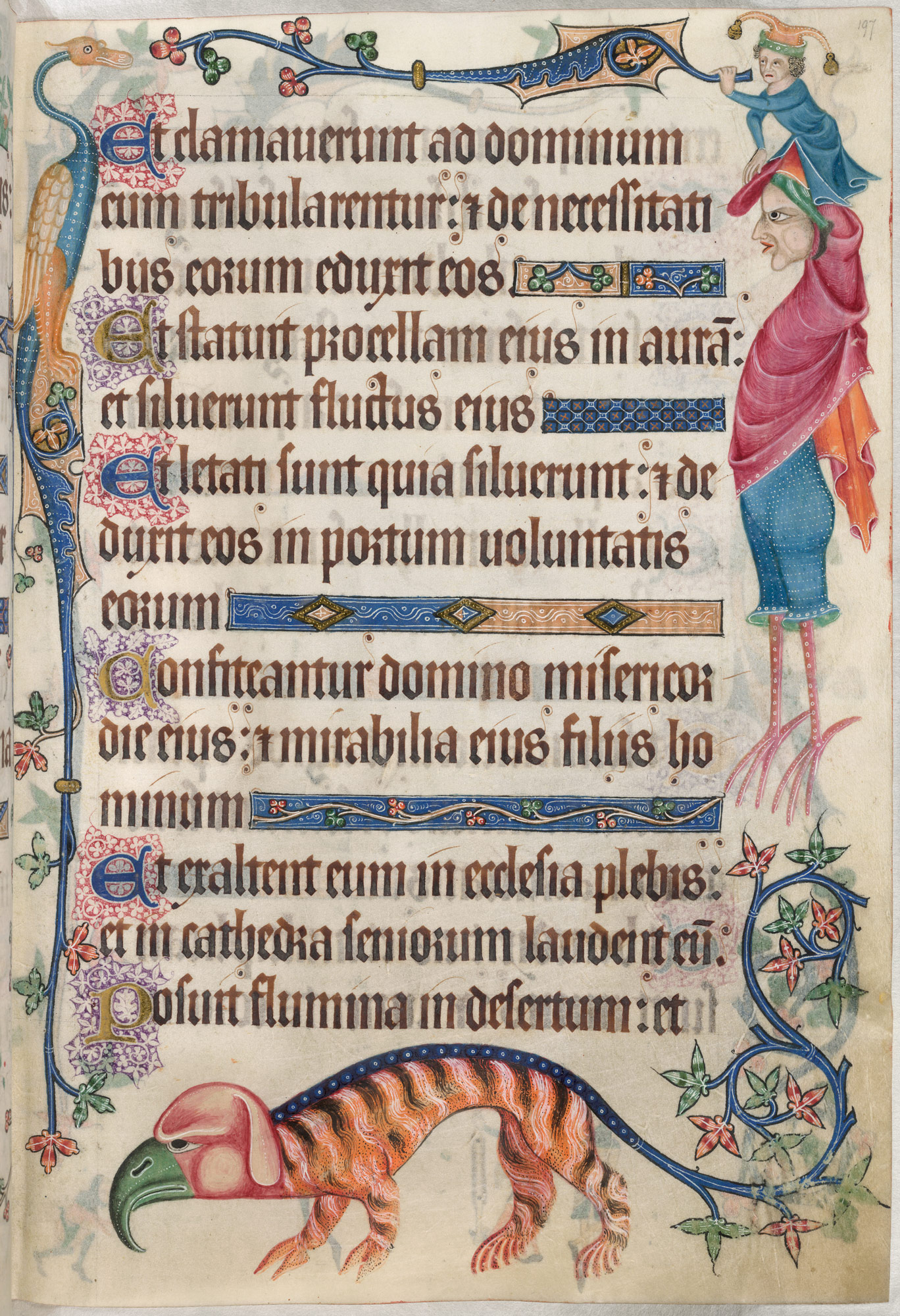

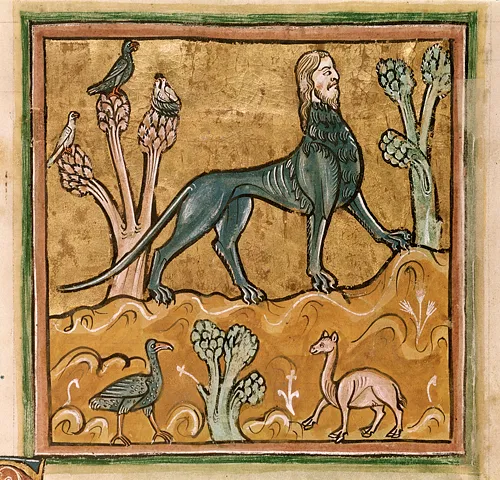

When we speak of a “lost art,” we do not always mean that humans have forgotten certain production methods. Modern craftspeople can recover or reasonably approximate old techniques and materials, and produce artifacts that can be passed off as authentic by the unscrupulous. The spirit of the thing, however, can never be recovered. Try as they might, scholars and conservators will never be able to enter the mind of a Medieval scribe or manuscript illuminator. Their social world has disappeared into a distant mist; we can only dimly guess at what their lives were like.

Thus, for many years, the reception of Hieronymus Bosch — the bizarre fantasist from the Netherlands whose visions of Earth, Heaven, and Hell have amused and terrified viewers — stressed the proto-Surrealism of his work, assuming he must have had other intentions than proselytizing.

Most recent interpretation, however, has pulled in the other direction, stressing the degree to which Bosch and his contemporaries believed in a universe that was exactly as weird as he depicted it, no exaggeration necessary; emphasizing how Bosch felt an urgent need to spare viewers of his work from the fates he showed in his art.

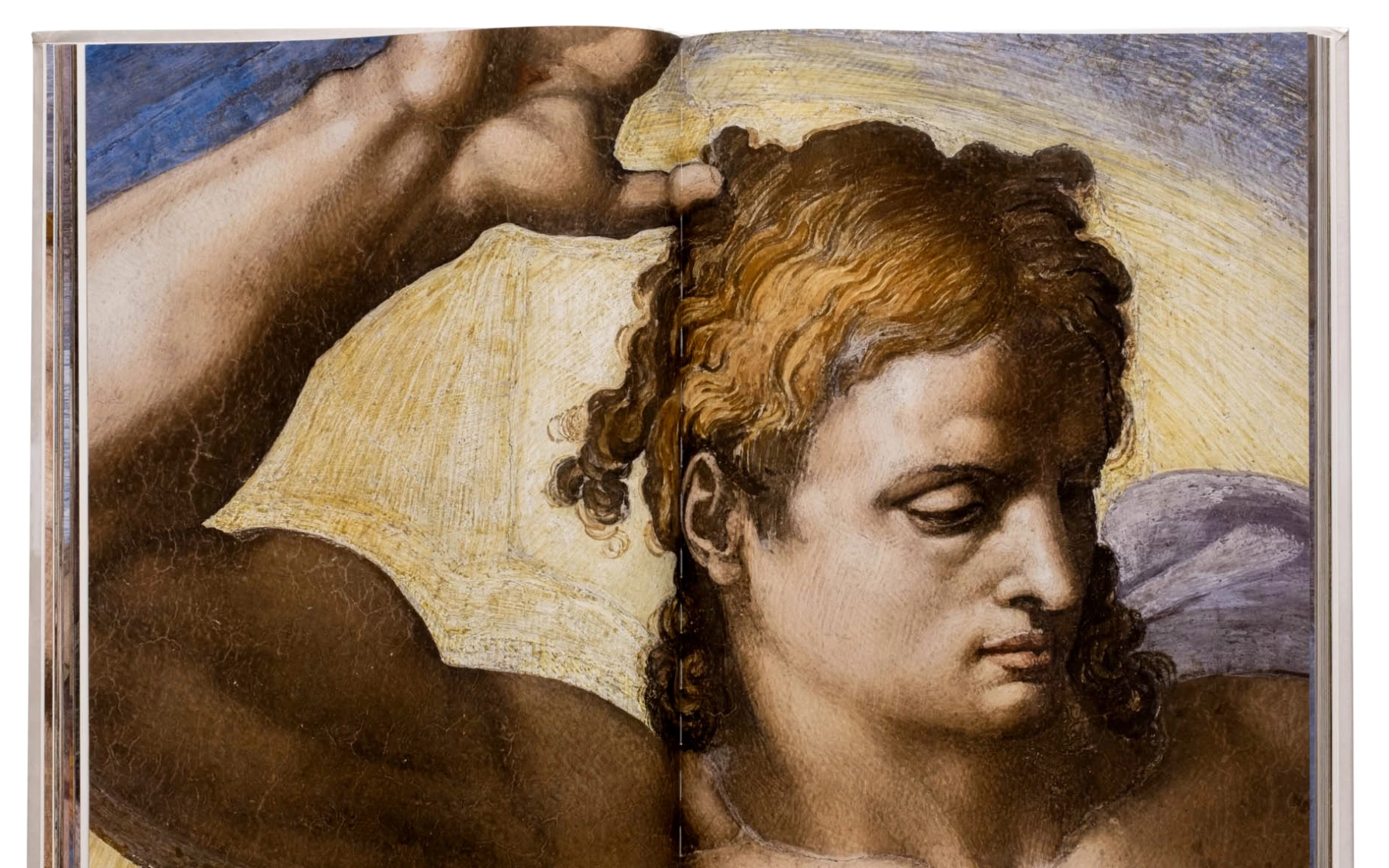

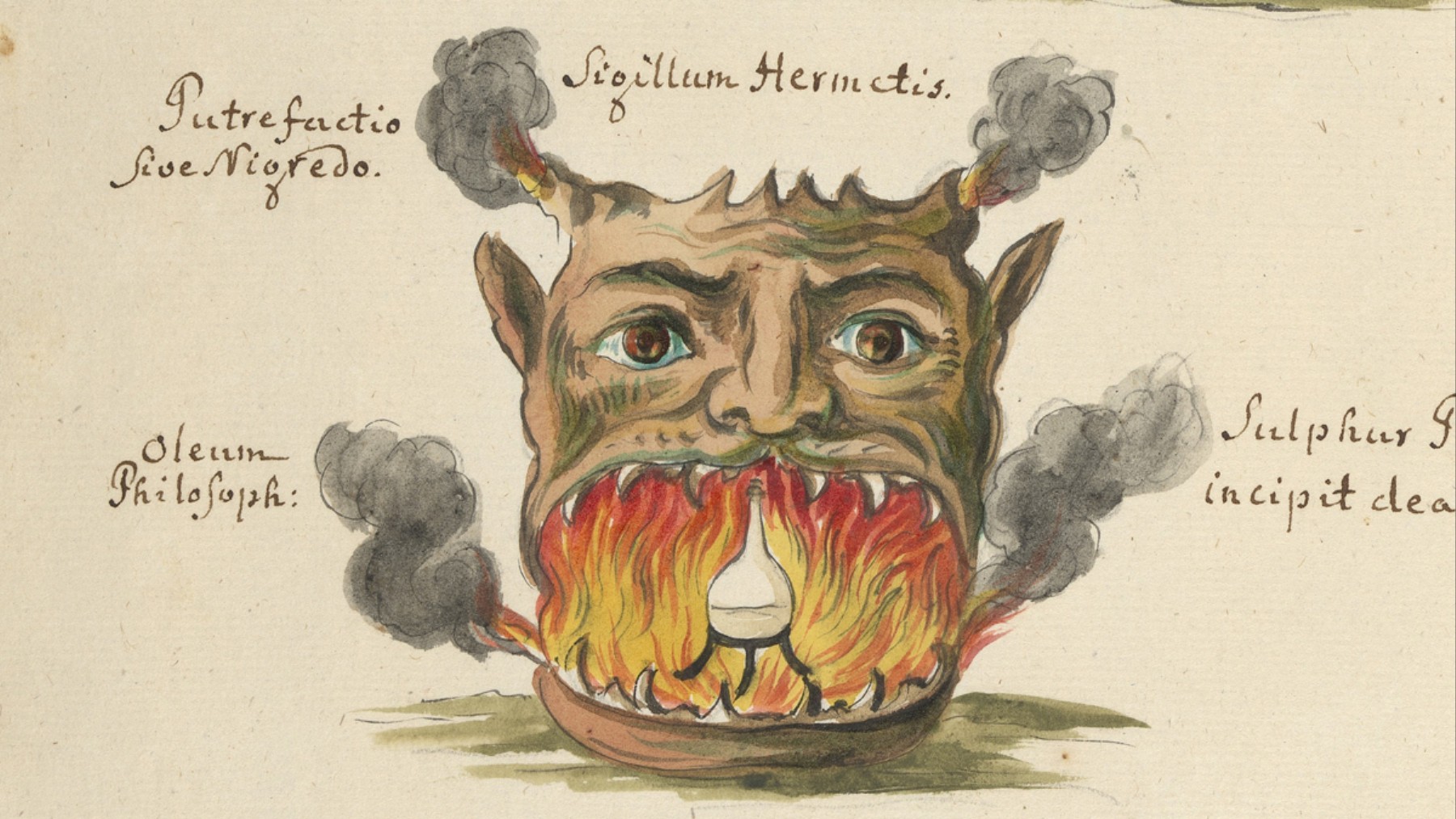

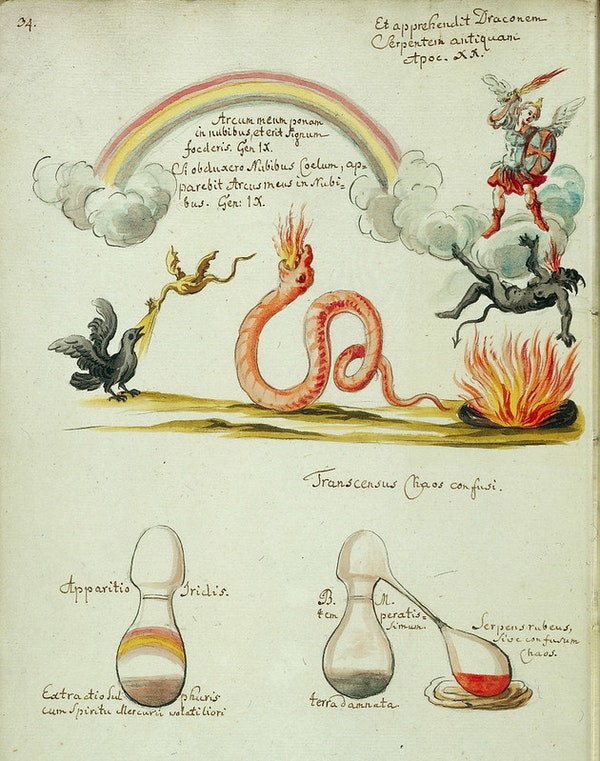

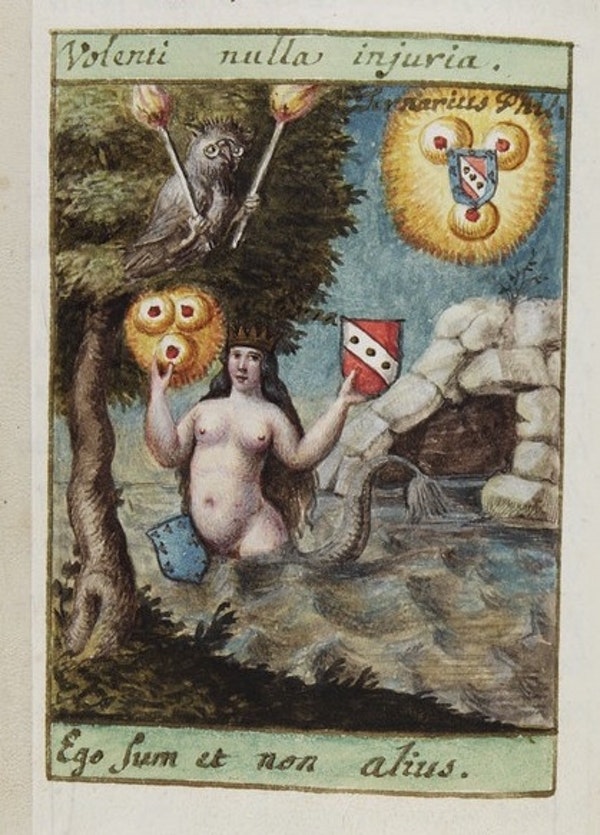

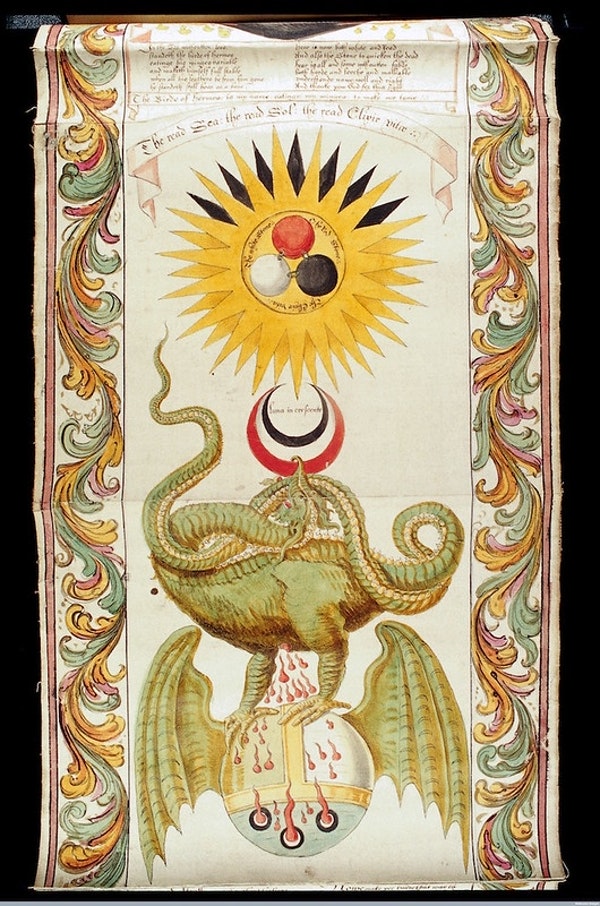

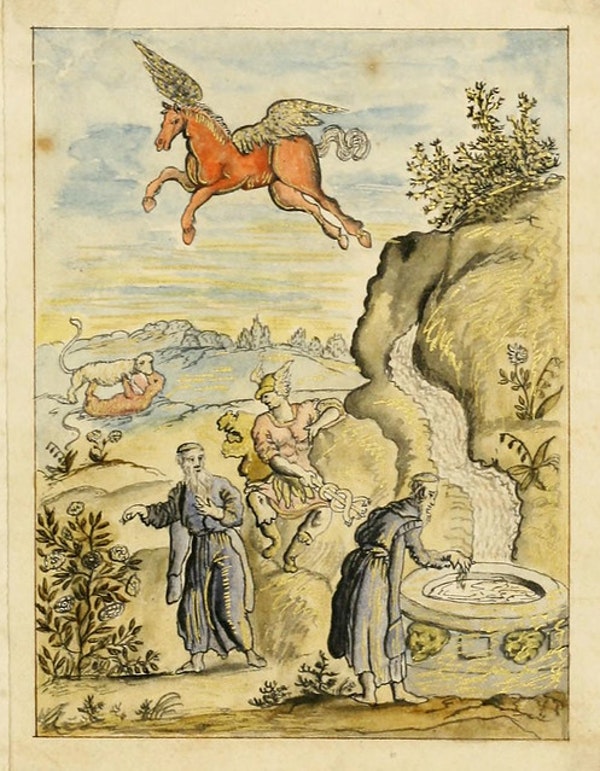

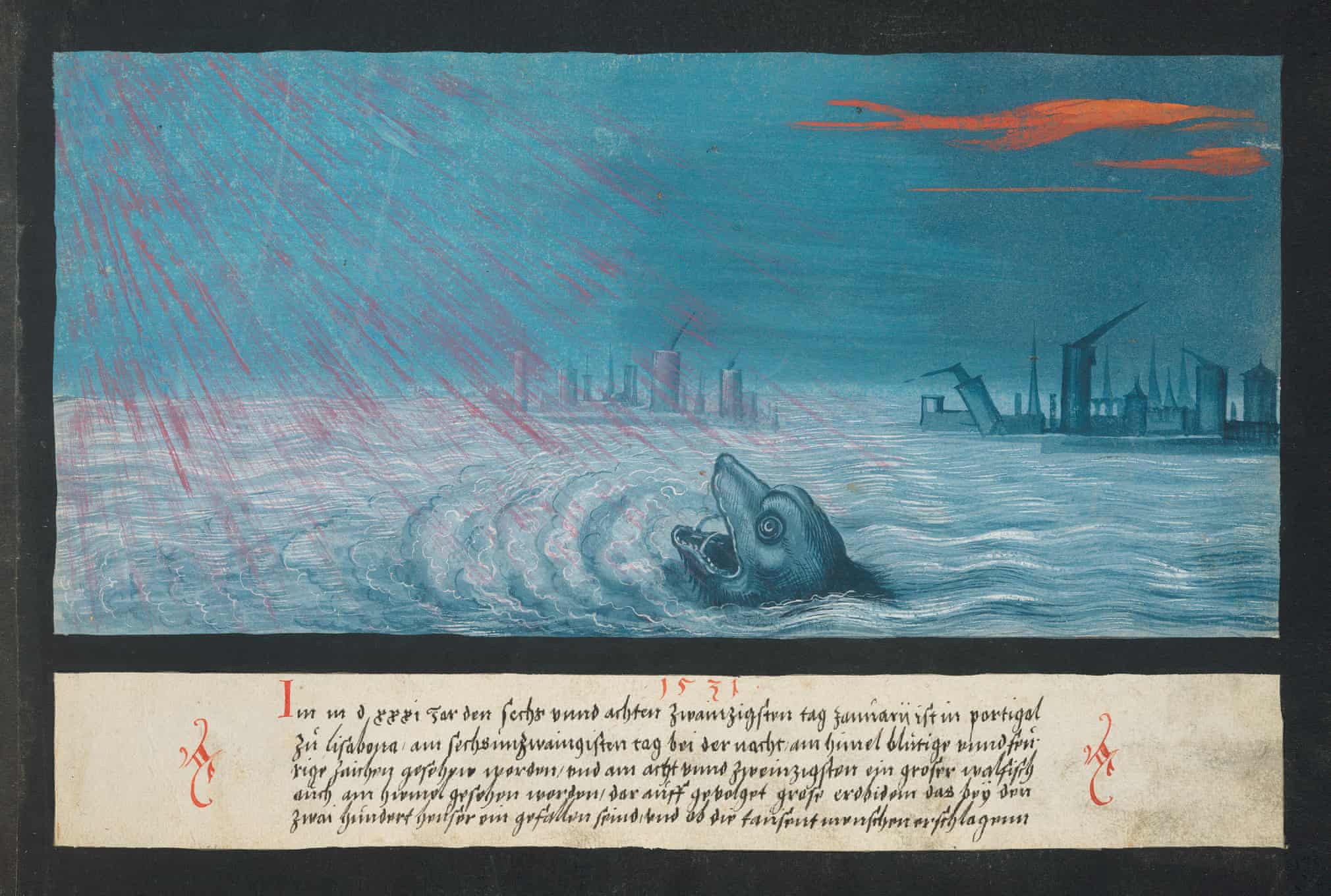

What passed through the mind of the illuminator of the manuscript shown here, the Augsburg Book of Miraculous Signs? We can never know. At best, scholars have settled on a name — artist and printmaker Hans Burgkmair the Younger — though little is known about him And we have a date, 1552, when this “curious and lavishly illustrated manuscript appeared in the Swabian Imperial Free city of Augsburg, then a part of the Holy Roman Empire, located in present-day Germany,” Maria Popova writes at the Marginalian. In the video at the top from Hochelaga, you can learn more about the “bizarre text” and the “meaning behind its unique contents” and “scenes of calamity and chaos.”

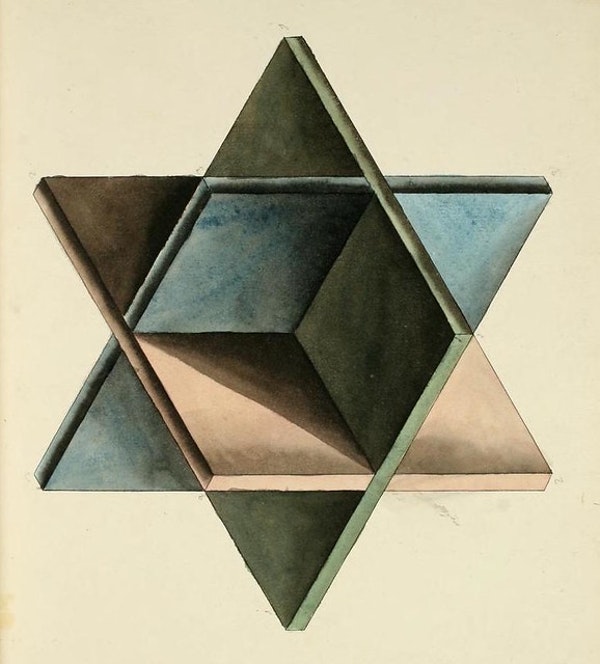

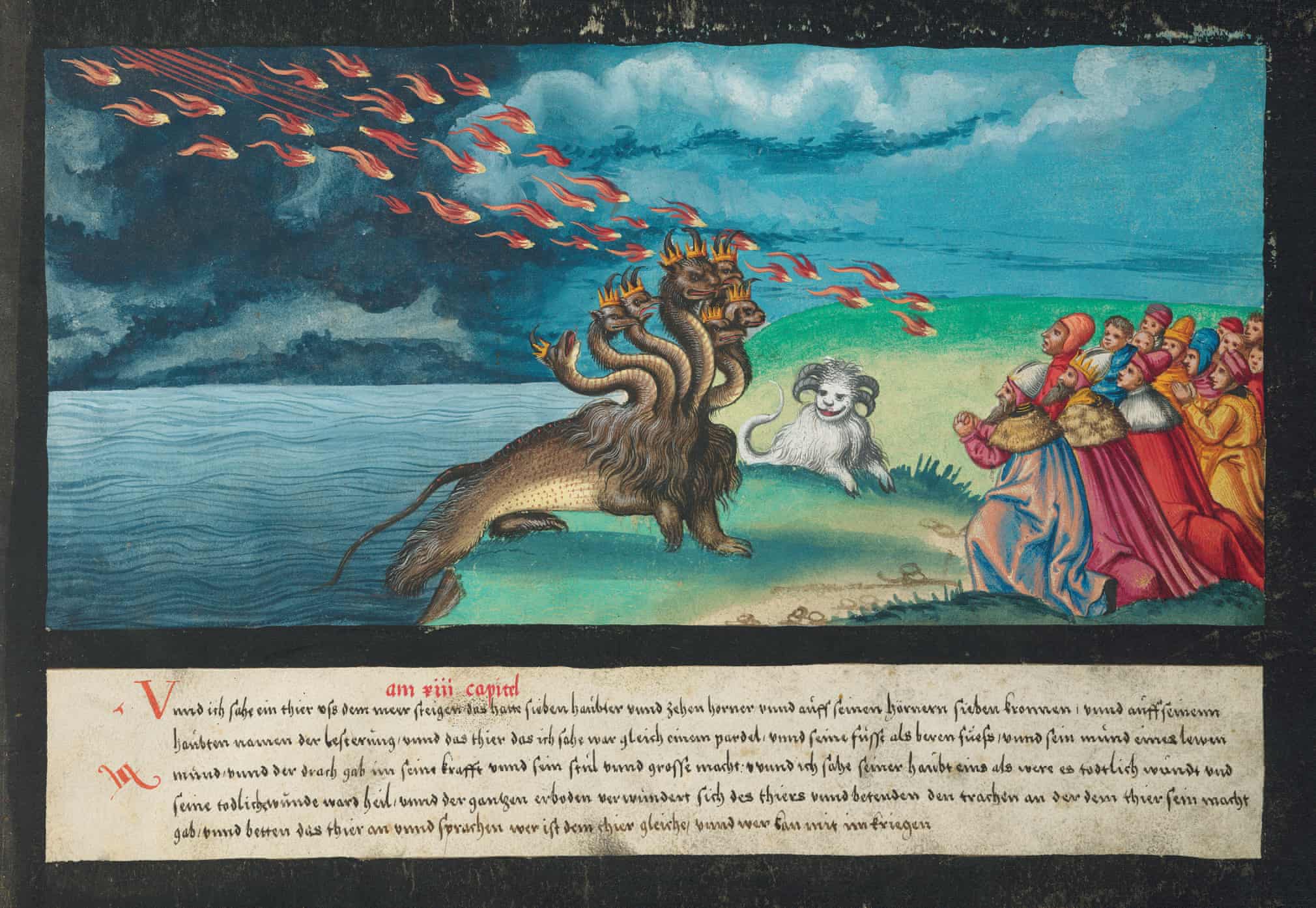

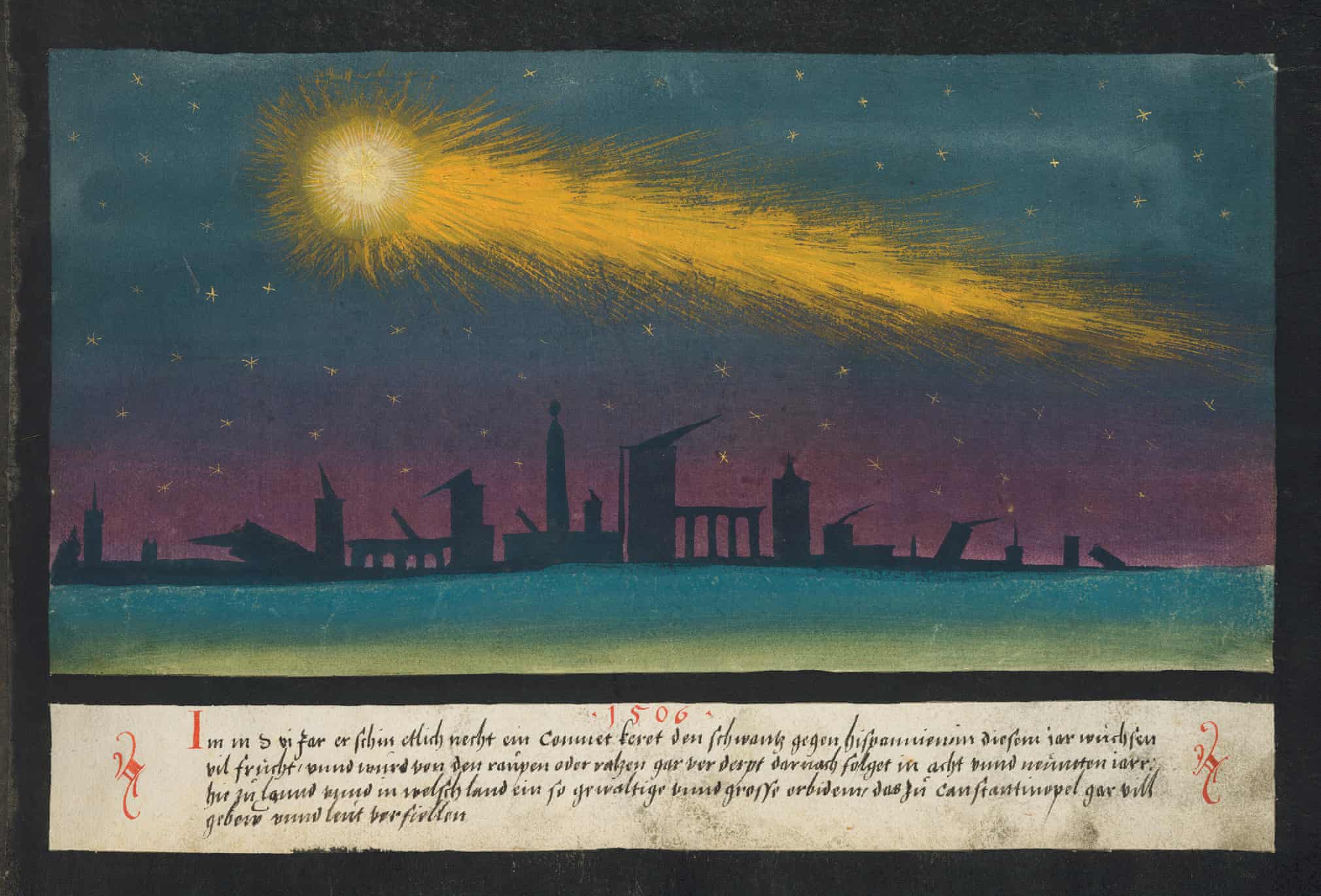

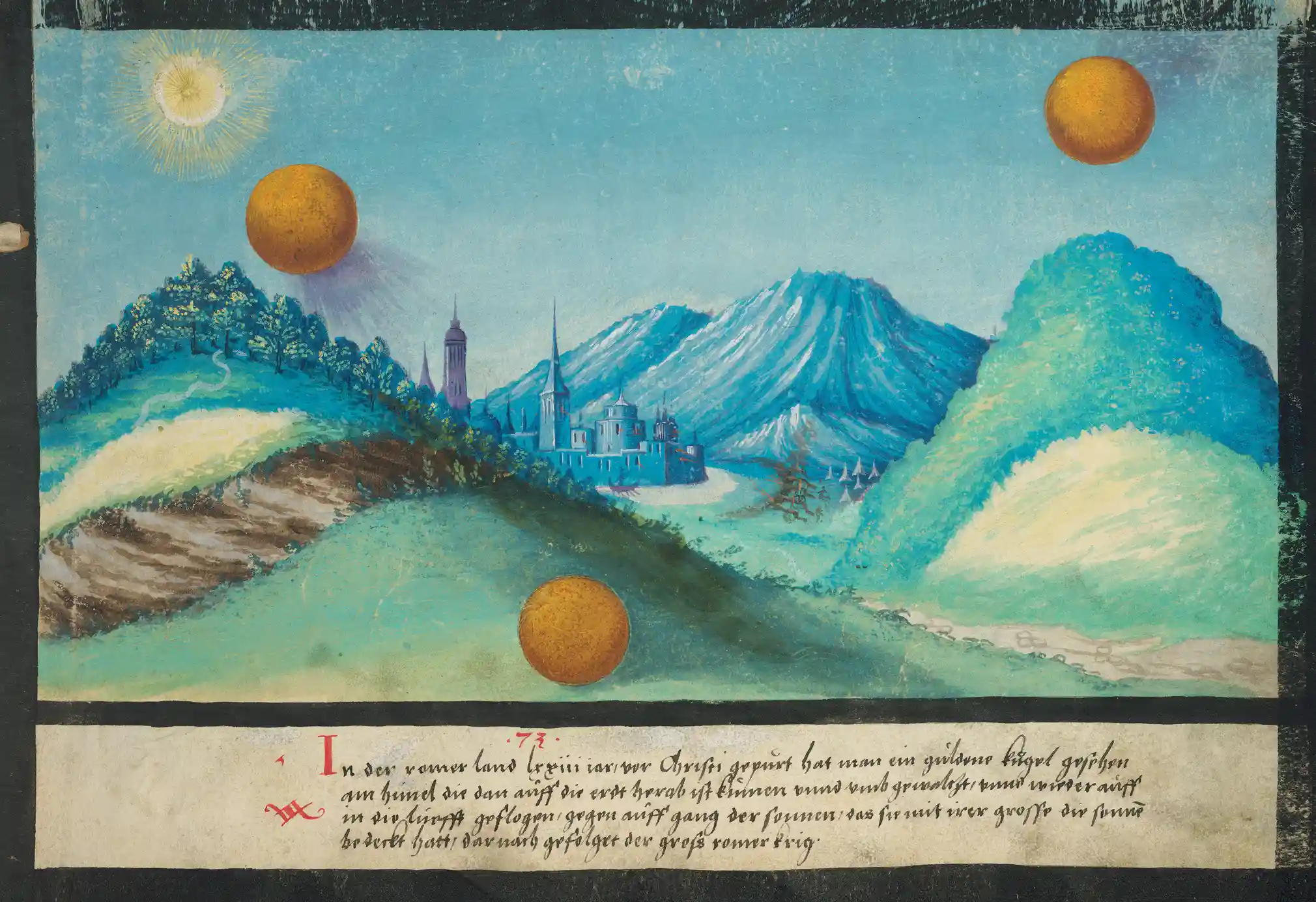

The strange book presents “in remarkable detail and wildly imaginative artwork, Medieval Europe’s growing obsessions with signs sent from ‘God,’ ” Popova writes, “a testament to the basic human propensity for magical thinking.” More specifically, The Book of Miracles recounts a host of Biblical signs and wonders in chronological order: from the first book of the Old Testament to the spectacular end of the New. In-between are “hallucinatory accounts of classical and contemporary celestial phenomena,” Tim Smith-Laing writes at Apollo. “The manuscript comprises nothing less than a picture chronicle of the world’s past, present and future, in 192 miracles.”

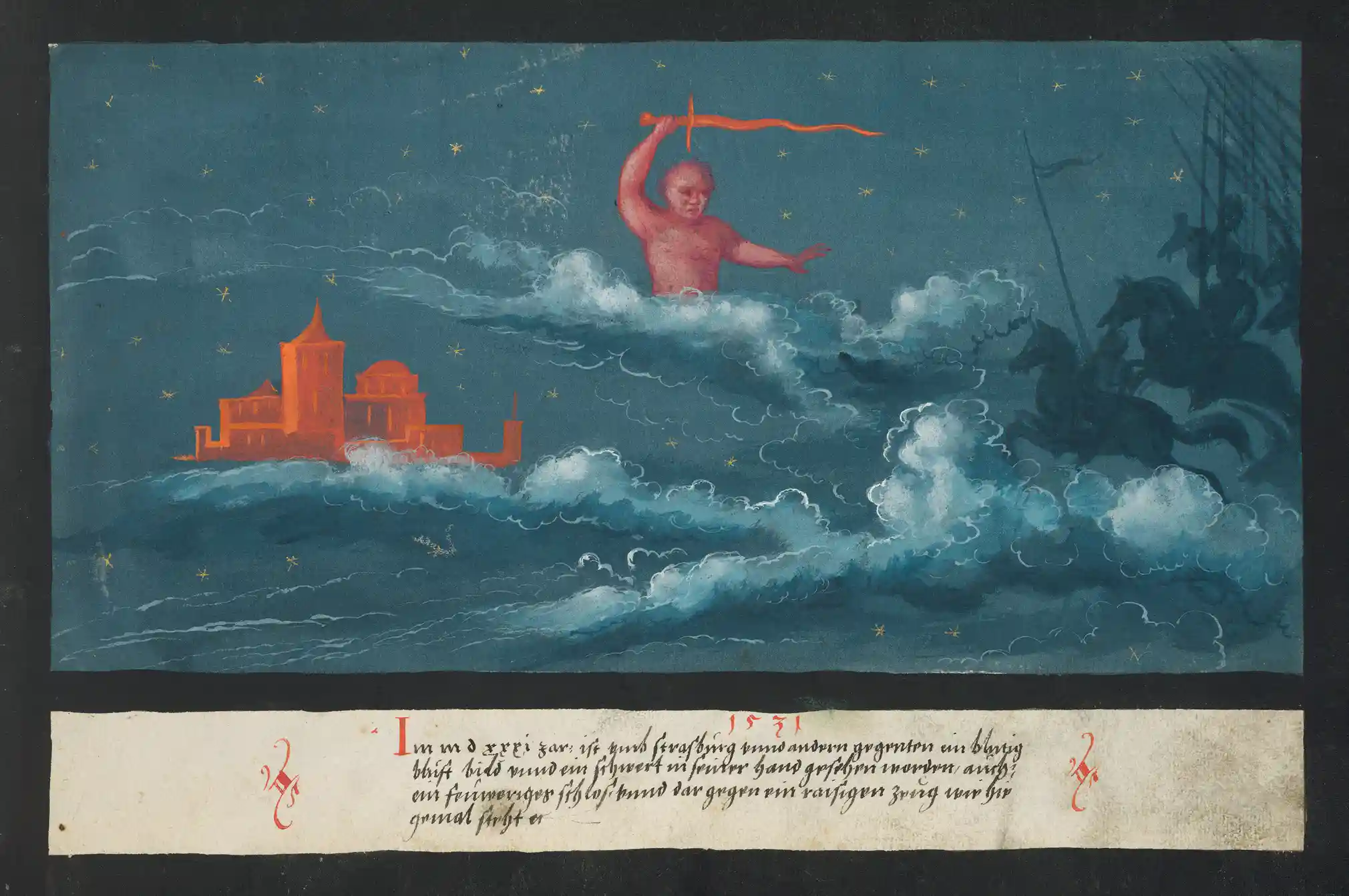

While Protestant Christianity condemned Medieval magic, “the recurrence of miracles in the Bible meant that the Protestant reformers of the sixteenth century could not reject such wonders as superstitions in the way they scorned Catholic beliefs,” Marina Warner writes at The New York Review of Books. German reformers were on high alert for the miraculous and ominous: “The sixteenth-century Zwinglian clergyman Johann Jakob Wick filled twenty-four albums with reports of such wonders in broadsheets and pamphlets,” seeing signs in the birth of a two-headed calf or “an unfortunate, flipper-handed infant.”

All of which is to say that we have little reason to doubt that the creator of The Book of Miracles meant the work as an earnest warning to its readers, although its wondrous images might look to us like proto-fantasy or sci-fi illustration. The book illustrates 1533 reports of flying dragons in Bohemia, an event, notes The Guardian, that “went on for several days, with over four hundred of them, both big and small, flying together.” It shows a comet appearing in 1506, one that stayed for several days and nights “and turned its tail towards Spain.” Thereby followed “a lot of fruit,” which was then “completely destroyed by caterpillars or rats,” then a violent earthquake in Constantinople.

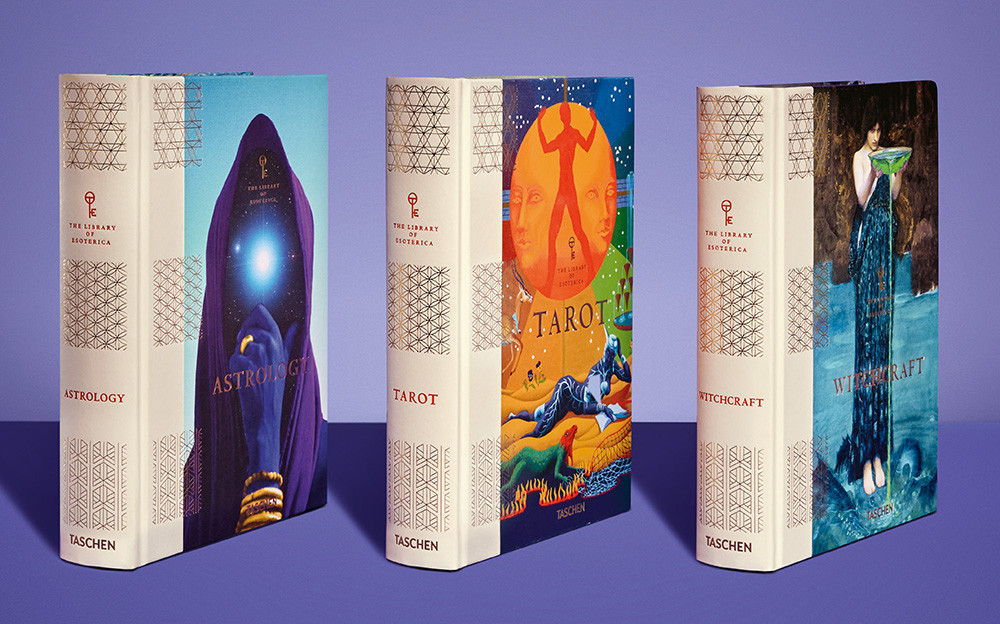

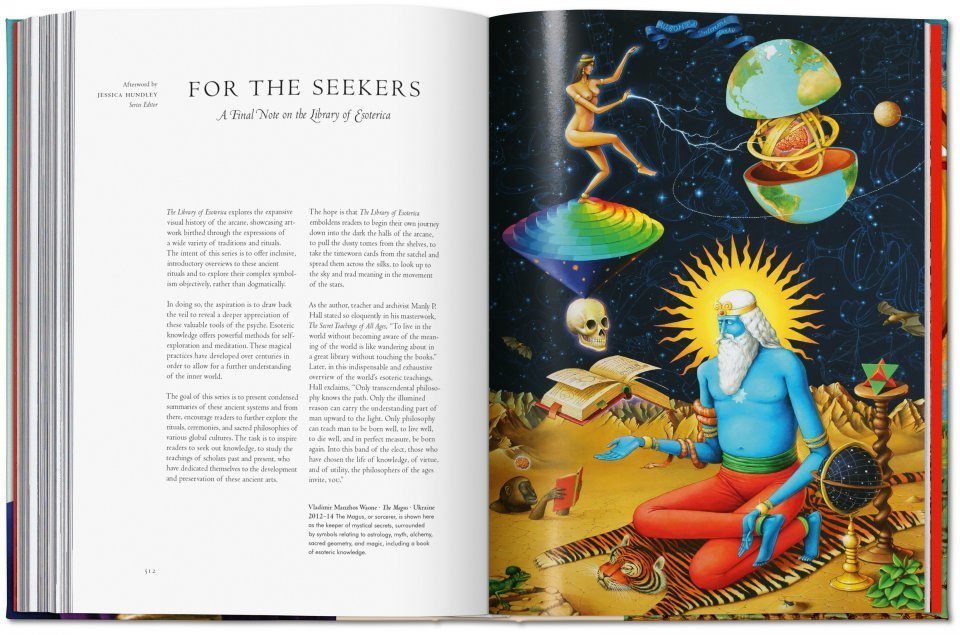

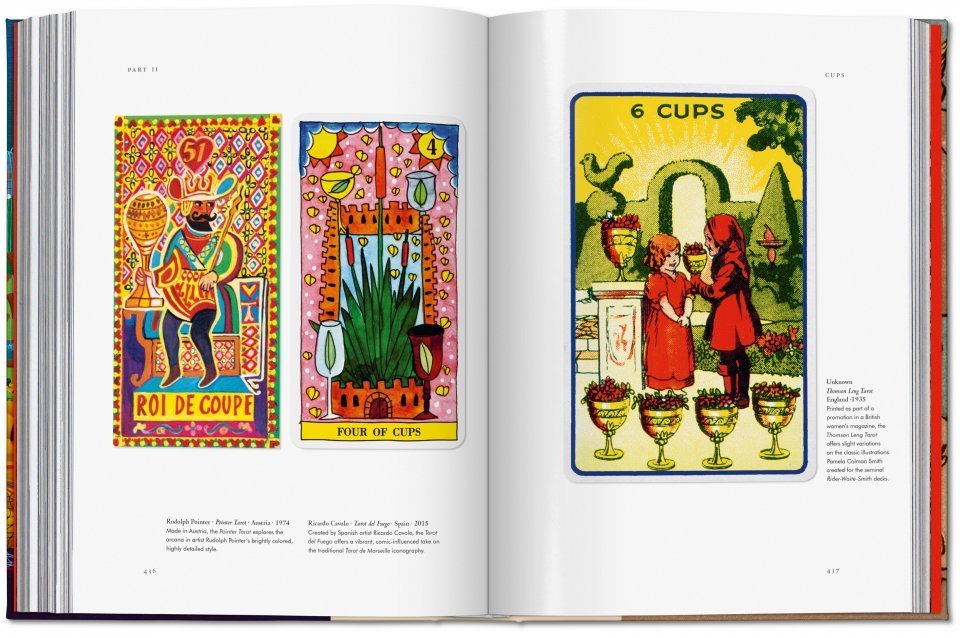

The very tenuous connection between disparate natural phenomena, the hearsay reports of magical happenings, you can read about all of these signs and wonders in a republished version by Taschen, in English, French, and German. It is, Popova writes, “a singular shrine to some of the most eternal of human hopes and fears, and, above all, our immutable longing for grace, for mercy, for the miraculous.” See more images from The Book of Miracles at The Guardian.

Related Content:

A Digital Archive of Hieronymus Bosch’s Complete Works: Zoom In & Explore His Surreal Art

The Medieval Masterpiece, the Book of Kells, Has Been Digitized and Put Online

160,000+ Medieval Manuscripts Online: Where to Find Them

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness