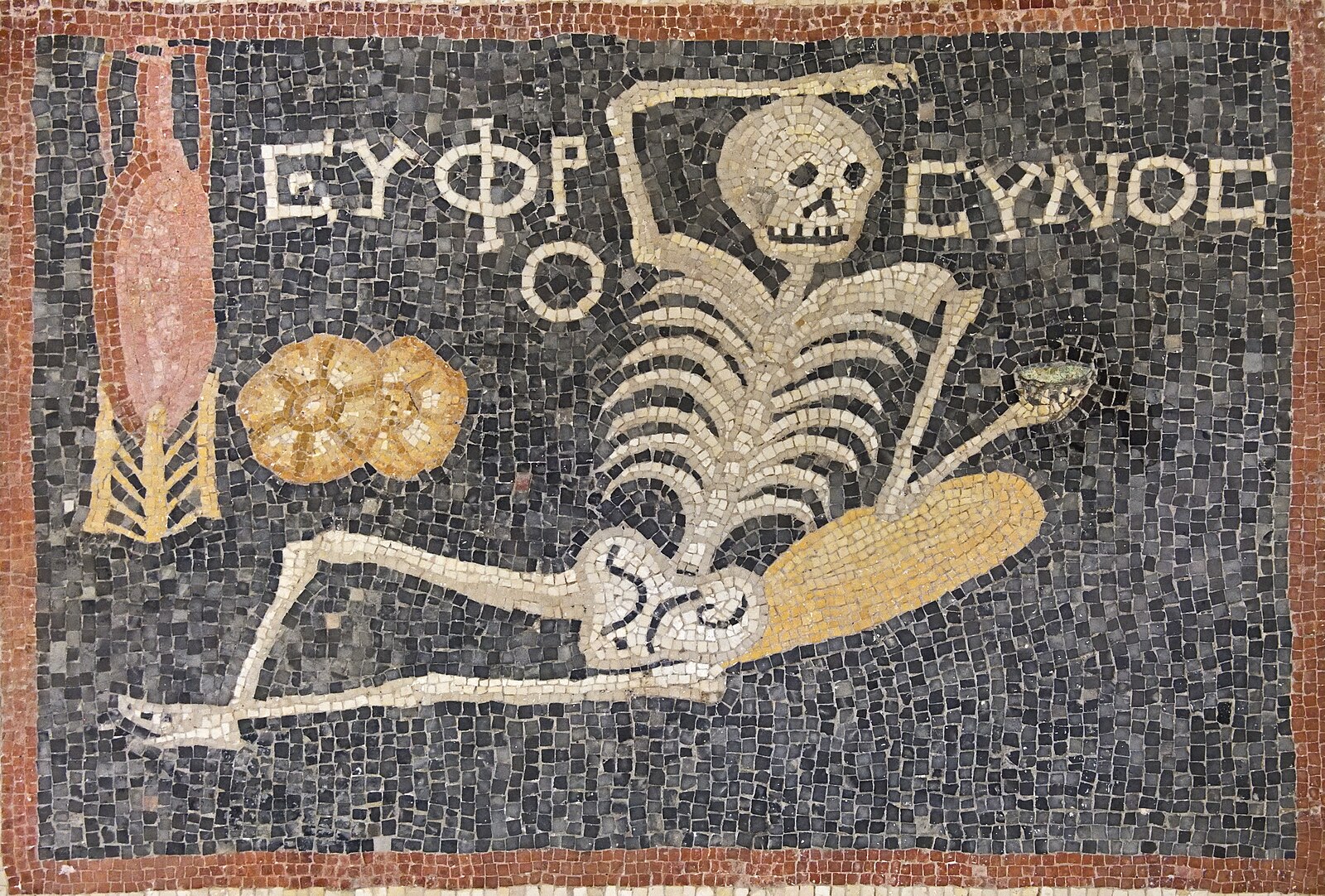

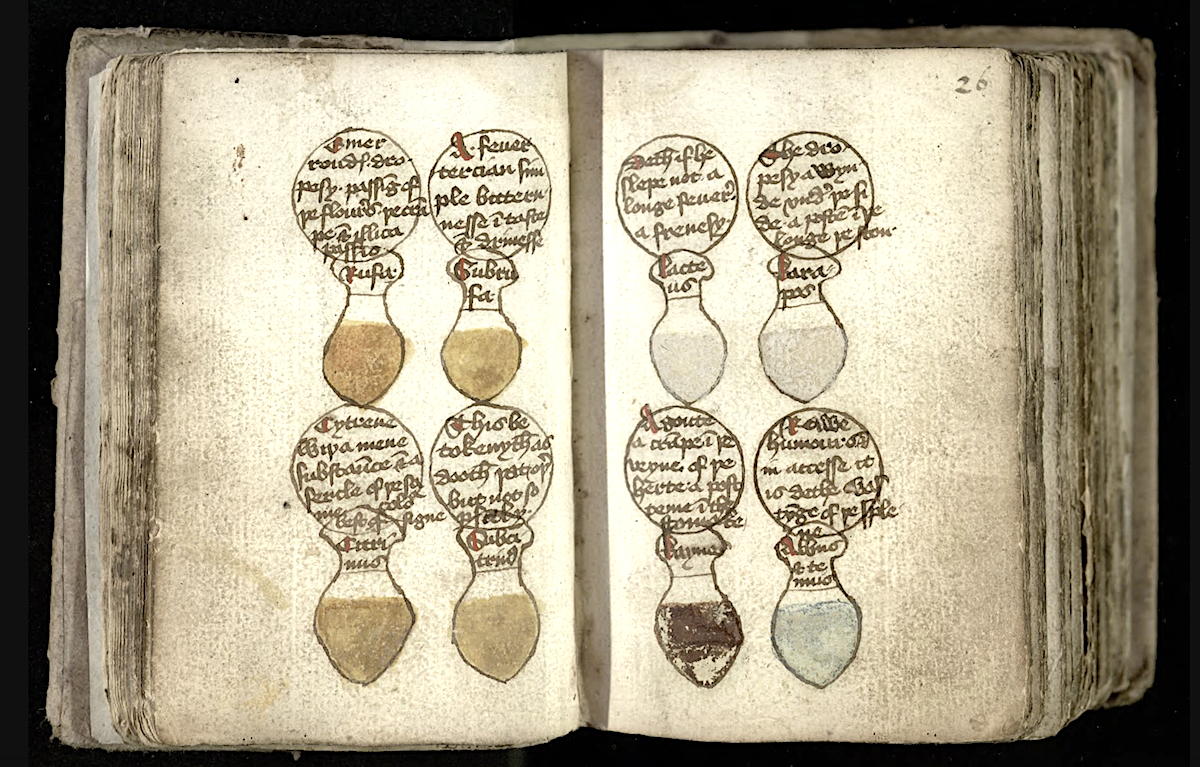

If any discussion of medieval medicine gets going, it’s only a matter of time before someone brings up leeches. And it turns out that the centrality of those squirming blood-suckers to the treatment of disease in the Middle Ages isn’t much overstated, at least judging by a look through Curious Cures. A Wellcome Research Resources Award-funded project of the University of Cambridge Libraries, it has recently finished conserving, digitizing, and making available online 190 manuscripts containing more than 7,000 pages of medieval medical recipes. These books contain a wealth of information even beyond the text on their pages: a multi-spectral imaging analysis of one of them, for example, revealed that it was once owned by a certain “Thomas Word, leche” — or leech, i.e., a healer who made intensive use of the tools you might imagine.

Not that the practice of medieval medicine came down to applying leeches and nothing more. In the manuscripts digitized by Curious Cures (which include not just strictly medical texts but also bibles, law texts, and books of hours), one finds a wonderland of dove feces, fox lungs, salted owl, eel grease, weasel testicles, quicksilver (i.e. mercury) — a wonderland for readers curious about medieval forms of knowledge, if not for the actual patients who had to undergo these dubious treatments.

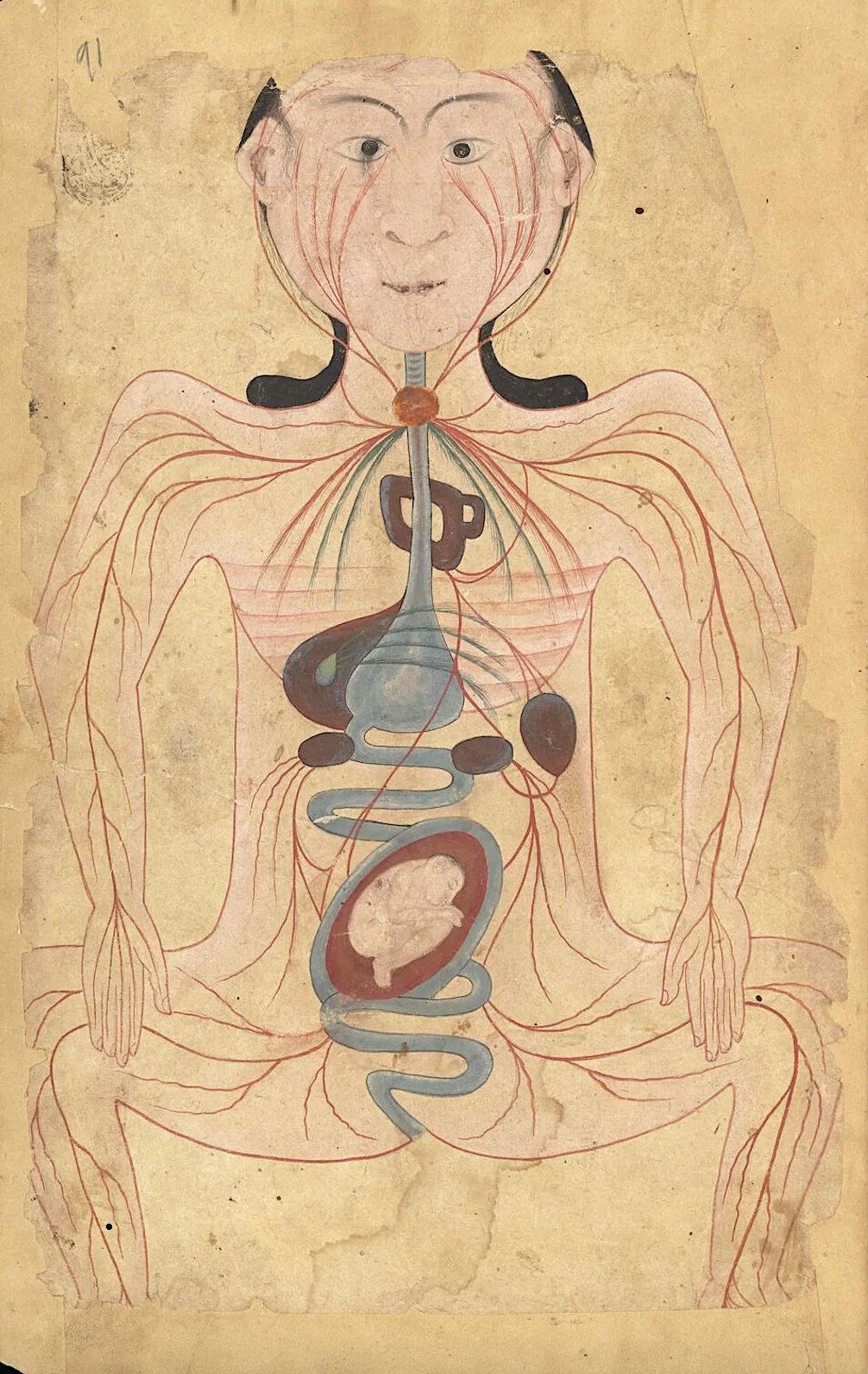

But as any scholar of the subject would be quick to remind us, medical documents in the Middle Ages may have wantonly mixed folk and “official” knowledge, but they were hardly repositories of pure superstition: rather, they represent the best efforts of intelligent people to understand their own bodies and the world they inhabited, within the dominant worldview of their time and place.

That was a time in which health was thought to be determined by the “four humors,” black bile, yellow bile, blood and phlegm; a time when certain parts of plants or animals were believed to be in “sympathetic” correspondence with certain parts of the human body; a time when repeatedly praying while clipping one’s fingernails, then burying those clippings in an elder tree, could plausibly cure a toothache. And now, it’s easier than ever to get a sense of what it must have been like, thanks to Curious Cures’ transcribed, translated, and searchable archive of all these manuscripts. The more outlandish remedies aside, what’s remarkable is how these books also acknowledge the importance of what we would now call a good night’s sleep, regular exercise, and a balanced, varied diet. Medievals may have understood their own health better than we imagine, but regardless, we’re probably not bringing back leechcraft anytime soon.

Related Content:

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.