Hieronymus Bosch was born Jheronimus van Aken. We know precious little else about him, not even the year of his birth, which scholar Nicholas Baum guesses must have been right in the middle of the fifteenth century. But we do know that the artist was born in the Dutch town of ‘s‑Hertogenbosch, better known as Den Bosch, to which his assumed name pays tribute. It is thus to Den Bosch that Baum travels in the The Mysteries of Hieronymus Bosch, the 1983 BBC TV movie above, in search of clues to an interpretation of Bosch’s mysterious, grotesque, and sometimes hilarious paintings. What manner of place could produce an artistic mind capable of The Garden of Earthly Delights?

“My first reaction was disappointment,” Baum says of Den Bosch. “I wasn’t expecting such a very ordinary, very commercial, very provincial little town. I couldn’t for the life of me fit anybody as extraordinary as Bosch into a sleepy little place like this.” A hardworking everyday Dutchman might laugh at Baum’s English imagination having got away with him; perhaps he’d even quote his country’s well-worn proverb about normal human behavior being crazy enough.

Nevertheless, fueled by a near-lifelong fascination with Bosch’s fantastical and forbidding art, Baum goes deeper: quite literally deeper, in one case, descending to the dank cellar beneath the house where the artist grew up in order to take in “the authentic smell and feel of Bosch’s own day.”

Further insights come when Baum investigates Bosch’s membership in the Catholic fraternity of the Common Life. A few decades later, that same order would also educate northern Renaissance philosopher Erasmus, whose religiosity is well known. Bosch must have been no less pious, but for centuries that didn’t figure as thoroughly into the interpretation of his paintings as it might have. Focused on the vivid images of bacchanalia Bosch incorporated into his work, some speculated on his involvement in orgy-oriented secret societies. But Baum’s journey convinces him that Bosch was “a fierce and pious Christian” who painted with the goal of turning a gluttonous, wealth- and pleasure-obsessed humanity back toward the teachings of the Bible. And half a millennium later, it is his wildly imaginative renderings of sin that continue to compel us — as well as hold out the promise of further secrets yet unexplained.

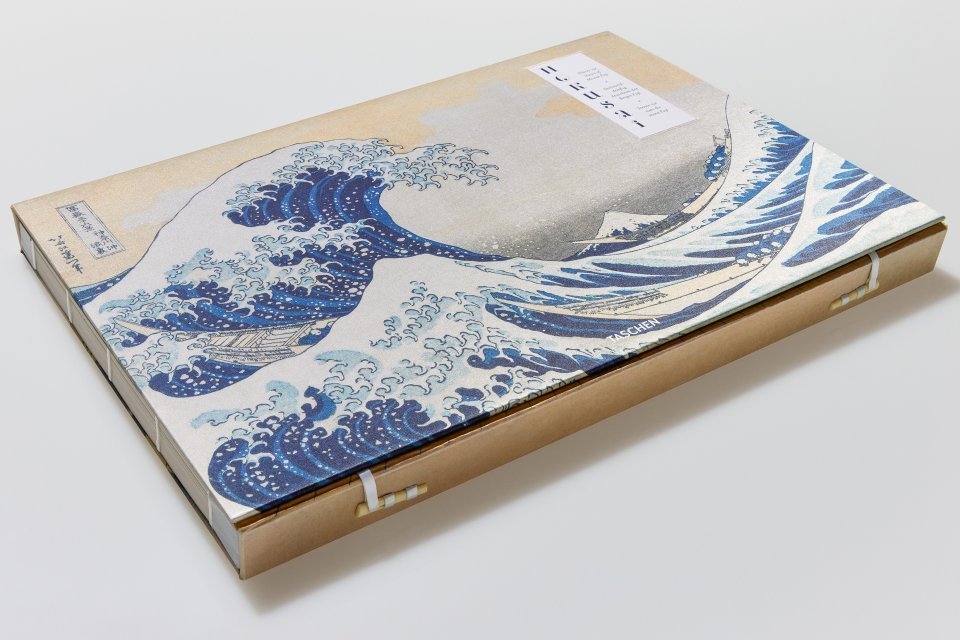

For anyone interested, Taschen now publishes an Bosch: The Complete Works, a beautiful and exhaustive exploration of the painter’s work. It includes a special chapter on The Garden of Earthly Delights.

Related Content:

The Meaning of Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights Explained

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.