With the exception of Kara Walker’s provocative cut paper narratives, silhouettes haven’t struck us as a particularly revealing art form.

Perhaps we would have felt differently in the early 19th-century, when silhouettes offered a quick and affordable alternative to oil portraits, and photography had yet to be invented.

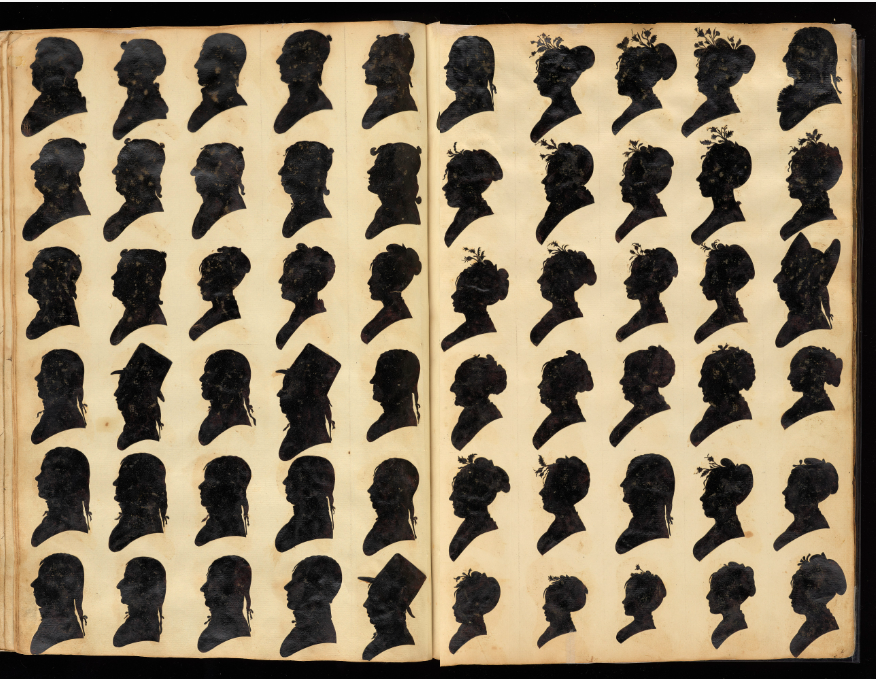

Self-taught silhouette artist William Bache traveled the eastern seaboard, and later to New Orleans and Cuba, plying his trade with a physiognotrace, a device that helped him outline subjects’ profiles on folded sheets of light paper.

Once a profile had been captured, Bache carefully cut inside the tracing and affixed the “hollow-cut” surrounding sheet to black paper, creating the appearance of a hand-cut black silhouette on a white background.

Customers could purchase four copies of these shadow likenesses for 25¢, which, adjusted for inflation, is about the same amount as a photo strip in one of New York City’s vintage photobooths these days — $5.

Bache was an energetic promoter of his services, advertising that if customers found it inconvenient to visit one of his pop-up studios, he would “at the shortest notice, wait upon them at their own Dwellings without any additional expense.”

Naturally, people were eager to lay hands on silhouettes of their children and sweethearts, too.

One of Bache’s competitors, Raphaelle Peale assumed the perspective of a satisfied male customer to tout his own business:

‘Tis almost herself, Eliza’s shade,

Thus by the faithful facietrace pourtray’d!

Her placid brow and pouting lips, whose swell

My fond impatient ardor would repell.

Let me then take that vacant seat, and there

Inhale her breath, scarce mingled with the air:

And thou blest instrument! which o’er her face

Did’st at her lips one moment pause, retrace

My glowing form and leave, unequall’d bliss!

Borrow’d from her, a sweet etherial Kiss.

