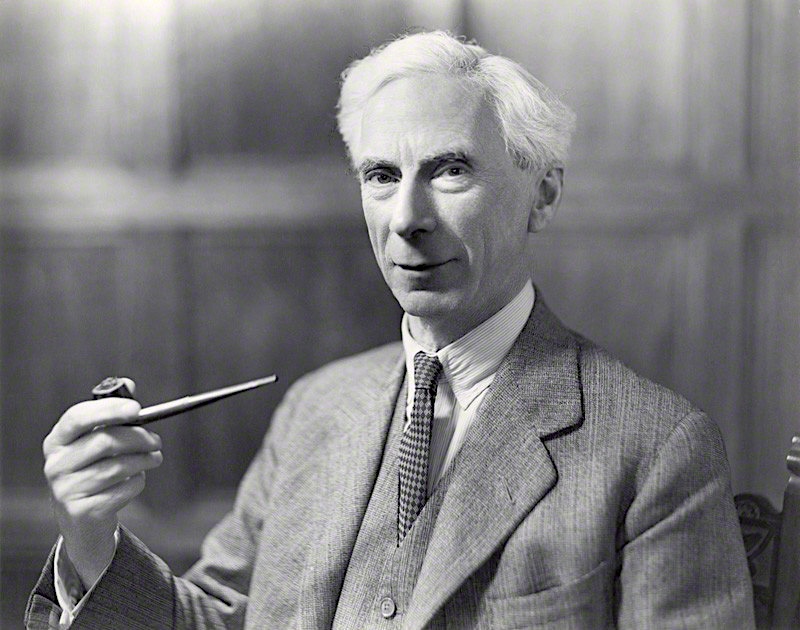

Image by Walter Crist

As far as enthusiasm for board games goes, no continent has yet outdone Europe. Its advantage could lie in the highly developed culture of low-cost leisure evident in quite a few of its societies; it could also owe to the fact that board games seem to have been played there continuously since antiquity. We’ve long had evidence of examples like the “Roman mill game,” better known today as nine men’s morris, which Ovid appears to mention in his Ars Amatoria of the very early first century. Not that modern knowledge of Roman tabletop gaming is complete. In one puzzling case, the stone board above was unearthed in a former Roman town in the Netherlands, but how a game was played on it remained a mystery — until machine learning came along.

“To examine whether the object may have been used as a game board, we performed use-wear analysis to identify evidence for gameplay and we simulated play using artificial intelligence (AI),” write the team of researchers who recently published a paper on the subject in the journal Antiquity. They used a system called Ludii, engineered to analyze board-game rules.

“This software allows for AI-driven playout simulation, where two AI agents play a game against one another, which can generate quantitative data on gameplay. In this instance, we explored whether the rules of a game would produce the wear pattern seen on the stone.” The idea, in other words, was to let the computer play against itself using different rules until it came upon a game that would continue to abrade away the surface of the board in the same fashion as it already was.

This process narrowed it down to games “in which the goal is to block the opponent from moving, and those in which the goal is to place three pieces in a row.” These have a fairly long documented history, from Scandinavia’s haretavl, to Italy’s gioco dell’orso to Spain’s liebre perseguida, to Greece’s kinégi tou lagoú. You can download what the research suggests is the most plausible rule set for this particular Roman board game here, board design included. One player takes the side of the “hunter,” with four pieces, and the other the side of the “prey,” with two. The former tries to trap the latter’s pieces, moving only along the board’s lines; in the next round, the roles reverse. The hunter who does the job in the fewest moves wins. Why not invite friends over to spend an evening playing like a Roman? For a thoroughly ancient good time, first reconstruct as best you can the ambience of the thermopolium at home.

Related content:

Behold the First American Board Game, Travellers’ Tour Through the United States (1822)

Monopoly: How the Original Game Was Made to Condemn Monopolies & the Abuses of Capitalism

Kurt Vonnegut’s Lost Board Game Is Finally for Sale

The Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas Board Game, Inspired by Hunter S. Thompson’s Rollicking Novel

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. He’s the author of the newsletter Books on Cities as well as the books 한국 요약 금지 (No Summarizing Korea) and Korean Newtro. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.