The tarot goes back to Italy of the late Middle Ages. Every day here in the 21st century, I see undeniable signs of its cultural and temporal transcendence: specifically, the tarot shops doing business here and there along the streets of Seoul, where I live. The tarot began as a deck for play, but these aren’t dealers in card-gaming supplies; rather, their proprietors use tarot decks to provide customers suggestions about their destiny and advice on what to do in the future. Over the past five or six centuries, the purpose of the tarot many have changed, but its original artistic sensibility — dramatic, symbol-laden, and highly subject to counterintuitive interpretation — has remained intact.

You can get an idea of that original artistic sensibility by taking a look at the the Sola-Busca, the oldest known complete deck of tarot cards. Dating from the 1490s, it holds obvious historical interest, but it’s hardly the only tarot deck we’ve featured here on Open Culture.

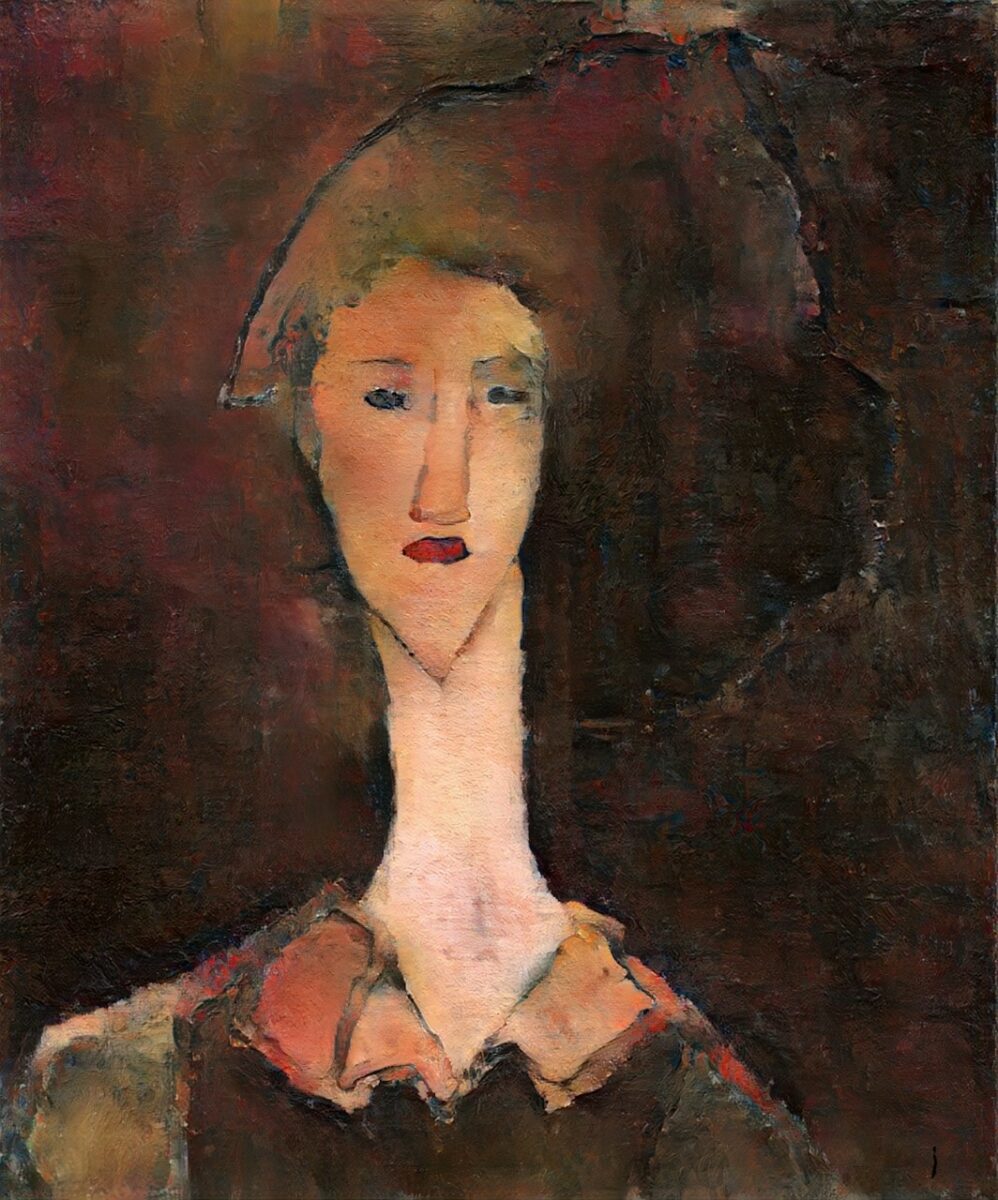

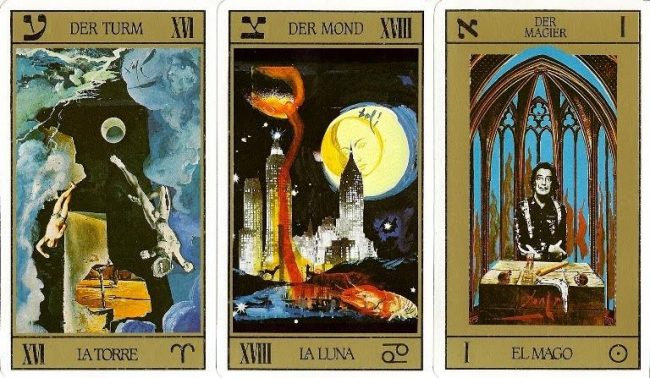

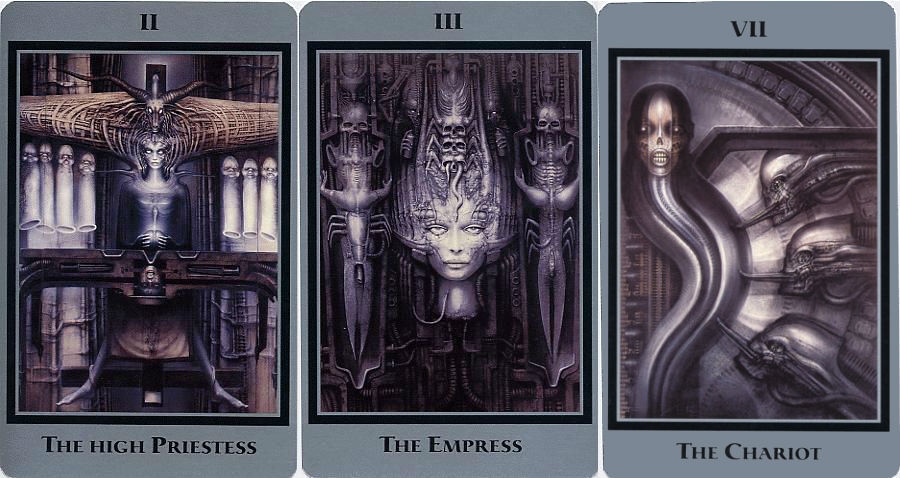

Artists of subsequent eras, up to and including our own, have created special decks in accordance with their distinctive visions. The unstoppable surrealist Salvador Dalí designed his own, a project embarked upon at the behest of James Bond film producer Albert Broccoli. Later, the master of biomechanism H.R. Giger received a tarot commission as well; though his deck uses previously unpublished rather than custom-made art, it all looks surprisingly, sometimes chillingly fitting.

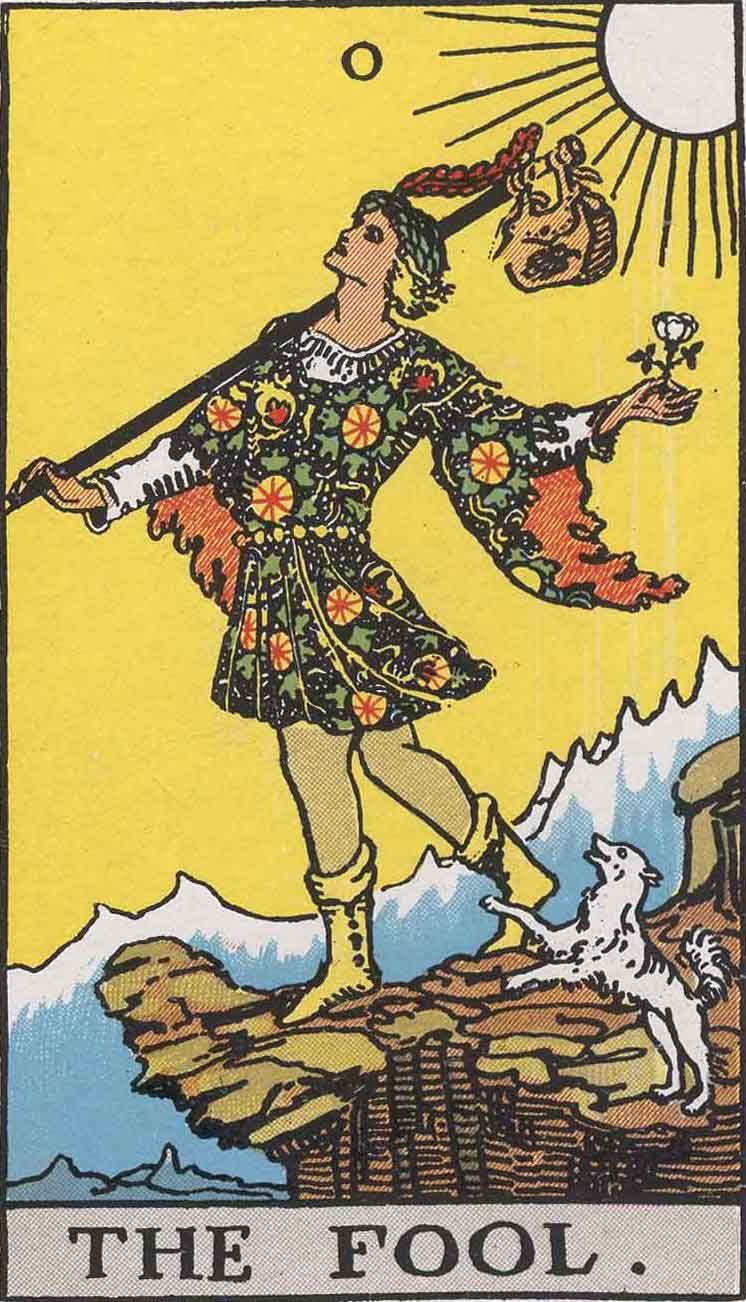

The world’s most popular tarot deck was designed not by a famous artist, but by an illustrator named Pamela Coleman-Smith. Many more have used and appreciated her work than even, say, the Thoth deck, designed by no less renowned an occultist than Aleister Crowley, “the wickedest man in the world.” If you won’t take his word for it, perhaps the founder of analytical psychology can sell you on the merits of tarot: for Carl Jung, the deck held out the possibility of the “intuitive method” he sought for “understanding the flow of life, possibly even predicting future events, at all events lending itself to the reading of the conditions of the present moment.” (See his deck here.) Even if you’re not in search of such a method, few other artifacts weave together so many threads of art, philosophy, history, and symbolism. Of course, no few modern enthusiasts find in it the same appeal as did those early tarot players of the 15th century: it’s fun.

Related Content:

Meet the Forgotten Female Artist Behind the World’s Most Popular Tarot Deck (1909)

The Thoth Tarot Deck Designed by Famed Occultist Aleister Crowley

Behold the Sola-Busca Tarot Deck, the Earliest Complete Set of Tarot Cards (1490)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.