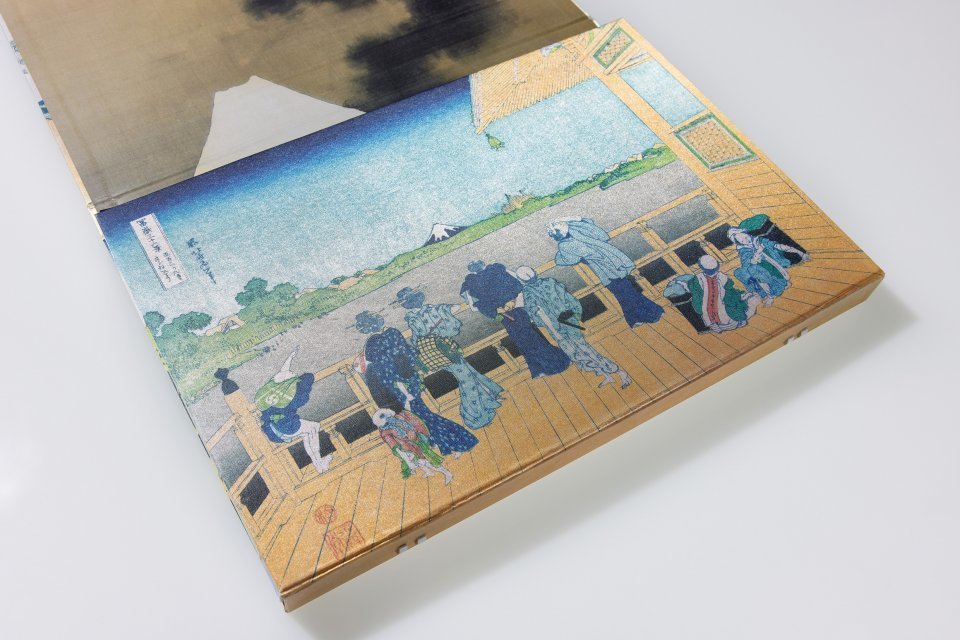

There’s also the matter of size. Though not conceived at the same scale as the murals of Diego Rivera, with whom Kahlo lived in not one but two less-than-conventional marriages, Kahlo’s paintings look best when seen at their biggest. Hence Taschen’s “large-format XXL” production of Frida Kahlo: The Complete Paintings, which “allows readers to admire Frida Kahlo’s paintings like never before, including unprecedented detail shots and famous photographs.” Presented along with a biographical essay, those photos capture, among other subjects, “Frida, Diego, and the Casa Azul, Frida’s home and the center of her universe.”

In creating his volume, editor-author Luis-Martín Lozano and contributors Andrea Kettenmann and Marina Vázquez Ramos focused not on the artist’s life, but her work. “Most people at exhibitions, they’re interested in her personality — who she is, how she dressed, who does she go to bed with, her lovers, her story,” says Lozano in an interview with BBC Culture. Putting together a run-of-the-mill Kahlo book, “you repeat the same things, and it will sell – because everything about Kahlo sells. It’s unfortunate to say, but she’s become a merchandise.” Frida Kahlo: The Complete Paintings is also, of course, a product, and one painstakingly designed to compel the Frida Kahlo enthusiast. Its ideal reader, however, desires to live in not Kahlo’s world, but the world she created.

via Colossal

Related Content:

Frida Kahlo: The Life of an Artist

The Intimacy of Frida Kahlo’s Self-Portraits: A Video Essay

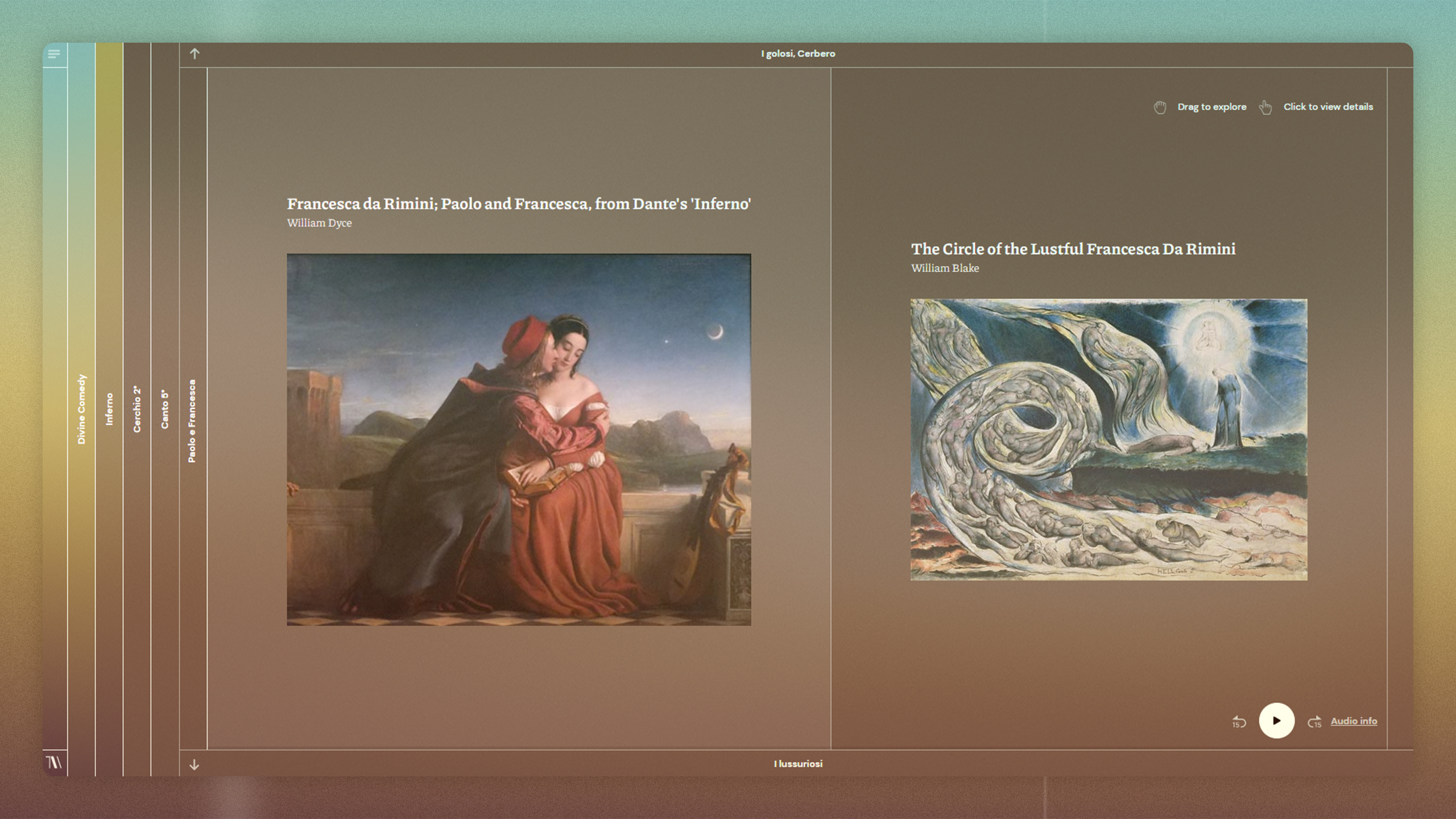

Take a Virtual Tour of Frida Kahlo’s Blue House Free Online

A Brief Animated Introduction to the Life and Work of Frida Kahlo

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.