At the height of his fame, Charles Dickens could have commanded any illustrator he liked for his novels. But at the beginning of his literary career, it was he who was charged with accompanying the artist, not the other way around. His first serialized novel The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, better known as The Pickwick Papers, began as a series of comical “cockney sporting plates” by Robert Seymour. Honest enough to admit his ignorance of the cockney sporting life but shrewd enough to know an opportunity when he saw one, the young Dickens accepted the publisher’s request for stories meant to elaborate on the images.

Even then, Dickens possessed irrepressible talent as a popular storyteller, and it was his writing — which evidenced scant interest in adherence to the existing art — that made The Pickwick Papers into a great success, a mass-cultural phenomenon comparable to a hit sitcom avant la lettre.

187 years later there remains a whiff of scandal around this chapter of literary history, Seymour having committed suicide early in the serialization process the day after an argument with Dickens. Eventually the author found a permanent replacement for Seymour in Hablot Knight Browne, or Phiz, who would go on to provide the artwork for most of his novels.

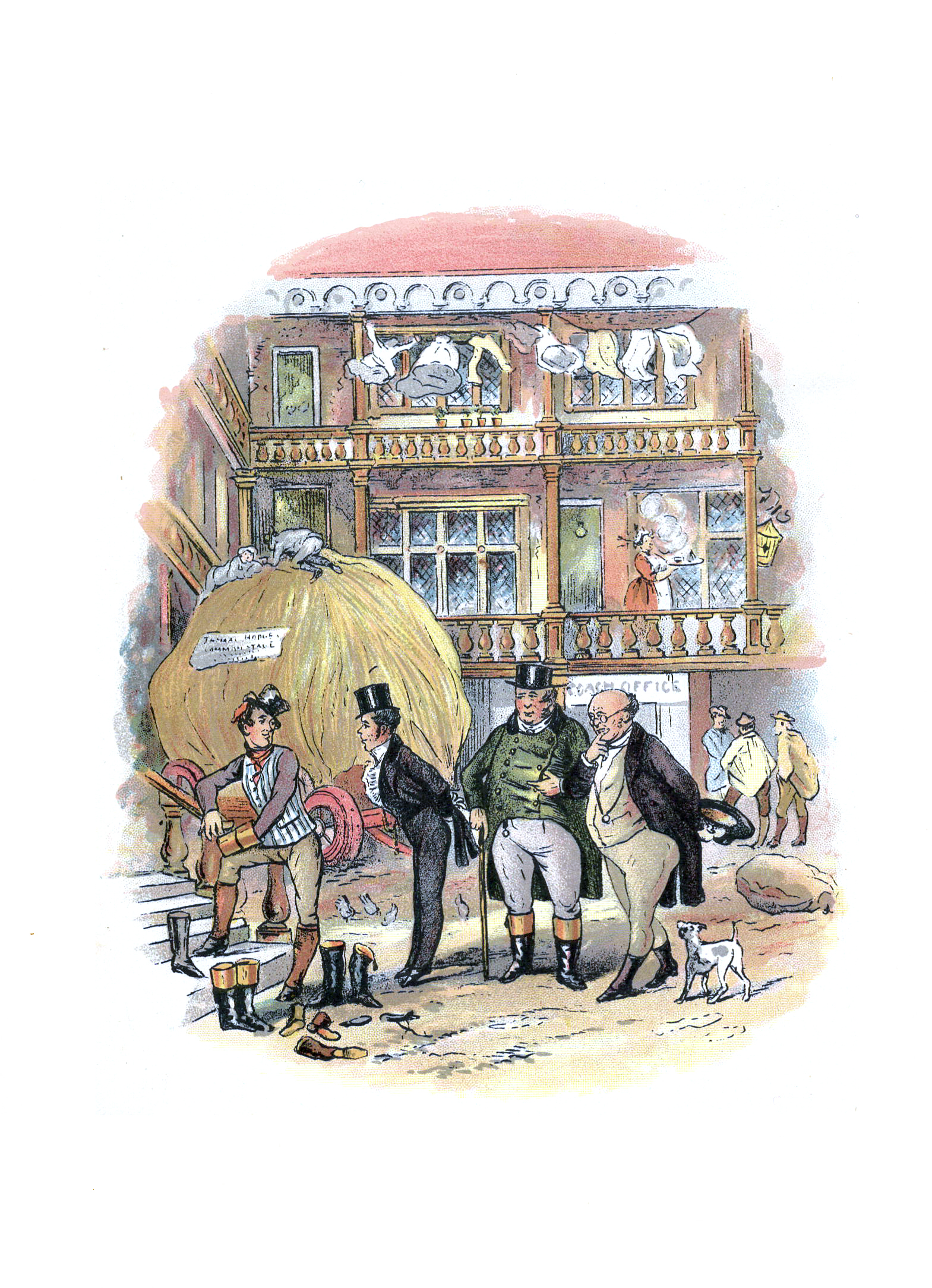

You can see all of Phiz’s work for Dickens at the Charles Dickens Illustrated Gallery, a project of Michael John Goodman, whom we’ve previously featured here on Open Culture for his Victorian Illustrated Shakespeare Archive (and his collection of AI-generated Shakespeare art). “The world of Dickens illustration is beset with poor reproductions of the source material, so for this project I have searched out what I consider to be some of the best editions that feature the original illustrations printed to a decent quality,” Goodman writes on his project’s About page. These tend to date from the early twentieth century and come with “colored frontispieces (which the original novels did not have).”

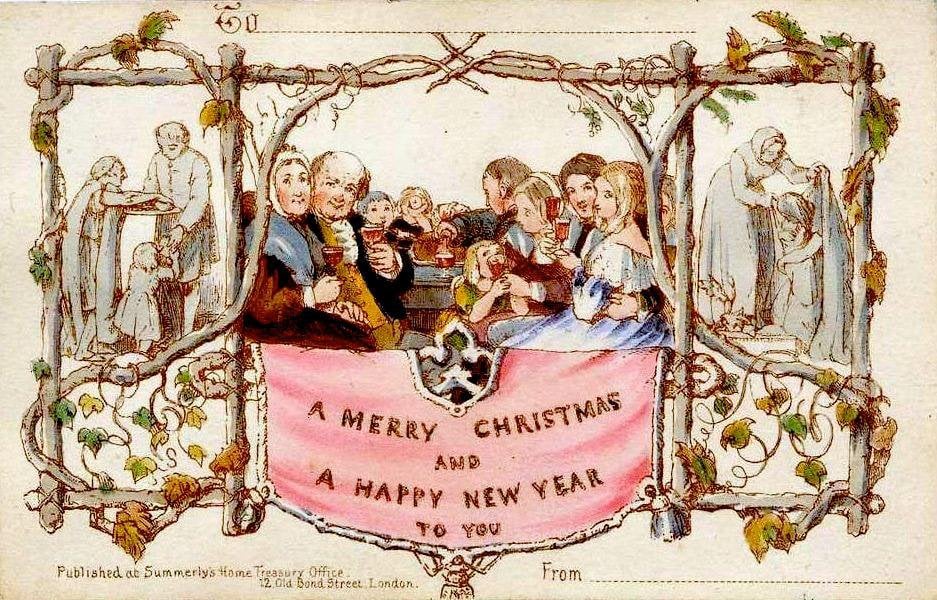

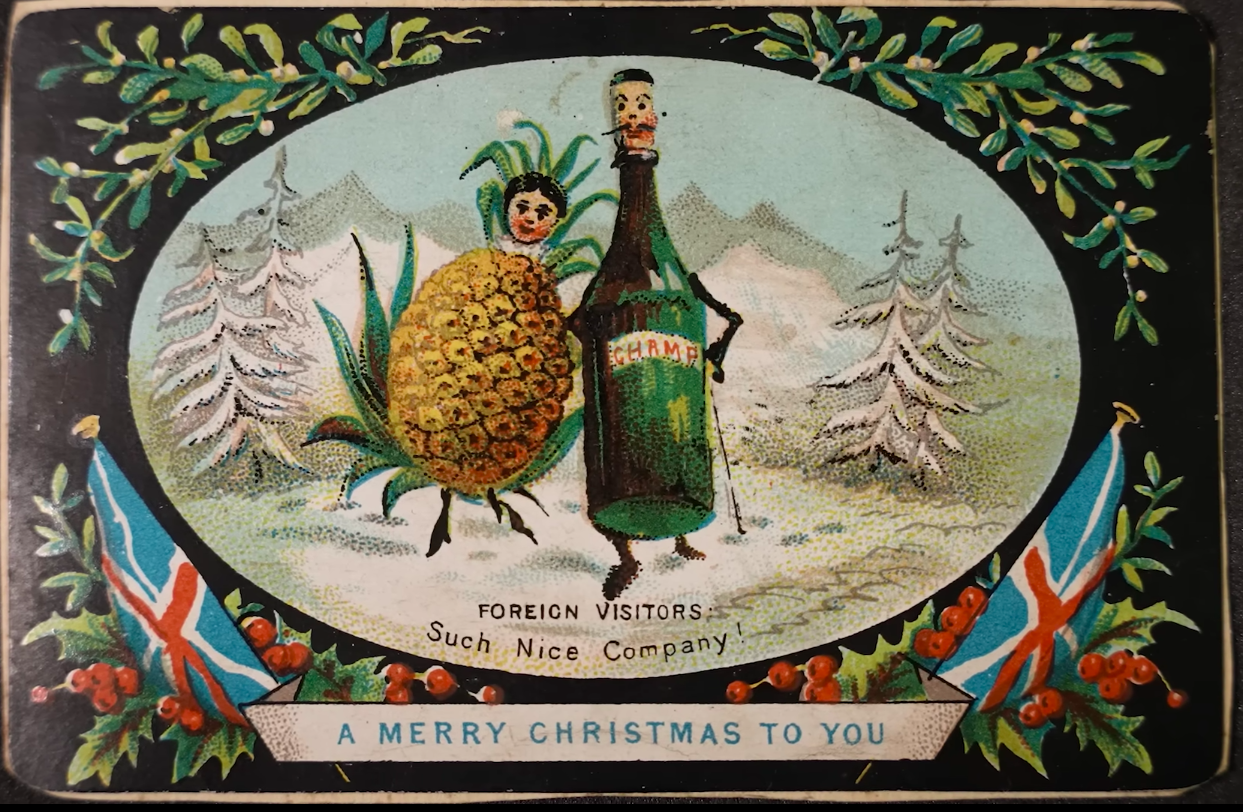

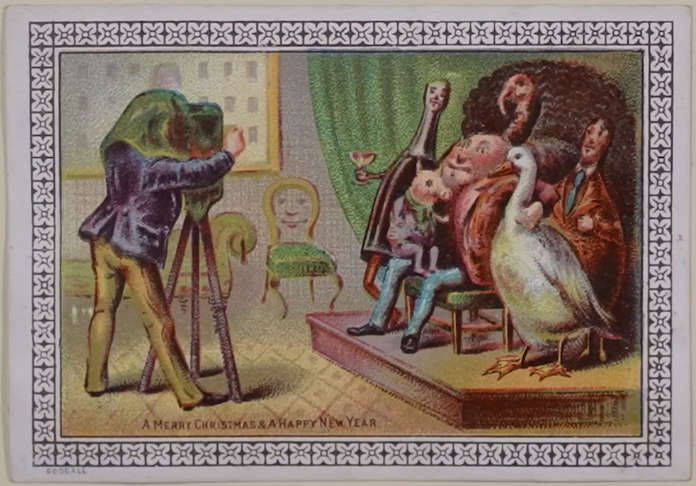

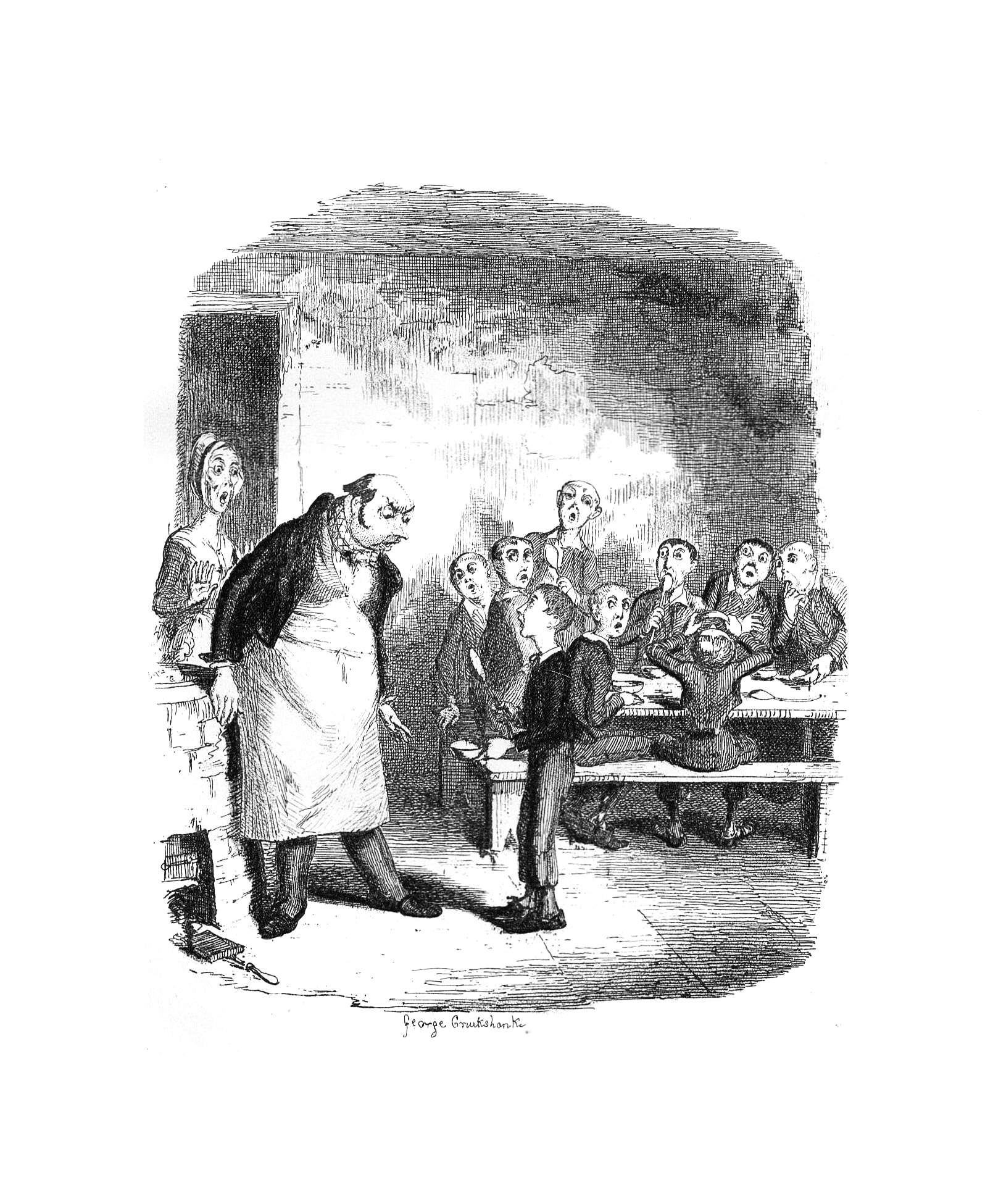

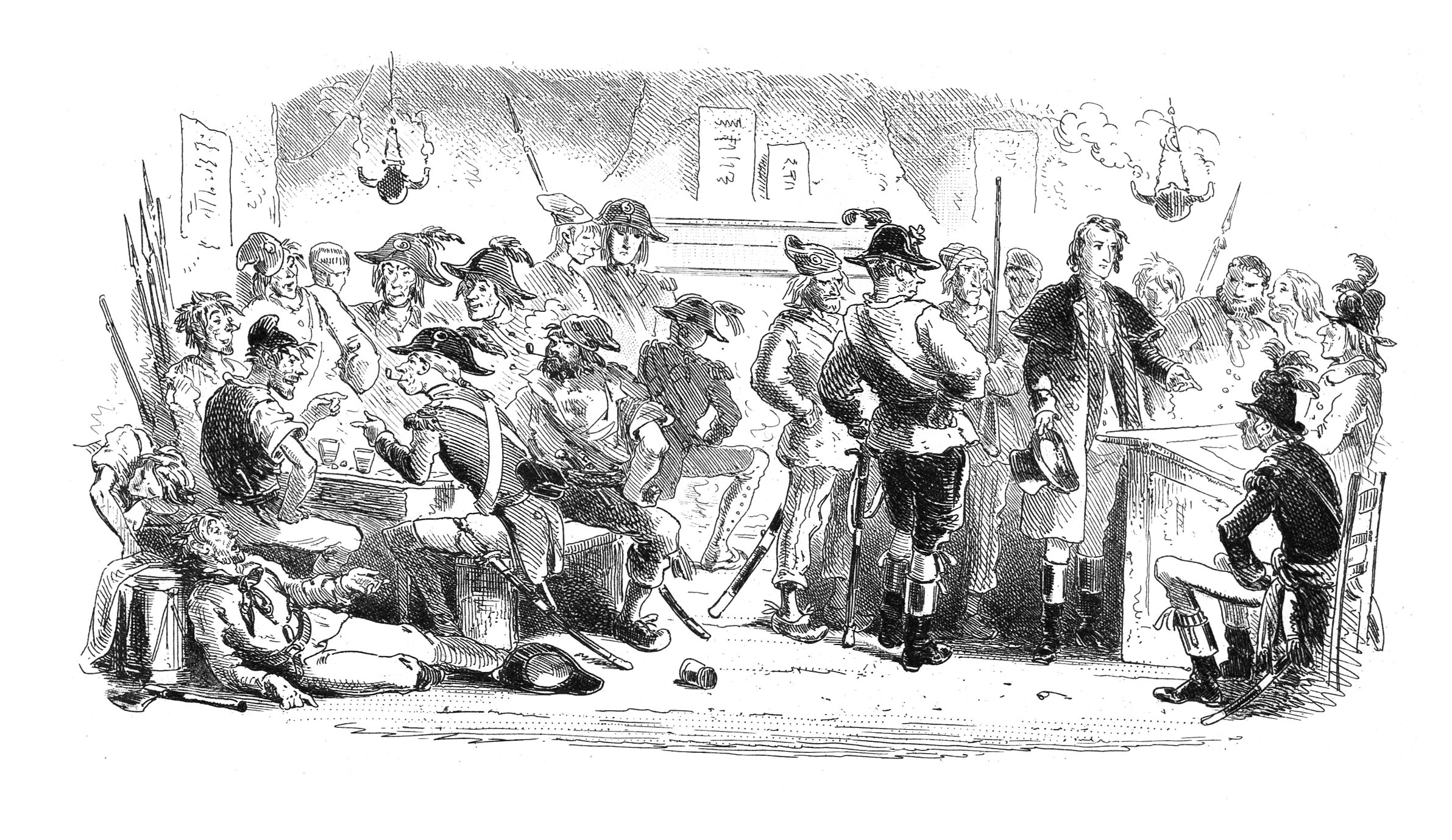

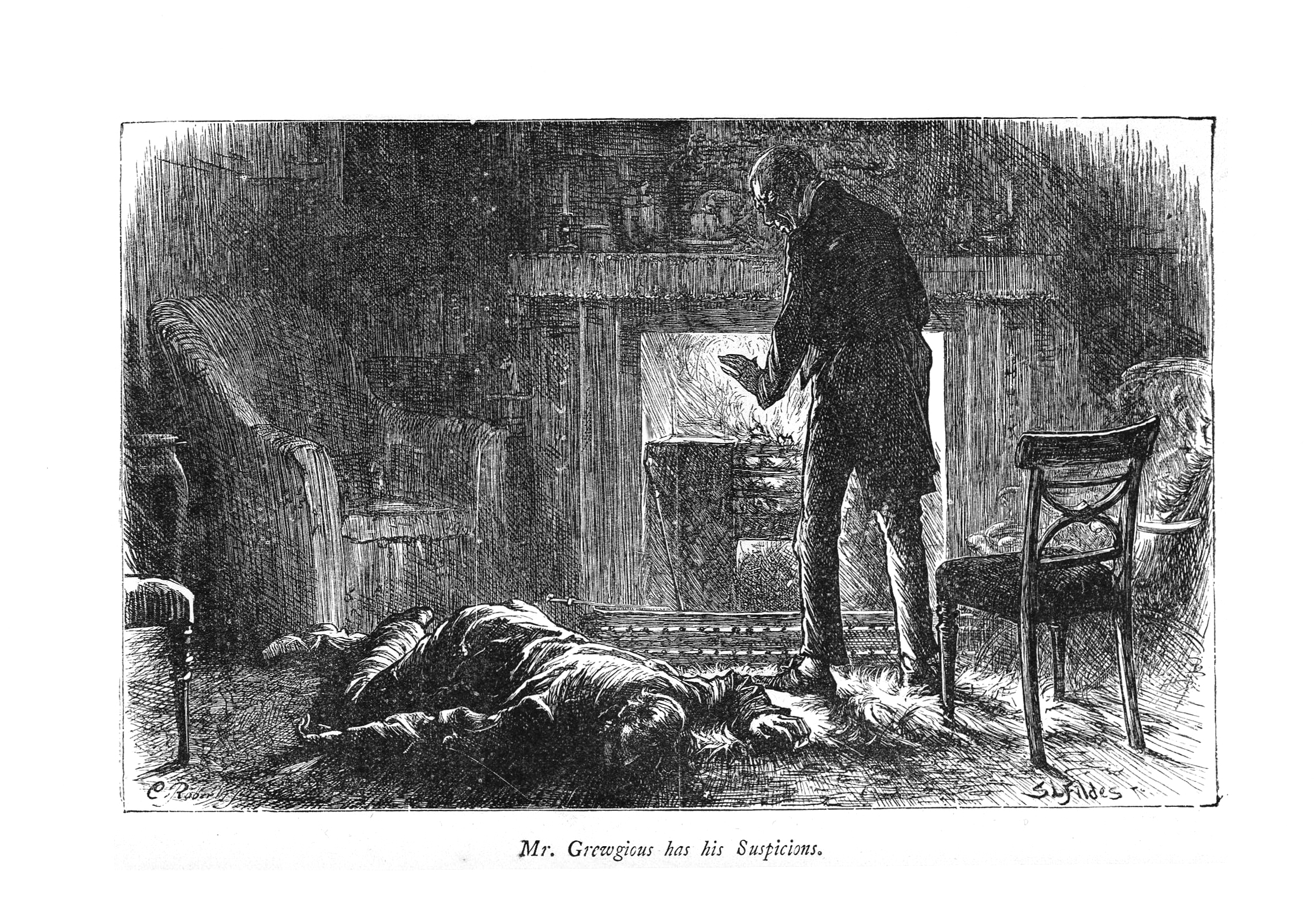

One such frontispiece appears at the top of this post, depicting the first appearance of The Pickwick Papers’ most beloved character, the cockney valet Samuel Weller (who overtook the title character in popularity in much the same manner as Dickens’ writing overtook the illustrations). The Charles Dickens Illustrated Gallery contains numerous plates from that book, as well as from all the rest: Oliver Twist (a collaboration with not Phiz but George Cruikshank), A Christmas Carol (with John Leech), Bleak House (its grim atmosphere heightened by Phiz’s “dark plates”), even the never-finished The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Today’s readers are likely to dismiss these illustrations, however well-rendered, as extraneous to the text. But we must bear in mind that most were seen and approved by Dickens himself, who knew what he wanted — and even more so, what his readers wanted.

Enter the The Charles Dickens Illustrated Gallery here.

Related content:

An Animated Introduction to Charles Dickens’ Life & Literary Works

An Oscar-Winning Animation of Charles Dickens’ Classic Tale, A Christmas Carol (1971)

Behold Illustrations of Every Shakespeare Play Created by Artificial Intelligence

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.