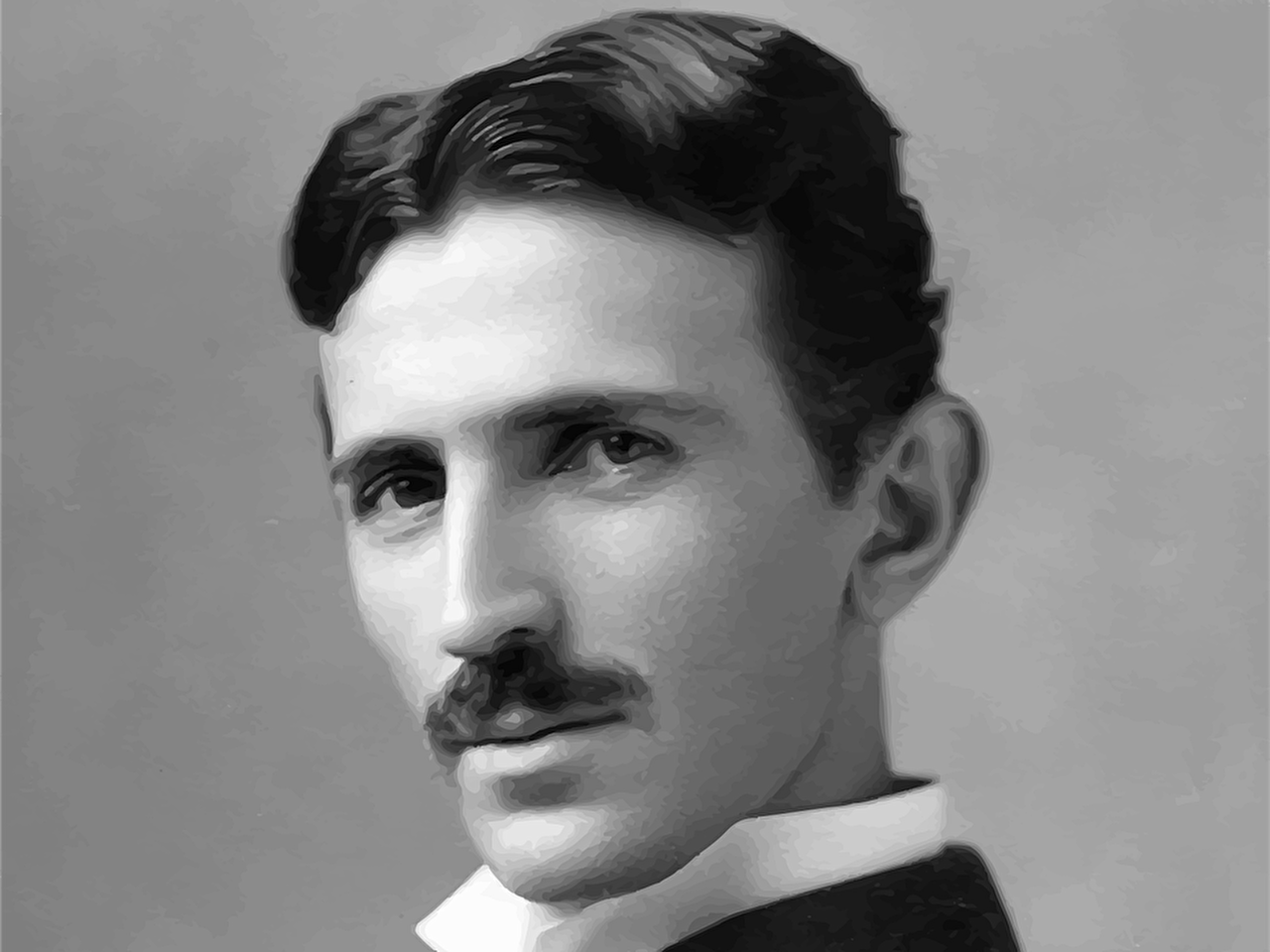

The fate of the visionary is to be forever outside of his or her time. Such was the life of Nikola Tesla, who dreamed the future while his opportunistic rival Thomas Edison seized the moment. Even now the name Tesla conjures seemingly wildly impractical ventures, too advanced, too expensive, or far too elegant in design for mass production and consumption. No one better than David Bowie, the pop artist of possibility, could embody Tesla’s air of magisterial high seriousness on the screen. And few were better suited than Tesla himself, perhaps, to extrapolate from his time to ours and see the technological future clearly.

Of course, this image of Tesla as a lone, heroic, and even somewhat tragic figure who fell victim to Edison’s designs is a bit of a romantic exaggeration. As even the editor of a 1935 feature interview piece in the now-defunct Liberty magazine wrote, Tesla and Edison may have been rivals in the “battle between alternating and direct current…. Otherwise the two men were merely opposites. Edison had a genius for practical inventions immediately applicable. Tesla, whose inventions were far ahead of the time, aroused antagonisms which delayed the fruition of his ideas for years.” One can in some respects see why Tesla “aroused antagonisms.” He may have been a genius, but he was not a people person, and some of his views, though maybe characteristic of the times, are downright unsettling.

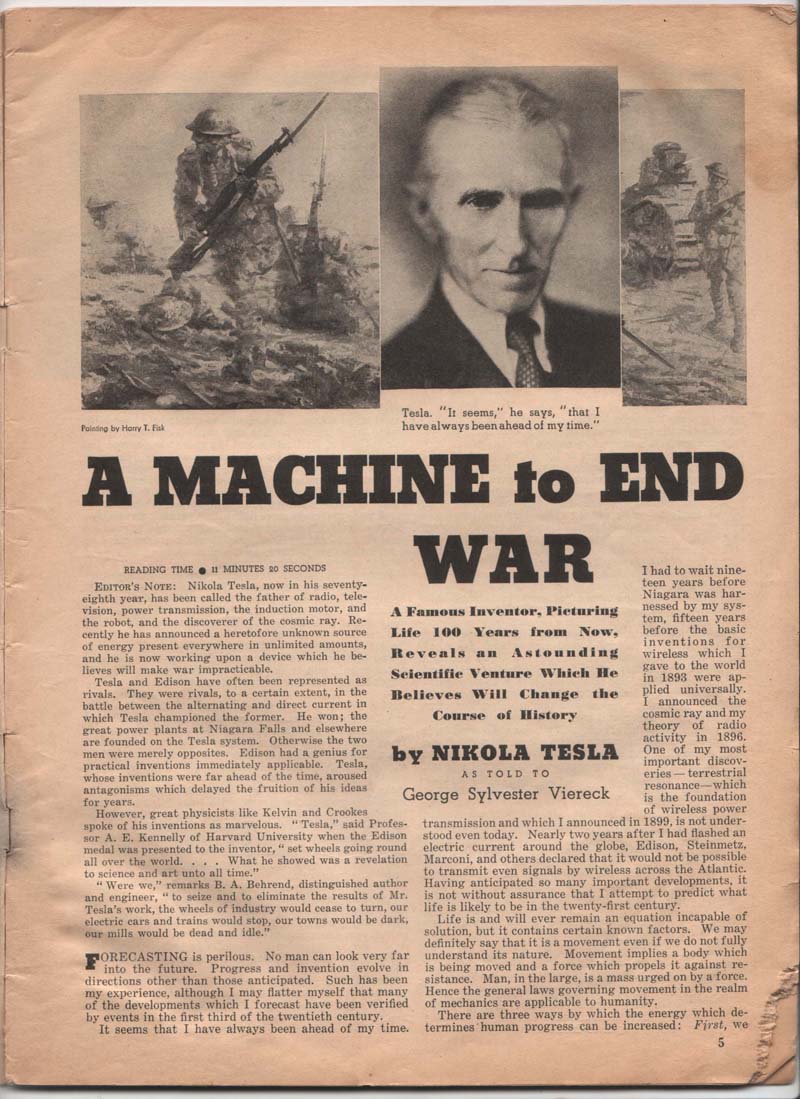

In the lengthy Liberty essay, “as told to George Sylvester Viereck” (a poet and Nazi sympathizer who also interviewed Hitler), Tesla himself makes the pronouncement, “It seems that I have always been ahead of my time.” He then goes on to enumerate some of the ways he has been proven right, and confidently lists the characteristics of the future as he sees it. No one likes a know-it-all, but Tesla refused to compromise or ingratiate himself, though he suffered for it professionally. And he was, in many cases, right. Many of his 1935 predictions in Liberty are still too far off to measure, and some of them will seem outlandish, or criminal, to us today. But some still seem plausible, and a few advisable if we are to make it another 100 years as a species. Tesla’s predictions include the following, which he introduces with the disclaimer that “forecasting is perilous. No man can look very far into the future.”

- “Buddhism and Christianity… will be the religion of the human race in the twenty-first century.”

- “The year 2100 will see eugenics universally established.” Tesla went on to comment, “no one who is not a desirable parent should be permitted to produce progeny. A century from now it will no more occur to a normal person to mate with a person eugenically unfit than to marry a habitual criminal.”

- “Hygiene, physical culture will be recognized branches of education and government. The Secretary of Hygiene or Physical Culture will be far more important in the cabinet of the President of the United States who holds office in the year 2025 than the Secretary of War.” Along with personal hygiene, Tesla included “pollution” as a social ill in need of regulation.

- “I am convinced that within a century coffee, tea, and tobacco will be no longer in vogue. Alcohol, however, will still be used. It is not a stimulant but a veritable elixir of life.”

- “There will be enough wheat and wheat products to feed the entire world, including the teeming millions of China and India.” (Tesla did not foresee the anti-gluten mania of the 21st century.)

- “Long before the next century dawns, systematic reforestation and the scientific management of natural resources will have made an end of all devastating droughts, forest fires, and floods. The universal utilization of water power and its long-distance transmission will supply every household with cheap power.” Along with this optimistic prediction, Tesla foresaw that “the struggle for existence being lessened, there should be development along ideal rather than material lines.”

Tesla goes on to predict the elimination of war, “by making every nation, weak or strong, able to defend itself,” after which war chests would be diverted to funding education and research. He then describes—in rather fantastical-sounding terms—an apparatus that “projects particles” and transmits energy, enabling not only a revolution in defense technology, but “undreamed of results in television.” Tesla diagnoses his time as one in which “we suffer from the derangement of our civilization because we have not yet completely adjusted ourselves to the machine age.” The solution, he asserts—along with most futurists, then and now—“does not lie in destroying but in mastering the machine.” As an example of such mastery, Tesla describes the future of “automatons” taking over human labor and the creation of “a thinking machine.”

Matt Novak at the Smithsonian has analyzed many of Tesla’s claims, interpreting his predictions about “hygiene and physical culture” as a foreshadowing of the EPA and discussing Tesla’s work in robotics (“Today,” Tesla proclaimed, “the robot is an accepted fact”). The Liberty article was not the first time Tesla had made large-scale, public predictions about the century to come and beyond. In 1926, Tesla gave an interview to Collier’s magazine in which he more or less accurately foresaw smartphones and wireless telephony and computing:

When wireless is perfectly applied the whole earth will be converted into a huge brain, which in fact it is…. We shall be able to communicate with one another instantly, irrespective of distance. Not only this, but through television and telephony we shall see and hear one another as perfectly as though were face to face, despite intervening distances of thousands of miles; and the instruments through which we shall be able to do this will be amazingly simple compared with our present telephone. A man will be able to carry one in his vest pocket.

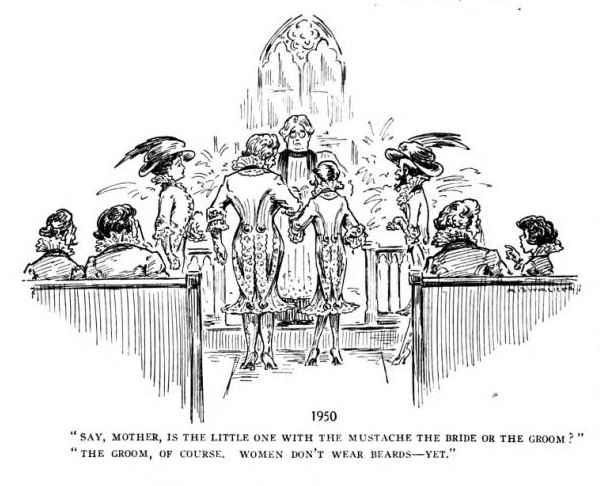

Telsa also made some odd predictions about fuel-less passenger flying machines “free from any limitations of the present airplanes and dirigibles” and spouted more of the scary stuff about eugenics that had come to obsess him late in life. Additionally, Tesla saw changing gender relations as the precursor of a coming matriarchy. This was not a development he characterized in positive terms. For Tesla, feminism would “end in a new sex order, with the female as superior.” (As Novak notes, Tesla’s misgivings about feminism have made him a hero to the so-called “men’s rights” movement.) While he fully granted that women could and would match and surpass men in every field, he warned that “the acquisition of new fields of endeavor by women, their gradual usurpation of leadership, will dull and finally dissipate feminine sensibilities, will choke the maternal instinct, so that marriage and motherhood may become abhorrent and human civilization draw closer and closer to the perfect civilization of the bee.”

It seems to me that a “bee civilization” would appeal to a eugenicist, except, I suppose, Tesla feared becoming a drone. Although he saw the development as inevitable, he still sounds to me like any number of current politicians who argue that society should continue to suppress and discriminate against women for their own good and the good of “civilization.” Tesla may be an outsider hero for geek culture everywhere, but his social attitudes give me the creeps. While I’ve personally always liked the vision of a world in which robots do most the work and we spend most of our money on education, when it comes to the elimination of war, I’m less sanguine about particle rays and more sympathetic to the words of Ivor Cutler.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2015.

via Smithsonian/Paleofuture

Related Content:

In 1900, Ladies’ Home Journal Publishes 28 Predictions for the Year 2000

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness