At the moment, there’s no better way to see anything in space than through the lens of the James Webb Space Telescope. Previously featured here on Open Culture, that ten-billion-dollar successor to the Hubble Space Telescope can see unprecedentedly far out into space, which, in effect, means it can see unprecedentedly far back in time: some 13.5 billion years, in fact, to the state of the early universe. We posted the first photos taken by the James Webb Space Telescope in 2022, which showed us distant galaxies and nebulae at a level of detail in which they’d never been seen before.

Such images would scarcely have been imaginable to James Nasmyth, though he might have foreseen that they would one day be a reality. A man of many interests, he seems to have pursued them all during the nineteenth century through which he lived in its near-entirety.

His invention of the steam hammer, which turned out to be a great boon to the shipbuilding industry, did its part to make possible his early retirement. At that point, he was freed to pursue such passions as astronomy and photography, and in 1874, he published with co-author James Carpenter a book that occupied the intersection of those fields.

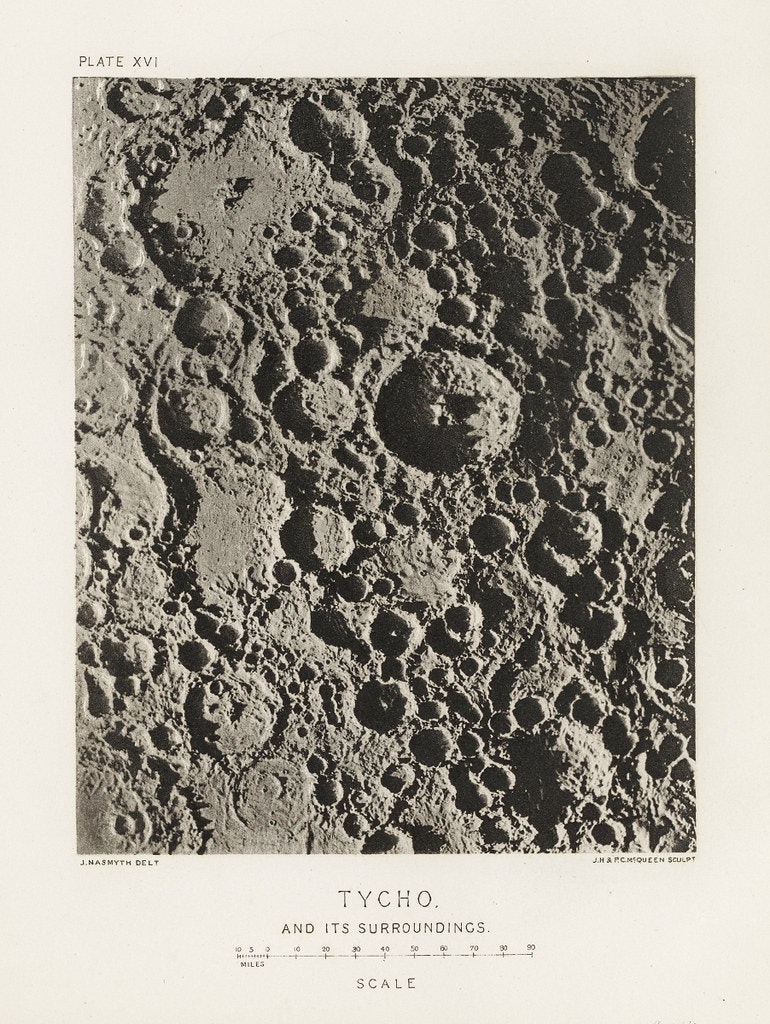

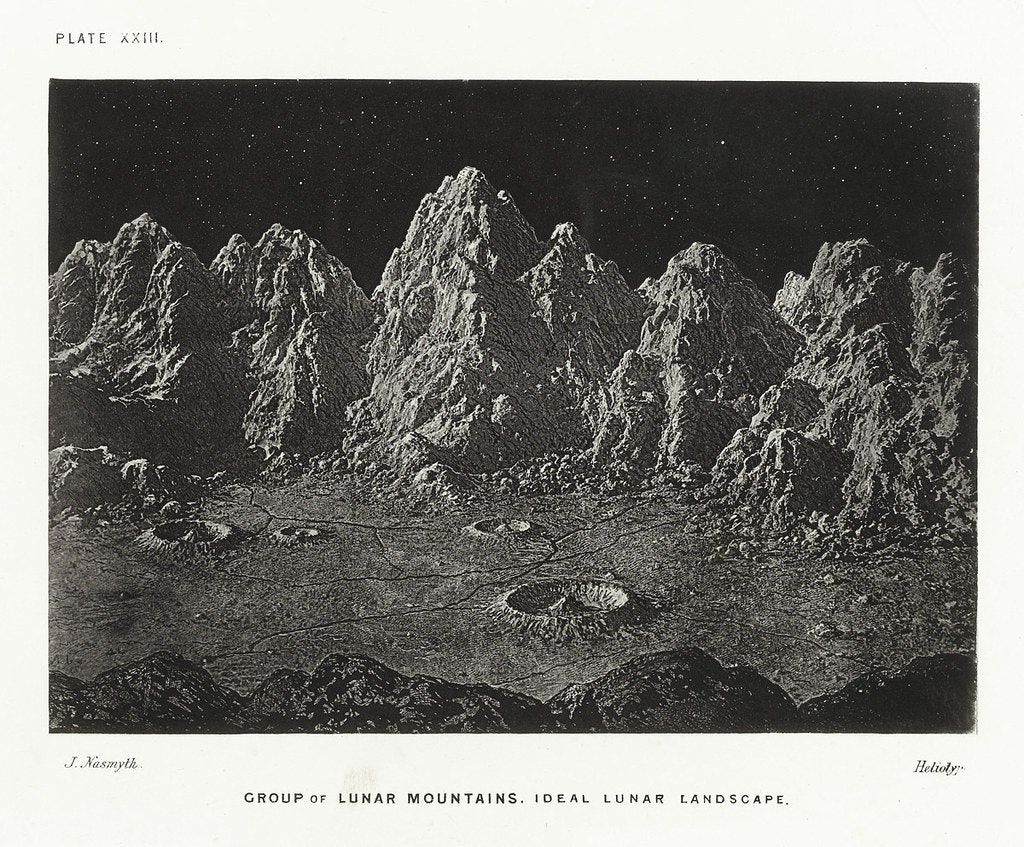

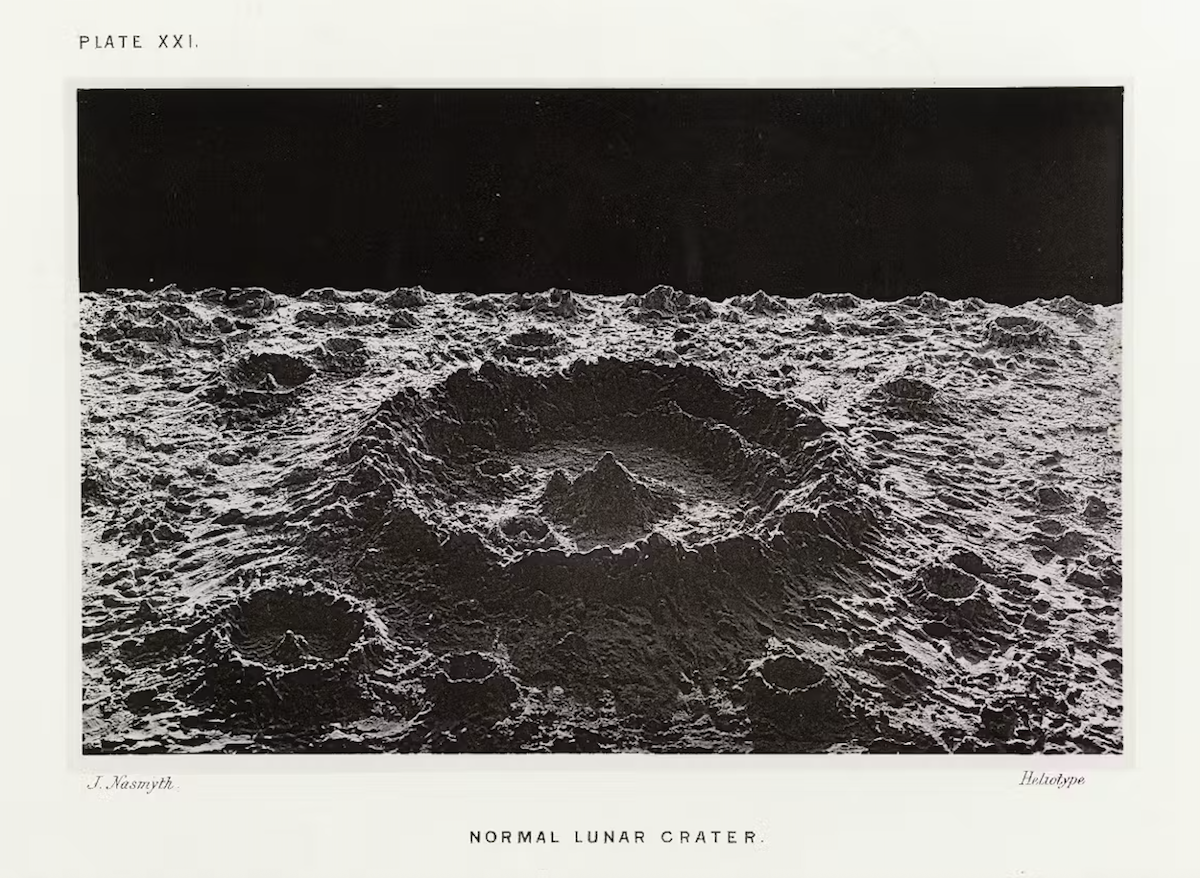

The Moon: Considered as a Planet, a World, and a Satellite contains what still look like strikingly detailed photos of the surface of that familiar but then-still-mysterious heavenly body: quite a coup at the time, considering that the technology for taking pictures through a telescope had yet to be invented. Nasmyth did use a telescope — one he made himself — but only as a reference in order to sketch “the moon’s scarred, cratered and mountainous surface,” writes Ned Pennant-Rea at the Public Domain Review. “He then built plaster models based on the drawings, and photographed these against black backgrounds in the full glare of the sun.”

In the book’s text, Nasmyth and Carpenter showed a certain scientific prescience with their observations on such phenomena as the “stupendous reservoir of power that the tidal waters constitute.” You can read the first edition at the Internet Archive, and you can see more of its photographs at the Public Domain Review. Compare them to pictures of the actual moon, and you’ll notice that he got a good deal right about the look of its surface, especially given the tools he had to work with at the time. There’s even a sense in which Nasmyth’s photos look more real than the 100 percent faithful images we have now, that they vividly represent something of the moon’s essence. As millions of disappointed viewers of CGI-saturated modern sci-fi movies understand, sometimes only models feel right.

Related content:

The First Surviving Photograph of the Moon (1840)

The Very First Picture of the Far Side of the Moon, Taken 60 Years Ago

The Full Rotation of the Moon: A Beautiful, High Resolution Time Lapse Film

The Evolution of the Moon: 4.5 Billions Years in 2.6 Minutes

A Trip to the Moon (1902): The First Great Sci-Fi Film

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.