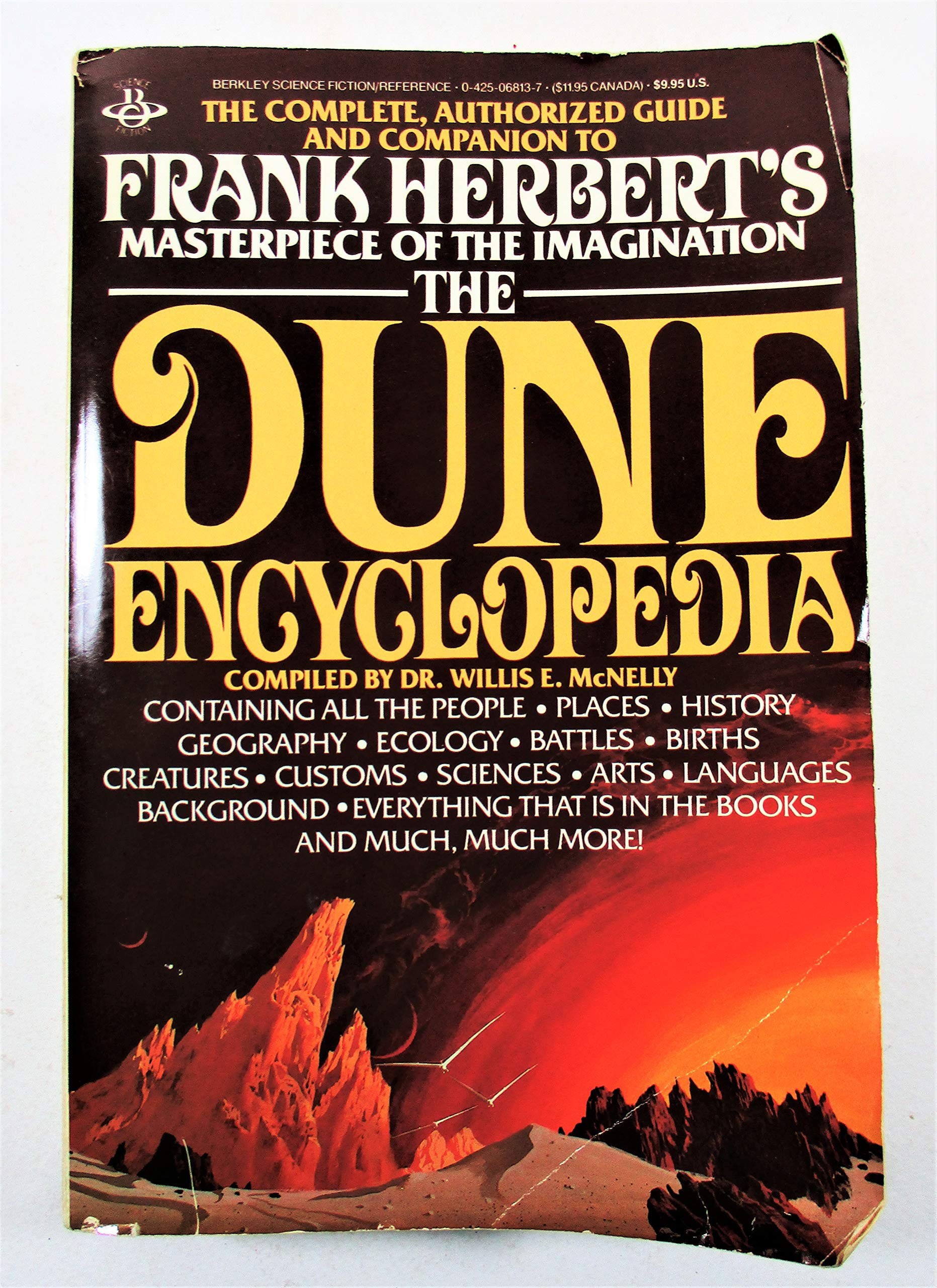

When David Lynch’s Hollywood version of Dune opened in theaters in 1984, Universal Studios distributed a printed a glossary to keep its audiences from getting confused. They got confused anyway, in part because of the film’s having been hollowed out in editing, and in part because the sheer elaborateness of Frank Herbert’s alternate reality poses potentially insurmountable challenges to faithful adaptation. Even many of the original Dune novels’ readers needed more help than a couple pages of definitions could offer. Luckily for them, the same year that saw the release of Lynch’s Dune also saw the publication of The Dune Encyclopedia, authorized by Herbert himself.

“Here is a rich background (and foreground) for the Dune Chronicles, including scholarly bypaths and amusing sidelights,” Herbert writes in the book’s introduction. “Some of the contributions are sure to arouse controversy, based as they are on questionable sources.” He couldn’t have known how right he was. Today The Dune Encyclopedia stands as what Inverse’s Ryan Britt calls “the most controversial Dune book ever”; long out of print, it may well also be the most expensive, with a current Amazon price of $1,300 in hardcover and $833 in paperback. (You can also find it online, at the Internet Archive.)

Still, The Dune Encyclopedia has its appreciators, not least the director of the latest (and most successful) cinematic attempt to realize Herbert’s vision. As Brit tells it, “an anonymous (though previously reliable) source stated that Denis Villeneuve is a big fan of The Dune Encyclopedia. But when he tried to plant references to the book in the new film, his ‘hand was slapped by the estate.’ ” The reason seems to involve the Encyclopedia’s conflicts with the novels: not those written by Herbert himself but, according to the Dune Wiki, “the later two prequel trilogies and sequel duology written after Frank Herbert’s death by Brian Herbert (Frank Herbert’s son) and Kevin J. Anderson, which they state complete the original series.”

Though co-signed by the The Dune Encyclopedia’s main author, literary scholar Willis E. McNelly, Brian Herbert and Kevin J. Anderson’s letter declaring the work’s de-canonization omits the fact “that the Encyclopedia is and always was a fallible in-universe document that openly misrepresents known history and adds historical embellishments.” It is, in other words, a book about Dune as well as a part of Dune. Not every book in our reality offers a perfectly true account of history, of course, and the same holds for the reality Frank Herbert created. This form implies the continuing possibility of expanding Dune’s literary universe by writing the books that exist within it, not just encyclopedias and scripture but, say epic sci-fi novels as well. What fan, after all, wouldn’t want to read the Dune of Dune?

Related content:

Rare Book Featuring the Concept Art for Jodorowsky’s Dune Goes Up for Auction (1975)

The Glossary Universal Studios Gave Out to the First Audiences of David Lynch’s Dune (1984)

The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction: 17,500 Entries on All Things Sci-Fi Are Now Free Online

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.