We credit the Bauhaus school, founded by German architect Walter Gropius in 1919, for the aesthetic principles that have guided so much modern design and architecture in the 20th and 21st centuries. The school’s relationships with artists like Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe mean that Bauhaus is closely associated with Expressionism and Dada in the visual and literary arts, and, of course, with the modernist industrial design and glass and steel architecture we associate with Frank Lloyd Wright and Charles and Ray Eames, among so many others.

We tend not to associate Bauhaus with the art of dance, perhaps because of the school’s founding ethos to bring what they saw as enervated fine arts and crafts traditions into the era of modern industrial production. The question of how to meet that demand when it came to perhaps one of the oldest of the performing arts might have puzzled many an artist.

But not Oskar Schlemmer. A polymath, like so many of the school’s avant-garde faculty, Schlemmer was a painter, sculptor, designer, and choreographer who, in 1923, was hired as Master of Form at the Bauhaus theatre workshop.

Before taking on that role, Schlemmer had already conceived, designed, and staged his most famous work, Das Triadische Ballett (The Triadic Ballet). “Schlemmer’s main theme,” says scholar and choreographer Debra McCall, “is always the abstract versus the figurative and his work is all about the conciliation of polarities—what he himself called the Apollonian and Dionysian. [He], like others, felt that mechanization and the abstract were two main themes of the day. But he did not want to reduce the dancers to automatons.” These concerns were shared by many modernists, who felt that the idiosyncrasies of the human could easily become subsumed in the seductive orderliness of machines.

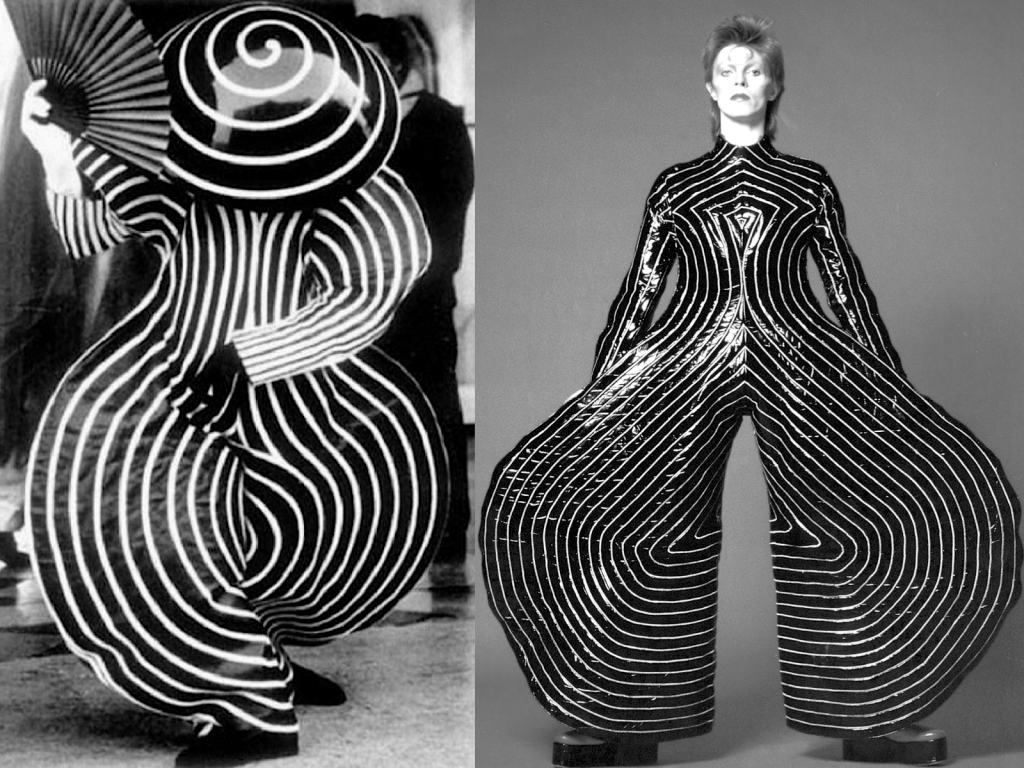

Schlemmer’s intentions for The Triadic Ballet translate—in the descriptions of Dangerous Minds’ Amber Frost—to “sets [that] are minimal, emphasizing perspective and clean lines. The choreography is limited by the bulky, sculptural, geometric costumes, the movement stiflingly deliberate, incredibly mechanical and mathy, with a rare hint at any fluid dance. The whole thing is daringly weird and strangely mesmerizing.” You can see black and white still images from the original 1922 production above (and see even more at Dangerous Minds). To view these bizarrely costumed figures in motion, watch the video at the top, a 1970 recreation in full, brilliant color.

For various reasons, The Triadic Ballet has rarely been restaged, though its influence on futuristic dance and costuming is considerable. The Triadic Ballet is “a pioneering example of multi-media theater,” wrote Jack Anderson in review of a 1985 New York production; Schlemmer “turned to choreography,” writes Anderson, “because of his concern for the relationships of figures in space.” Given that the guiding principle of the work is a geometric one, we do not see much movement we associate with traditional dance. Instead the ballet looks like pantomime or puppet show, with figures in awkward costumes tracing various shapes around the stage and each other.

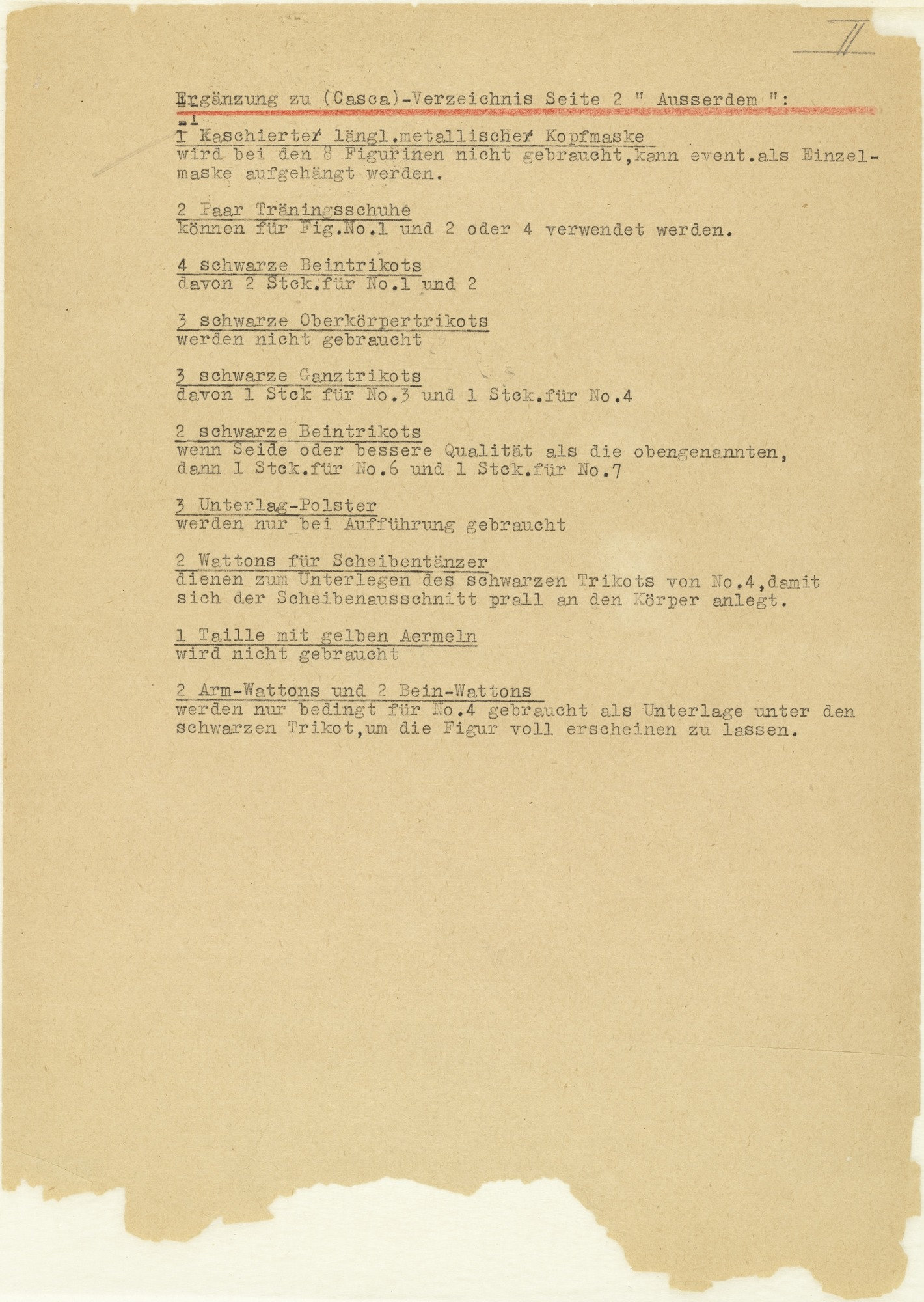

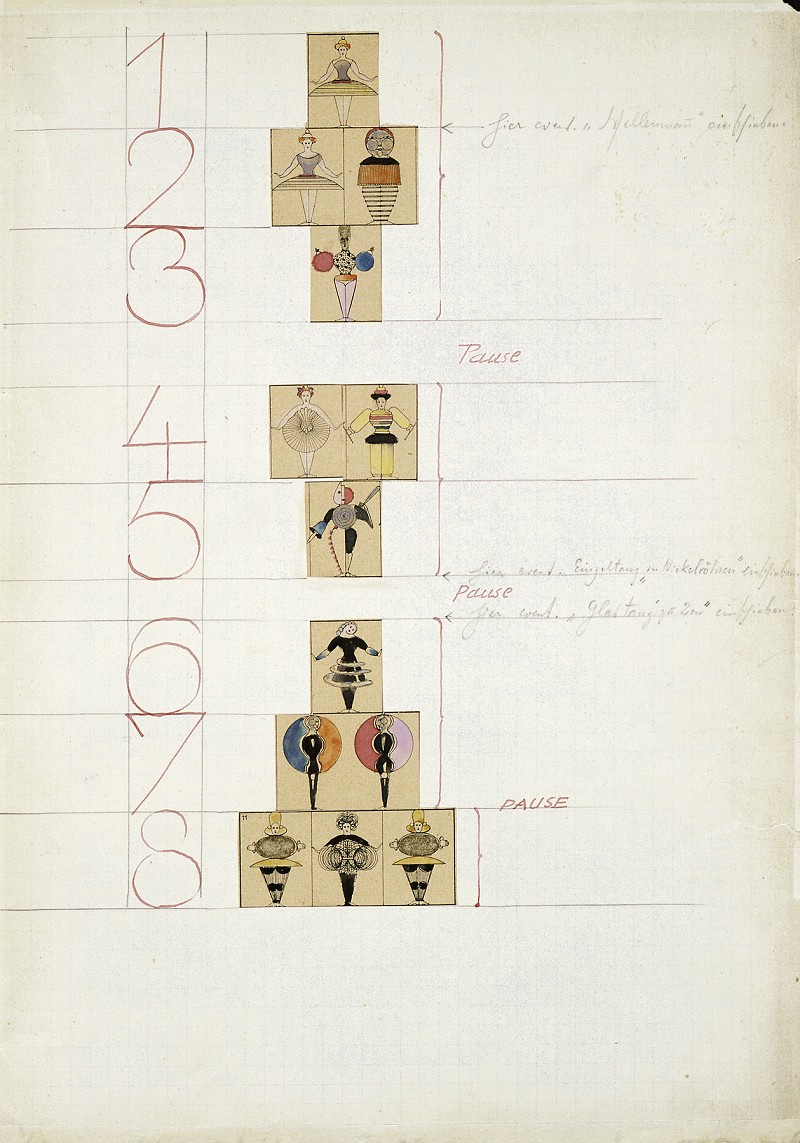

As you can see in the images further up, Schlemmer left few notes regarding the choreography, but he did sketch out the grouping and costuming of each of the three movements. (You can zoom in and get a closer look at the sketches above at the Bauhaus-archiv Museum.) As Anderson writes of the 1985 revived production, “unfortunately, Schlemmer’s choreography for these figures was forgotten long ago, and any new production must be based upon research and intuition.” The basic outlines are not difficult to recover. Inspired by Arnold Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire, Schlemmer began to see ballet and pantomime as free from the baggage of traditional theater and opera. Drawing from the stylizations of pantomime, puppetry, and Commedia dell’Arte, Schlemmer further abstracted the human form in discrete shapes—cylindrical necks, spherical heads, etc—to create what he called “figurines.” The costuming, in a sense, almost dictates the jerky, puppet-like movements of the dancers. (These three costumes below date from the 1970 recreation of the piece.)

Schlemmer’s radical production has somehow not achieved the level of recognition of other avant-garde ballets of the time, including Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire and Stravinsky’s, Nijinsky-choreographed The Rite of Spring. The Triadic Ballet, with music composed by Paul Hindemith, toured between 1922 and 1929, representing the ethos of the Bauhaus school, but at the end of that period, Schlemmer was forced to leave “an increasingly volatile Germany,” writes Frost. Revivals of the piece, such as a 1930 exhibition in Paris, tended to focus on the “figurines” rather than the dance. Schlemmer made many similar performance pieces in the 20s (such as a “mechanical cabaret”) that brought together industrial design, dance, and gesture. But perhaps his greatest legacy is the bizarre costumes, which were worn and copied at various Bauhaus costume parties and which went on to directly inspire the look of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and the glorious excesses of David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust stage show.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2016.

Related Content:

32,000+ Bauhaus Art Objects Made Available Online by Harvard Museum Website

Bauhaus Ballet: A Dance of Geometry

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness