Are you one of the hundreds of thousands who’ve gotten themselves hooked on Wordle, the free online game that gives players six chances to guess a five-letter word of the day?

Its popularity has spawned a host of imitators, including Quordle, Crosswordle, Absurdle and Lewdle, which has carved itself a niche in the vulgar and profane.

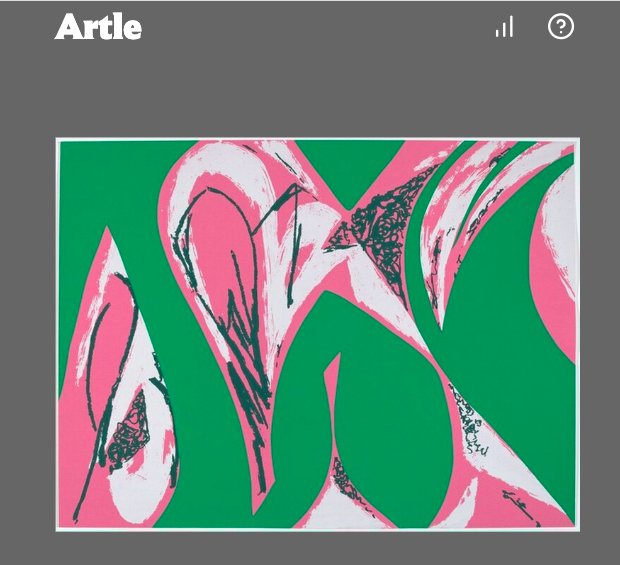

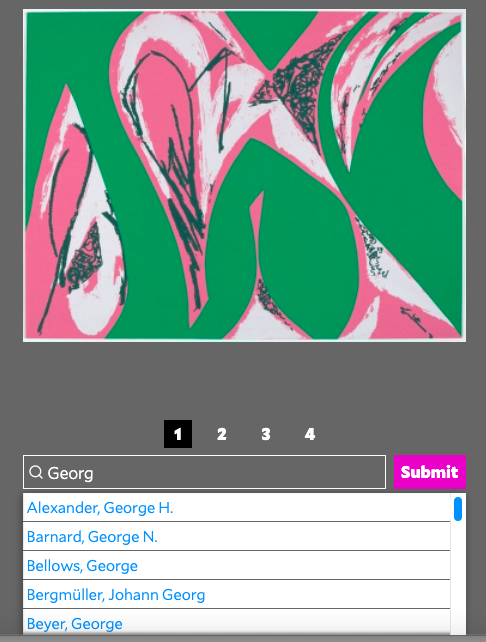

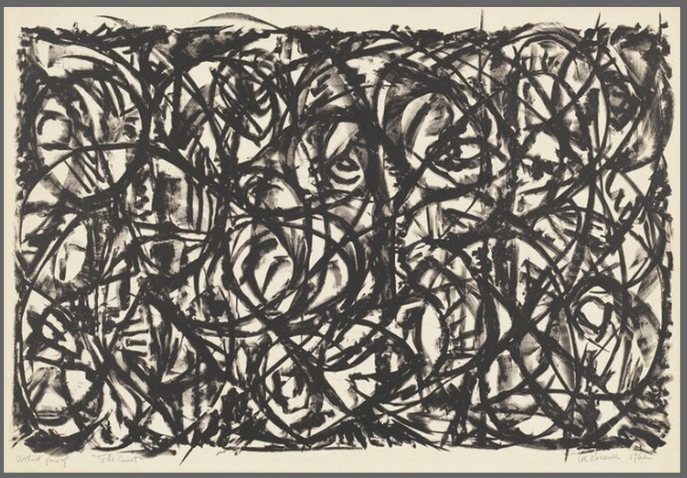

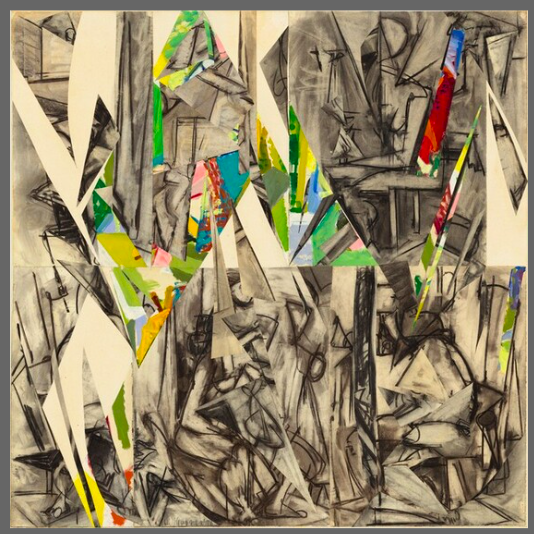

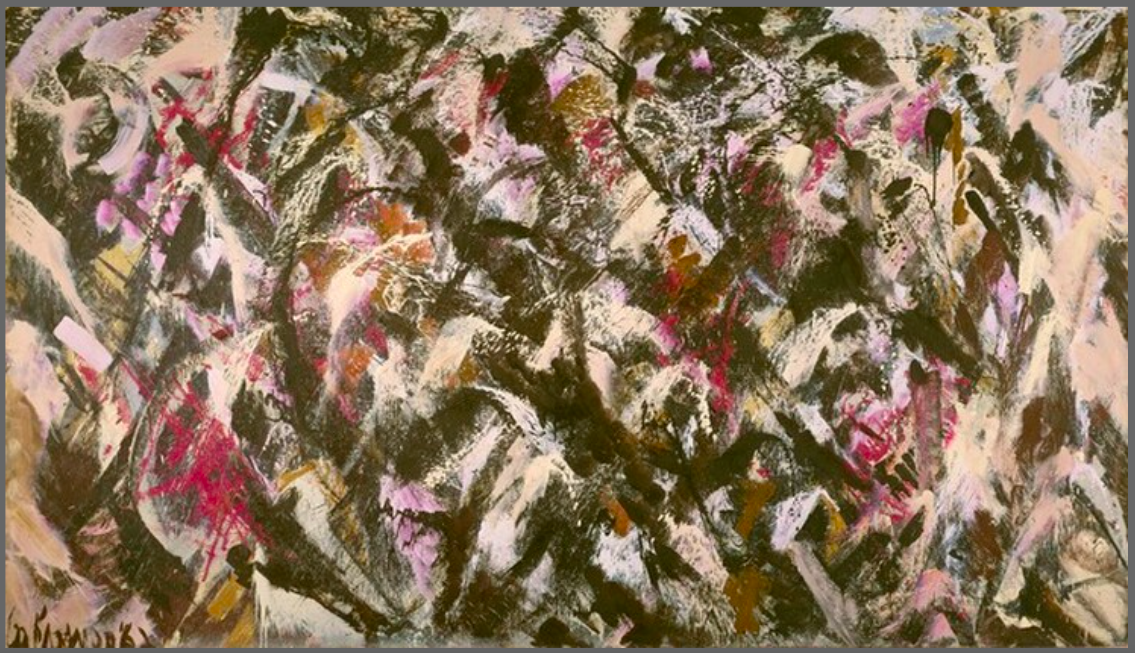

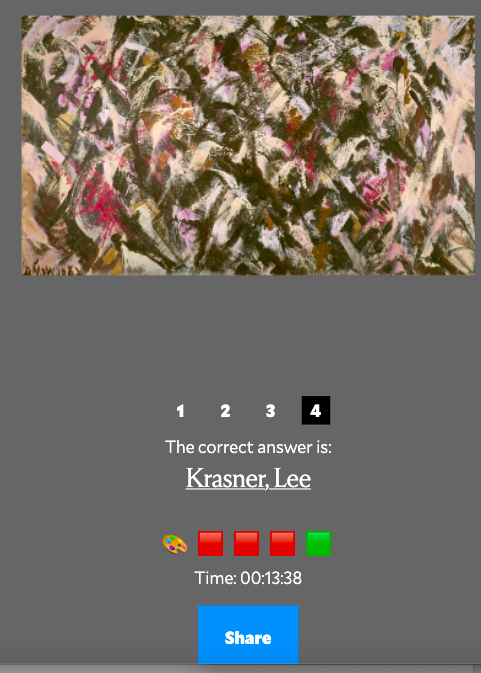

Even the National Gallery of Art is getting in on the action with Artle, wherein players get four attempts to correctly identify an artist du jour by examining four of their pieces, drawn from its vast collection of paintings, photographs, sculptures and other works.

The Gallery provides a bit of an assist a few letters into every guess, especially helpful to those taking wild shots in the dark.

Before you commit to Georgia O’Keeffe, you may want to consider some 80 other George and Georges variants who pop up as you type, including Georges Braque, George Grosz, Georgine E. Mason, George Joji Miyasaki, George Segal, Georges Seurat, and Georg Andreas Wolfgang the Elder.

Hats off if you can readily identify all of these artists’ work on sight. That’s an impressive command of art history you’ve got there!

As with Wordle, a button provides a streamlined invitation to boast about your prowess on social media after you’ve completed your daily Artle. Return visitors can keep track of their stats in the upper right hand corner.

There’s no shame in failing to identify an artist in four tries, just a free opportunity to further your education a bit with titles and links to the four works you just spent time viewing.

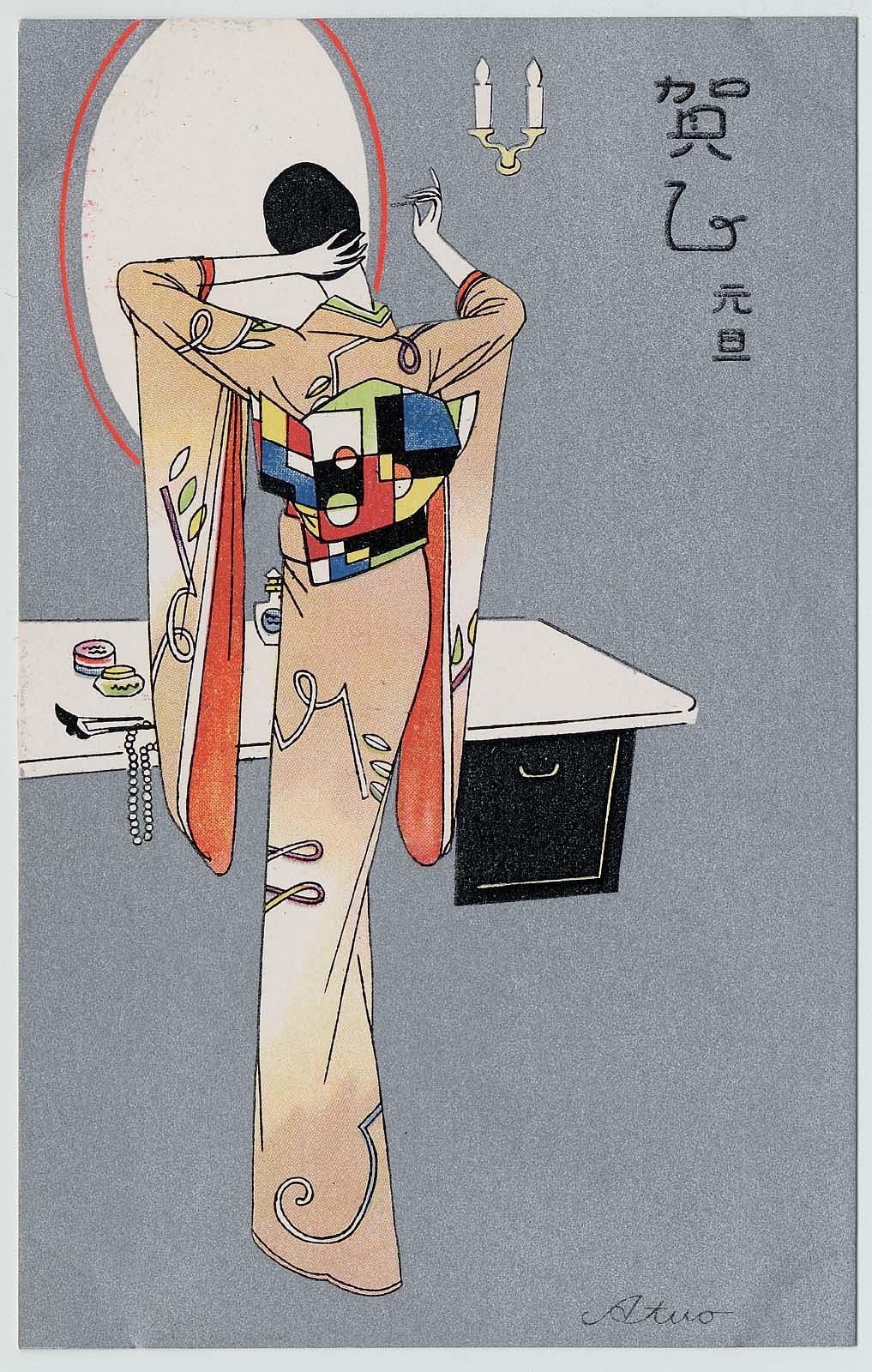

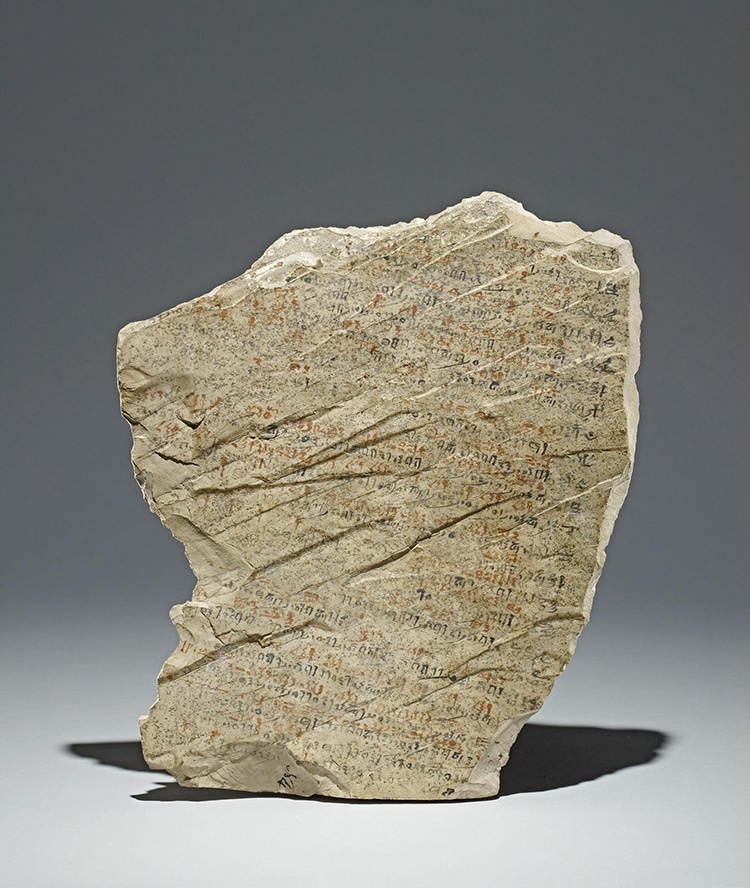

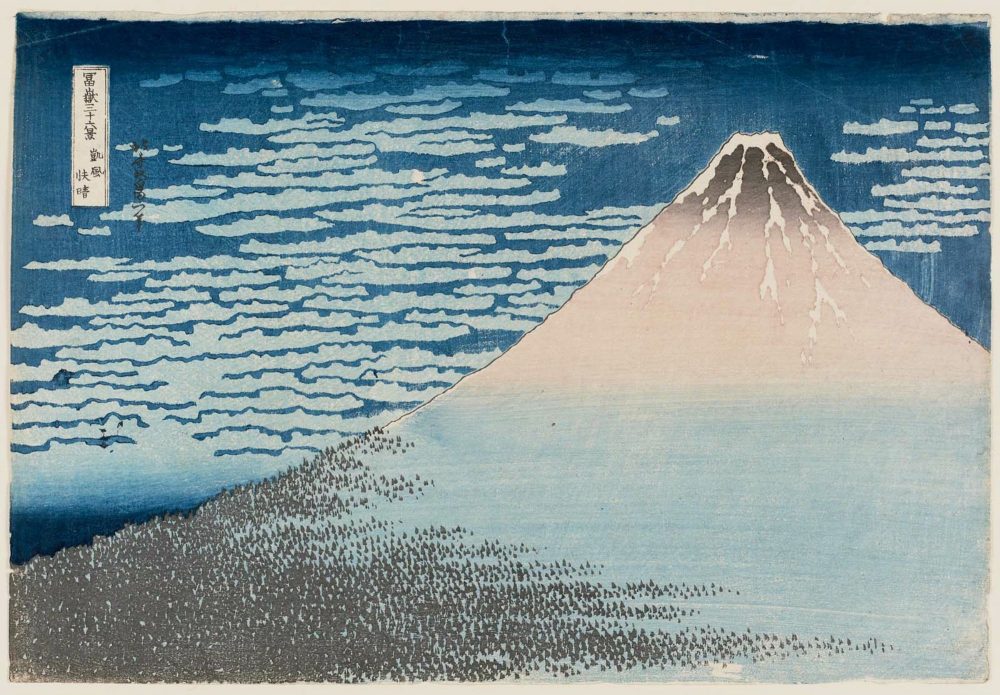

The examples we’ve included from Thursday, June 2’s puzzle are Free Space (Deluxe), pink, The Civet, Imperative, and Cobalt Night by….

Your guess?

Play Artle here — like Wordle and multivitamins, just one a day.

Related Content

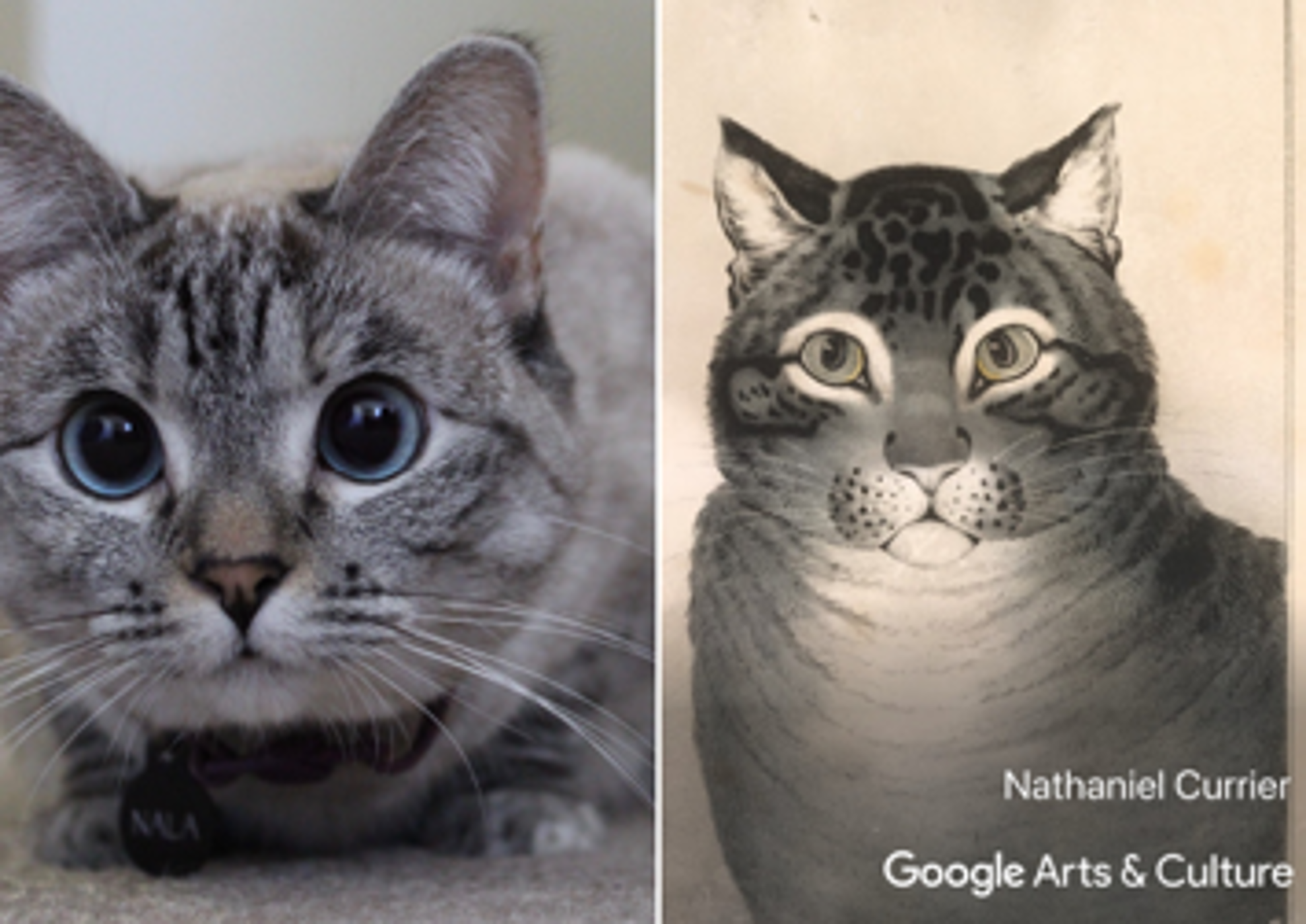

Google’s Free App Analyzes Your Selfie and Then Finds Your Doppelganger in Museum Portraits

Construct Your Own Bayeux Tapestry with This Free Online App

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.