Creative Commons image via Wikimedia Commons

Artist and music producer Brian Eno wrote one of my very favorite books: A Year with Swollen Appendices, which takes the form of his personal diary of the year 1995 with essayistic chapters (the “swollen appendices”) on topics like “edge culture,” generative music, new ways of , pretension, CD-ROMs (a relevant topic back then), and payment structures for recording artists (a relevant topic again today). It also includes a fair bit of Eno’s correspondence with Stewart Brand, once editor of the Whole Earth Catalog and now president of the Long Now Foundation, “a counterpoint to today’s accelerating culture” meant to “help make long-term thinking more common” and “creatively foster responsibility in the framework of the next 10,000 years.”

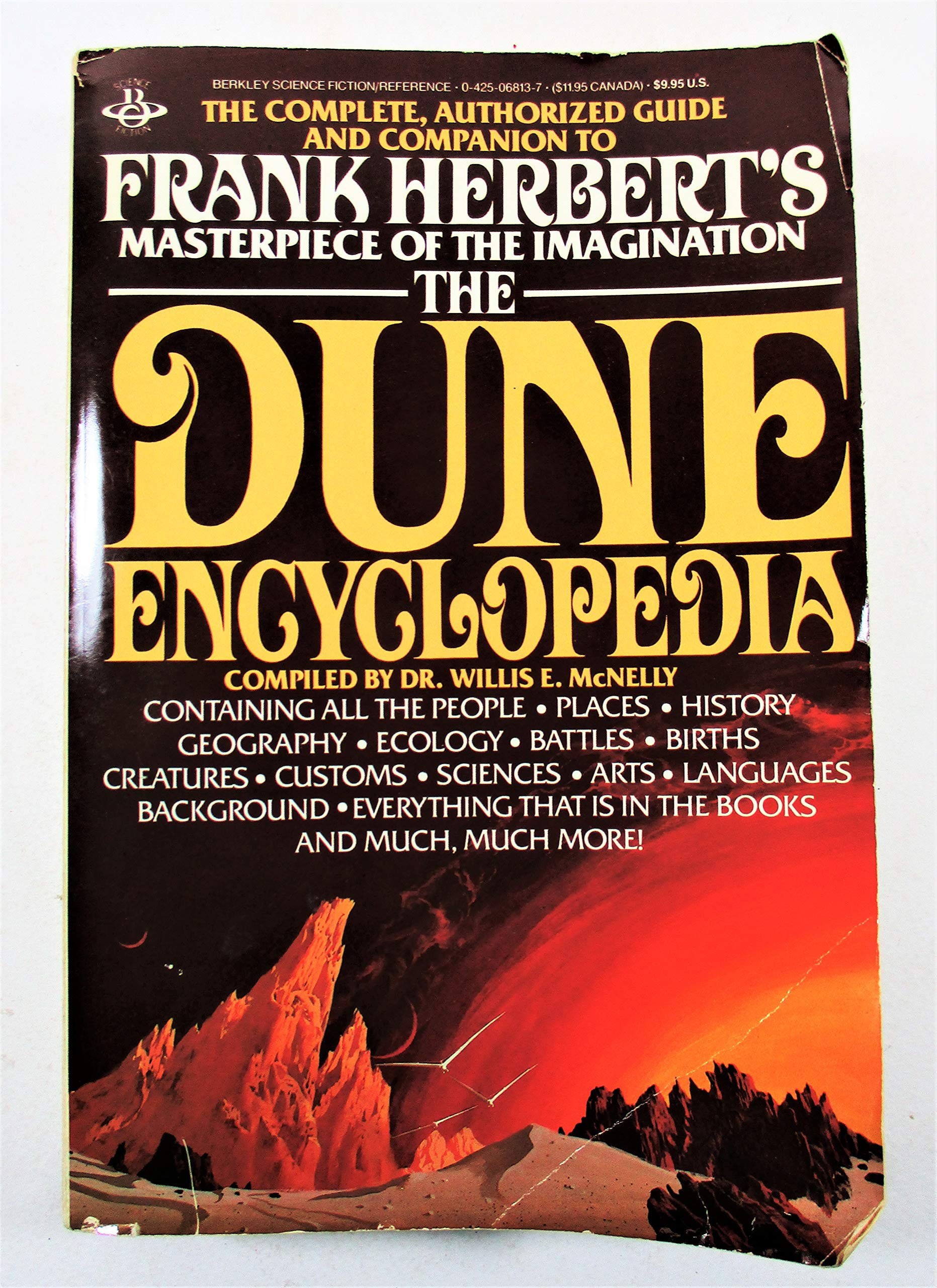

It so happens that Eno now sits on the Long Now Foundation’s board and has had a hand in some of its projects. Naturally, he contributed suggested reading material to the foundation’s Manual of Civilization, a collection of books humanity could use to rebuild civilization, should it need rebuilding. Eno’s full list, which spans history, politics, philosophy, sociology, architecture, design, nature, and literature, runs as follows:

- Seeing Like a State by James C Scott

- The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art by David Lewis-Williams

- Crowds and Power by Elias Canetti

- The Wheels of Commerce by Fernand Braudel

- Keeping Together in Time by William McNeill

- Dancing in the Streets by Barbara Ehrenreich

- Roll Jordan Roll by Eugene Genovese

- A Pattern Language by Christopher Alexander et al

- The Face of Battle by John Keegan

- A History of the World in 100 Objects by Neil MacGregor

- Contingency, Irony and Solidarity by Richard Rorty

- The Notebooks by Leonardo da Vinci

- The Confidence Trap by David Runciman

- The Discoverers by Daniel Boorstein

- Mother Nature: A History of Mothers, Infants, and Natural Selection by Sarah Hrdy

- War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy

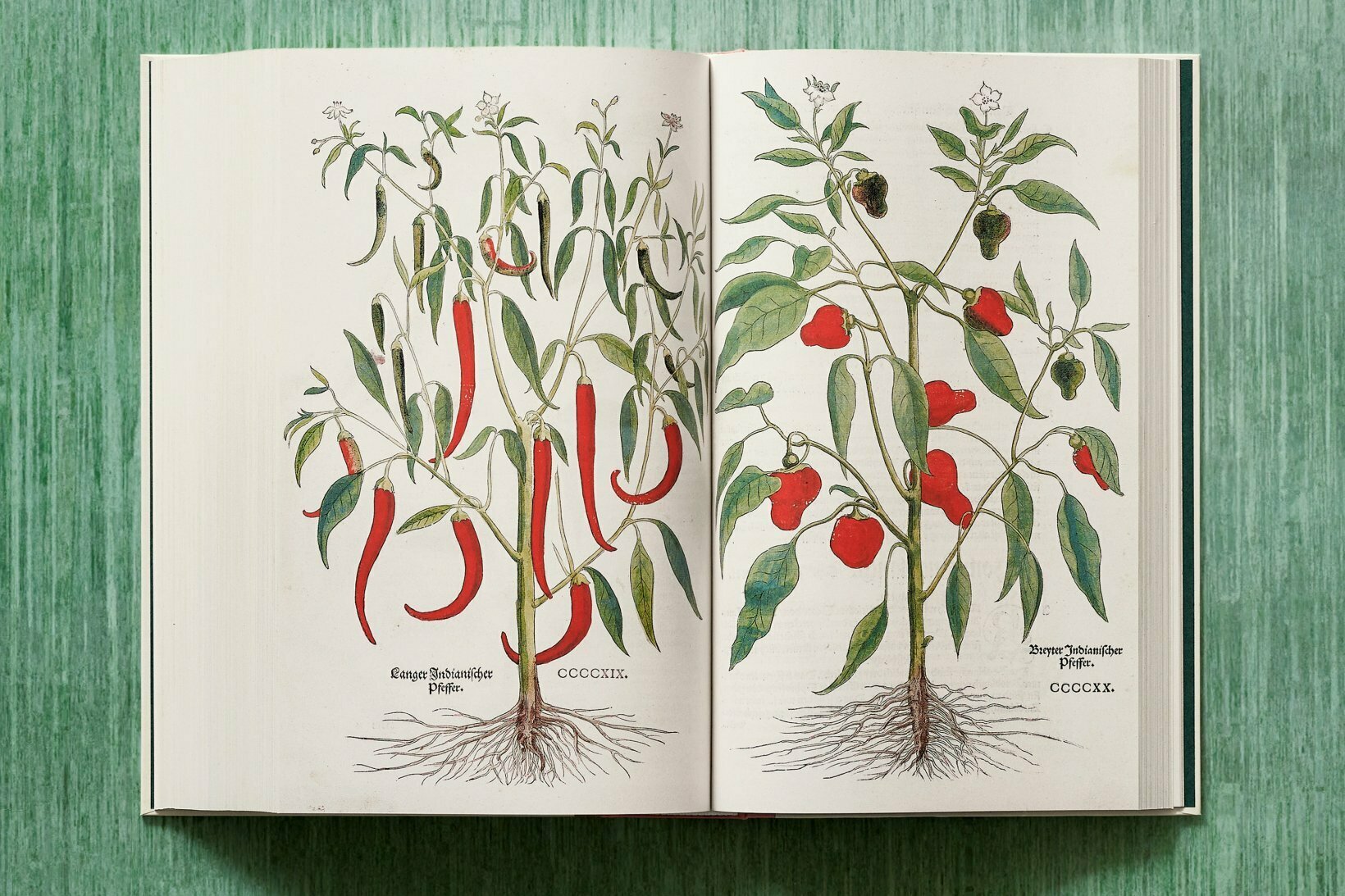

- The Cambridge World History of Food (2‑Volume Set) by Kenneth F. Kiple & Kriemhild Coneè Ornelas

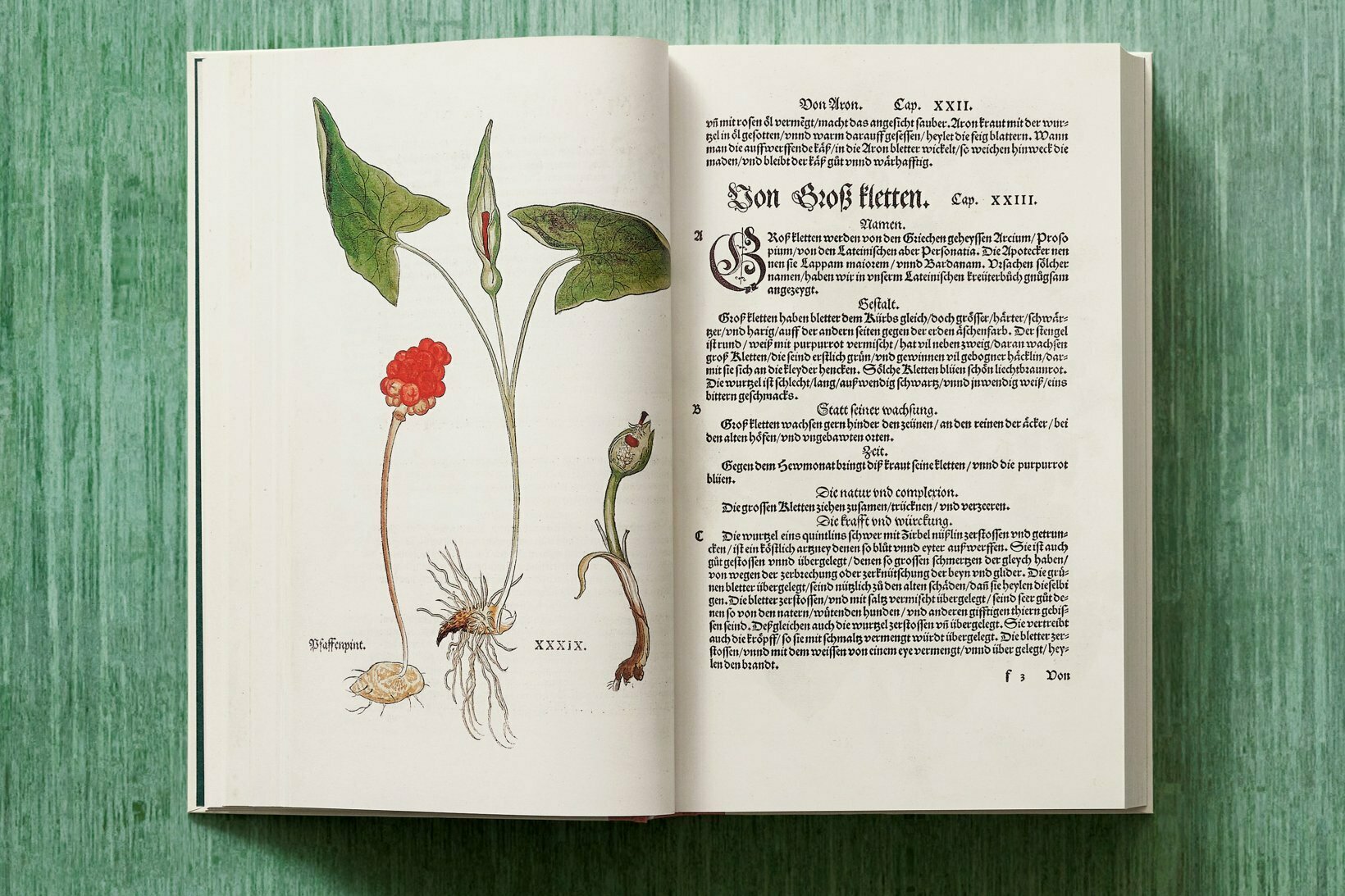

- The Illustrated Flora of Britain and Northern Europe by Marjorie Blamey & Christopher Grey Wilson

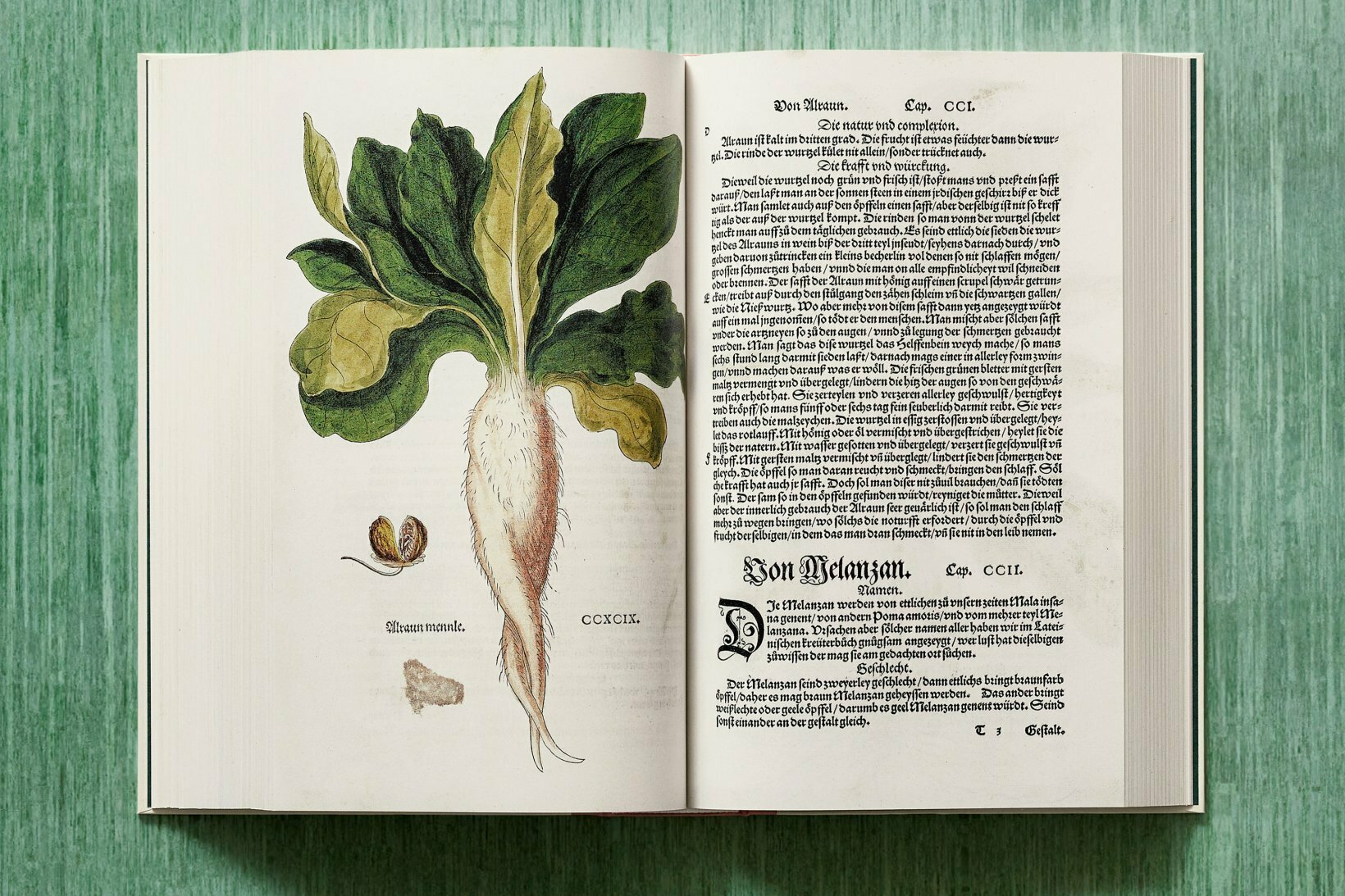

- Printing and the Mind of Man by John Carter & Percy Muir

- Peter the Great: His Life and World by Richard Massie

If you’d like to know more books that have shaped Eno’s thinking, do pick up a copy of A Year with Swollen Appendices. Like all the best diarists, Eno makes plenty of references to his day-to-day reading material, and at the very end — beyond the last swollen appendix — he includes a bibliography (below), on which you’ll find more from Christopher Alexander, a reappearance of Rorty’s Contingency, Irony and Solidarity, and even Steward Brand’s own How Buildings Learn (on a television version of which the two would collaborate). You can find other writers and thinkers’s contributions to the Manual of Civilization here.

- Best Ideas: A Compendium of Social Innovation edited by Nicholas Albery

- A Foreshadowing of the 21st Century Art: The Color and Geometry of Very Early Turkish Carpets by Christopher Alexander

- Bridge Over the Drina by Ivo Andric

- Jihad vs. McWorld by Benjamin Barber

- The Artful Universe by John Barrow

- Brain of the Firm by Stafford Beer

- Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil by John Berendt

- The Creators by Daniel Boorstin

- Lay My Burden Down: A Folk History of Slavery edited by B.A. Botkin

- How Buildings Learn by Stewart Brand

- Civilization and Capitalism by Fernand Braudel

- The Transformation of War by Martin van Creveld

- The Transfiguration of the Commonplace by Arthur Danto

- River Out of Eden by Richard Dawkins

- Darwin’s Dangerous Idea by Daniel Dennett

- Defence Policy Making edited by G.M. Dillon

- Women En Large: Image of Fat Nudes by Laurie Toby Edison and Debbie Notkin

- Birdsong by Sebastian Faulks

- Trust by Francis Fukuyama

- Edge City by Joel Garreau

- Ecce Homo by George Grosz

- Beyond Culture by Edward T. Hall

- Managing the Commons by Garrett Hardin and John Baden

- The Middle Ages by Friedrich Herr

- Going Bugs by James Hillman

- Culture of Complaint by Robert Hughes

- The Waning of the Middle Ages by Johann Huizinga

- The State We’re In by Will Hutton

- Out of Control: The Rise of Neo-Biological Civilization by Kevin Kelly

- Wild Blue Yonder by Nick Krotz

- Fetish Girls by Eric Kroll

- The Leopard by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa

- Artificial Life by Steven Levy

- Planetary Overload by A.J. McMichael

- Being Digital by Nicholas Negroponte

- Erotica Universalis by Gilles Neret

- Living Without a Goal by Jay Ogilvy

- Billy the Kid by Michael Ondaatje

- Evolution of Consciousness by Robert E. Ornstein

- Art and Pornography and Man’s Rage for Chaos by Morse Peckham

- Works and Texts by Tom Phillips

- The Language Instinct by Stephen Pinker

- In Search of a Better World by Karl Popper

- Prisoner’s Dilemma by William Poundstone

- Postcards by Annie Proulx

- Consequences of Pragmatism and Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity by Richard Rorty

- The Moor’s Last Sigh by Salman Rushdie

- England’s Dreaming by Jon Savage

- Lords of the Rim by Sterling Seagrave

- Art and Physics by Leonard Shlain

- I am That: Conversations with Sri Nisaragadatta Maharaj

- Face of the Gods and Flash of the Spirit by Robert Farris Thompson

- Ocean of Sound by David Toop

- The Seven Cultures of Capitalism by Charles Hampden Turner

- Black Lamb and Grey Falcon by Rebecca West

- Art and Anarchy by Edgar Wind

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2015.

Related Content:

Jump Start Your Creative Process with Brian Eno’s “Oblique Strategies”

Brian Eno on Creating Music and Art As Imaginary Landscapes (1989)

What Books Should Every Intelligent Person Read?: Tell Us Your Picks; We’ll Tell You Ours

Neil deGrasse Tyson Lists 8 (Free) Books Every Intelligent Person Should Read

The 10 Greatest Books Ever, According to 125 Top Authors (Download Them for Free)

Colin Marshall writes on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.