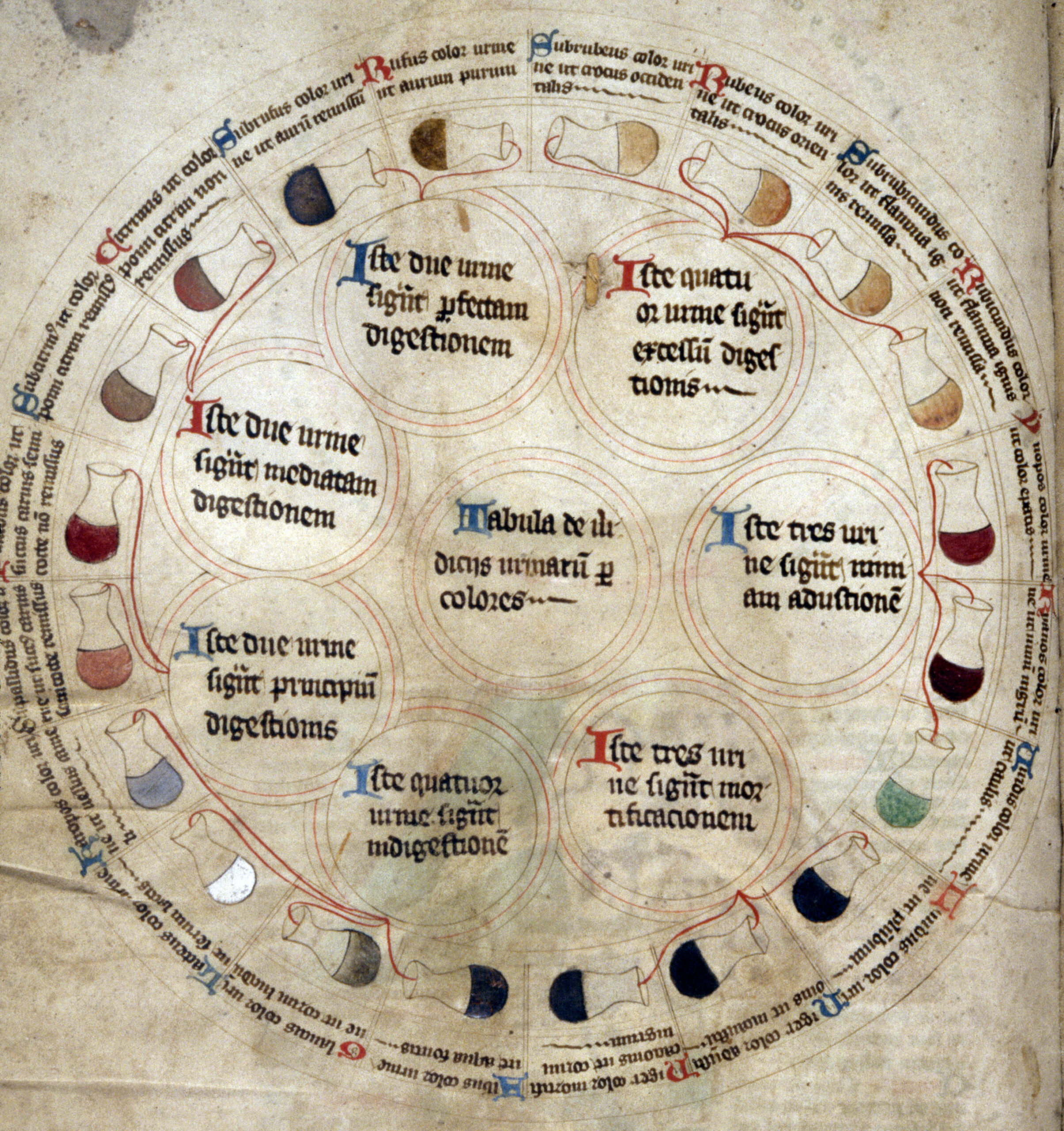

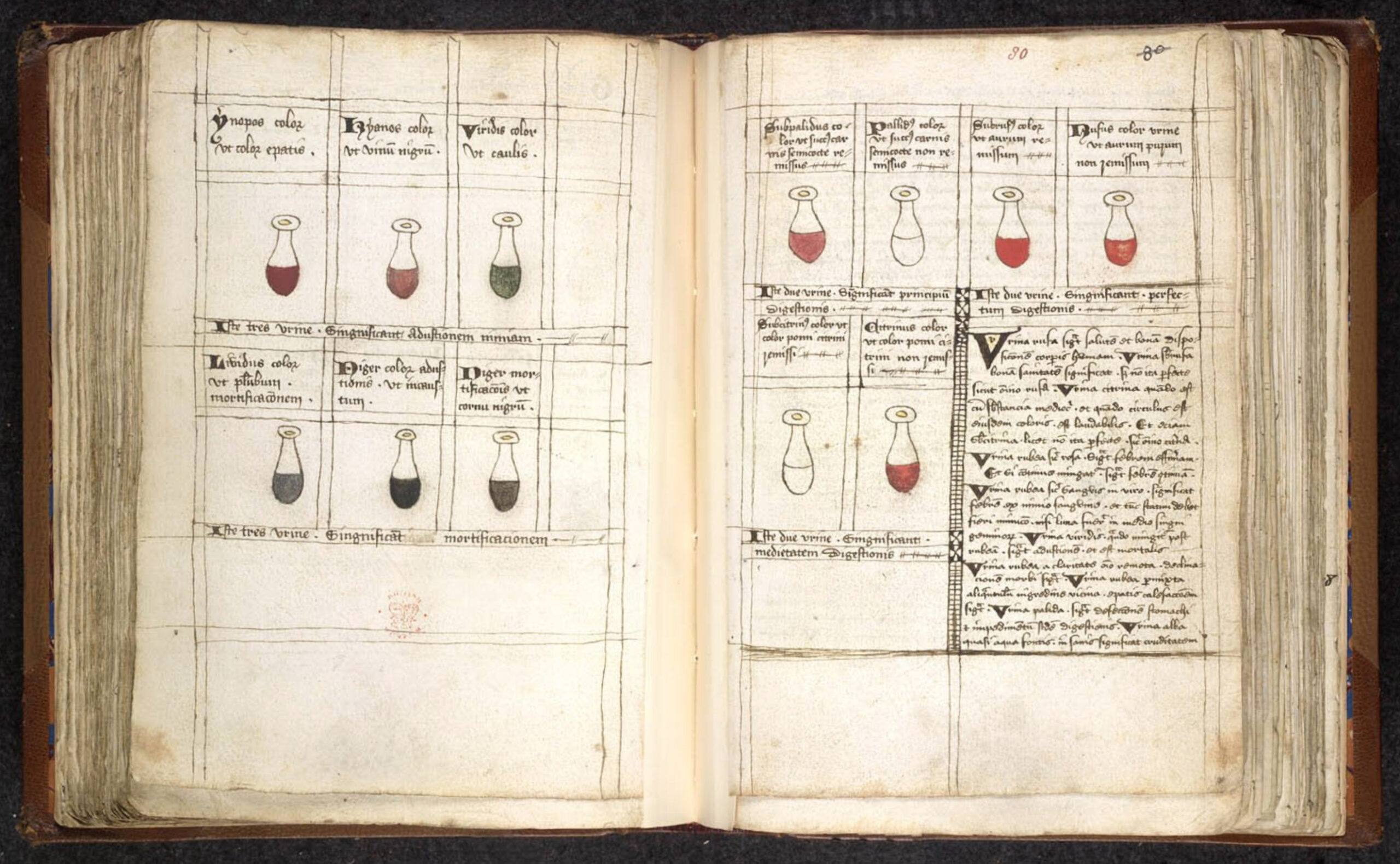

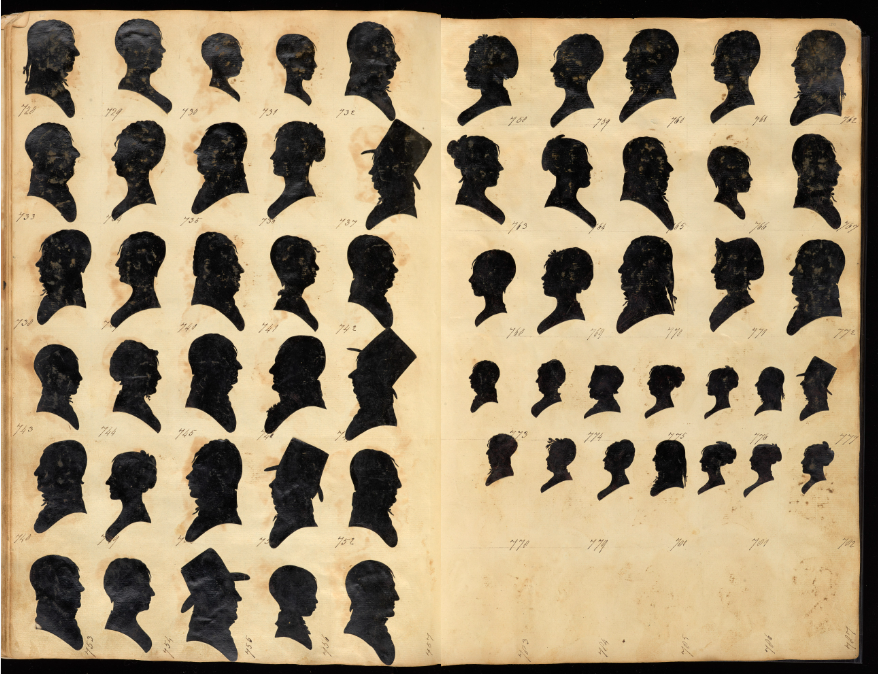

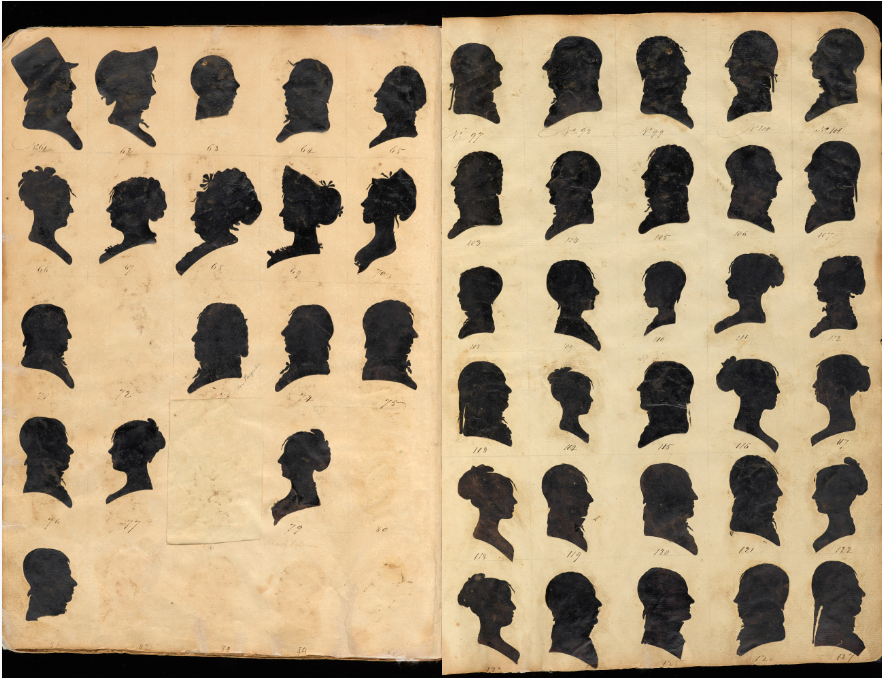

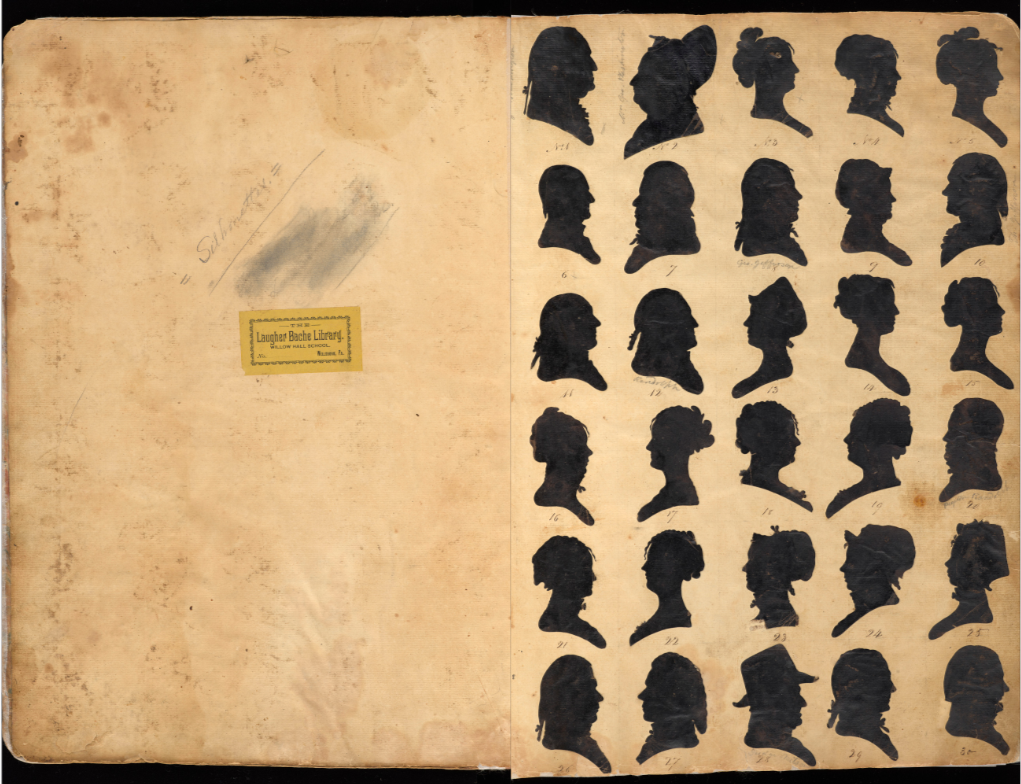

Hot stuff, though hopefully besotted young lovers refrained from pressing their lips to the silhouettes they loved best. Conservators in the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, which houses Bache’s sample book, a ledger filled with likenesses of some 1,800 sitters, discovered it to be suffused with arsenic, presumably meant to repel invading rodents and insects.

Most of the heads in Bache’s album arrived unidentified, but by combing through digitized newspapers, history books, baptismal records, wills, marriage certificates and Ancestry.com, lead curator Robyn Asleson and Getty-funded research assistant Elizabeth Isaacson have managed to identify over 1000.

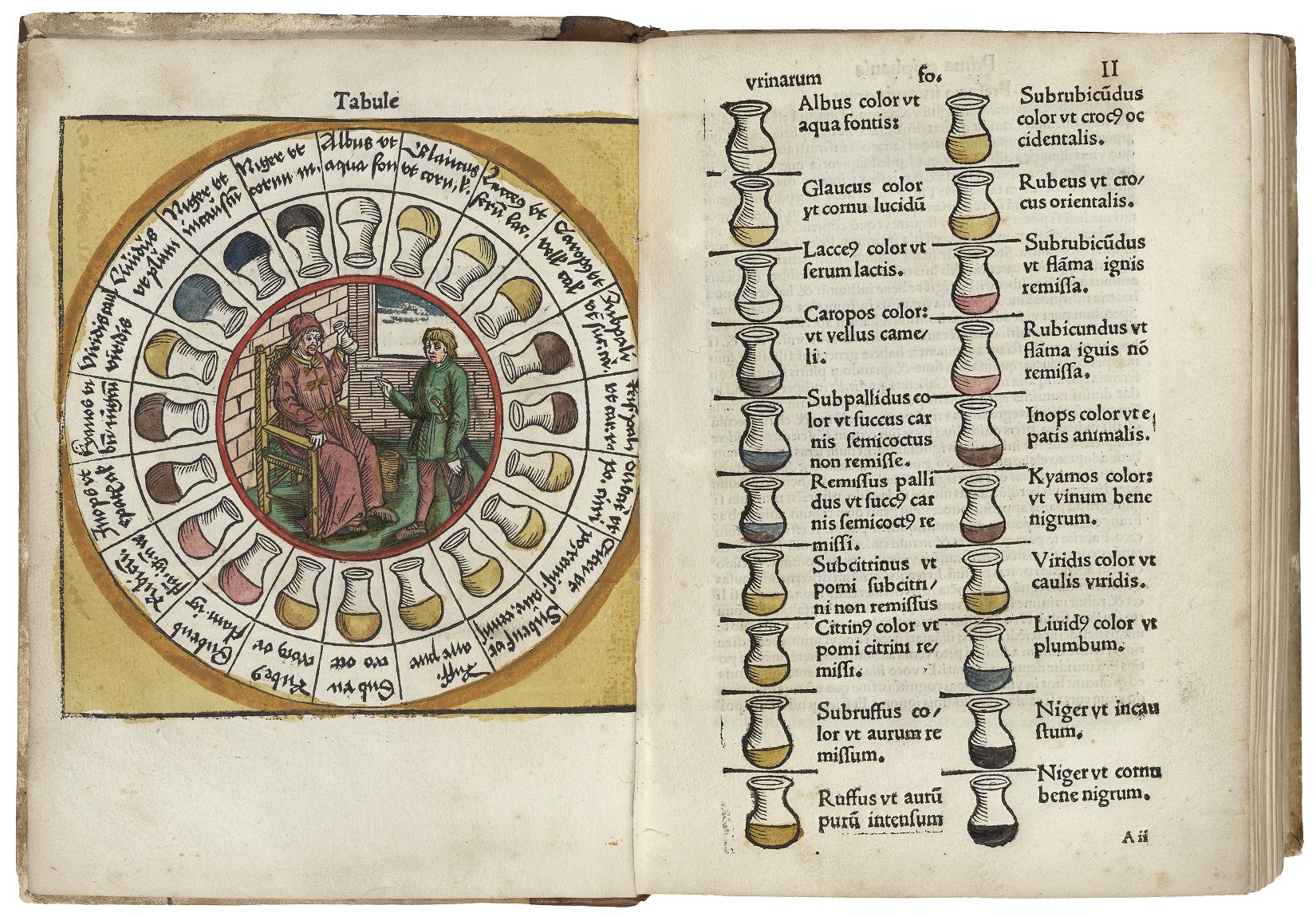

There are some whose names — and profiles — remain well known more than 200 years later. Can you identify George Washington, Martha Washington, and Thomas Jefferson on the album page below?

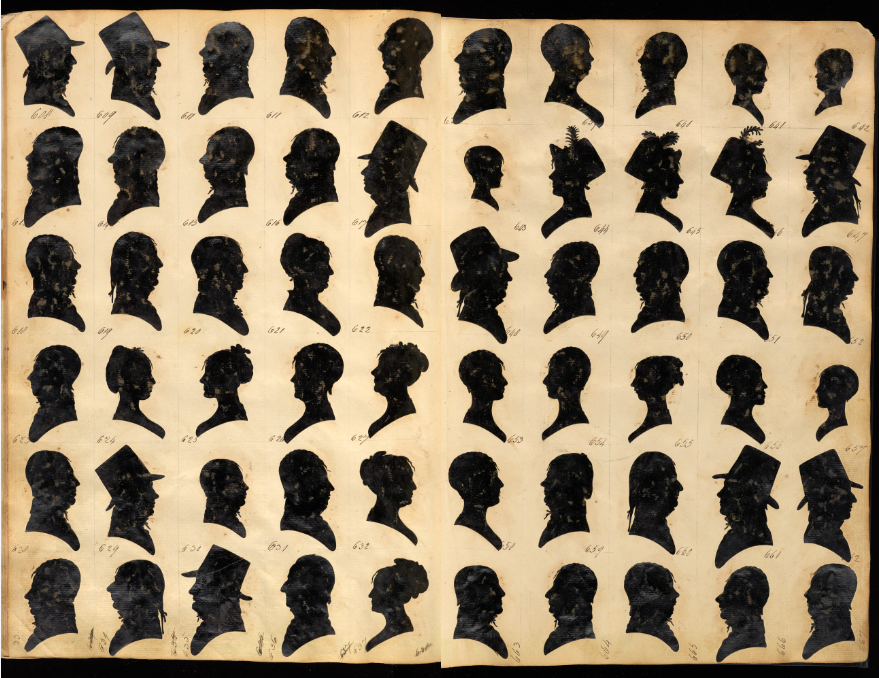

Some pages contain entire families. Pedro Bidetrenoulleau coughed up $1.25 for his own likeness, as well as those of his wife, and children Félix, Adele, and Zacharine, numbers 638 through 642, below.

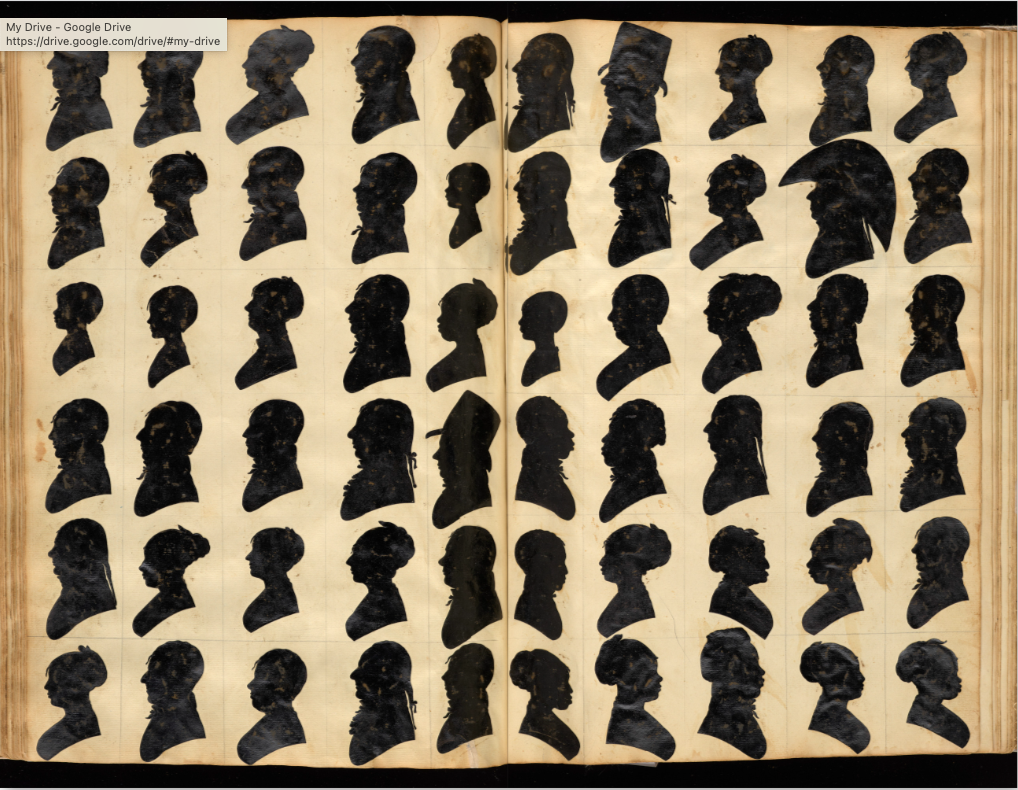

Bache’s travels to New Orleans and Cuba make for a racially diverse collection, though little is known about most of the Black sitters. Dr. Asleson suspects some of these might be the only existing portraits of these individuals, particularly in the case of New Orleanians in mixed-race relationships, whose descendants destroyed strategic evidence in the effort to “pass” as white:

As I was learning more and more about this history, I really began to hope that some of the people who are trying to find their heritage today, who realize it might have been deliberately eradicated to protect their ancestors from oppression, might have the chance to discover an image of a great-great-grandfather or grandmother.

Readers, if you are the caretaker of passed down family silhouettes, perhaps you can help the curators get closer to putting a name to someone who currently exists as little more than a shadow in interesting headgear.

Even if you’re not in possession of a silhouette, you may well be one of the tens of thousands living in the United States today connected to the album by blood.

Explore an arsenic-free, interactive copy of William Bache’s silhouette ledger book here.

Related Content

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.