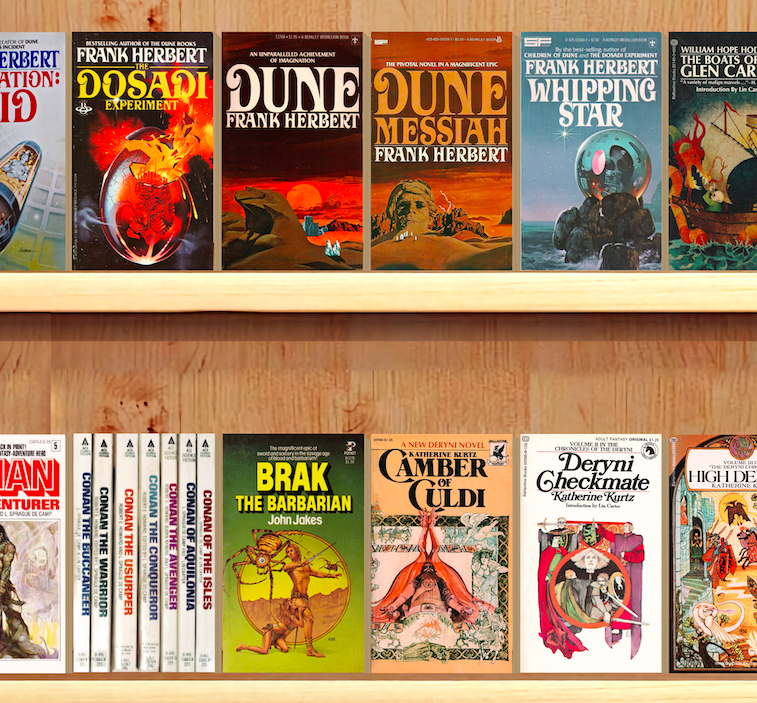

Dune: Part Two has been playing in theaters for less than a week, but that’s more than enough time for its viewers to joke about the aptness of its title. For while it comes, of course, as the second half of Denis Villeneuve’s adaptation of Frank Herbert’s influential sci-fi novel, it also contains a great many heaps of sand. Such visuals honor not just the story’s setting, but also the form of Herbert’s inspiration to write Dune and its sequels in the first place. The idea for the whole saga came about, he says in the 1969 interview above, because he’d wanted to write an article “about the control of sand dunes.”

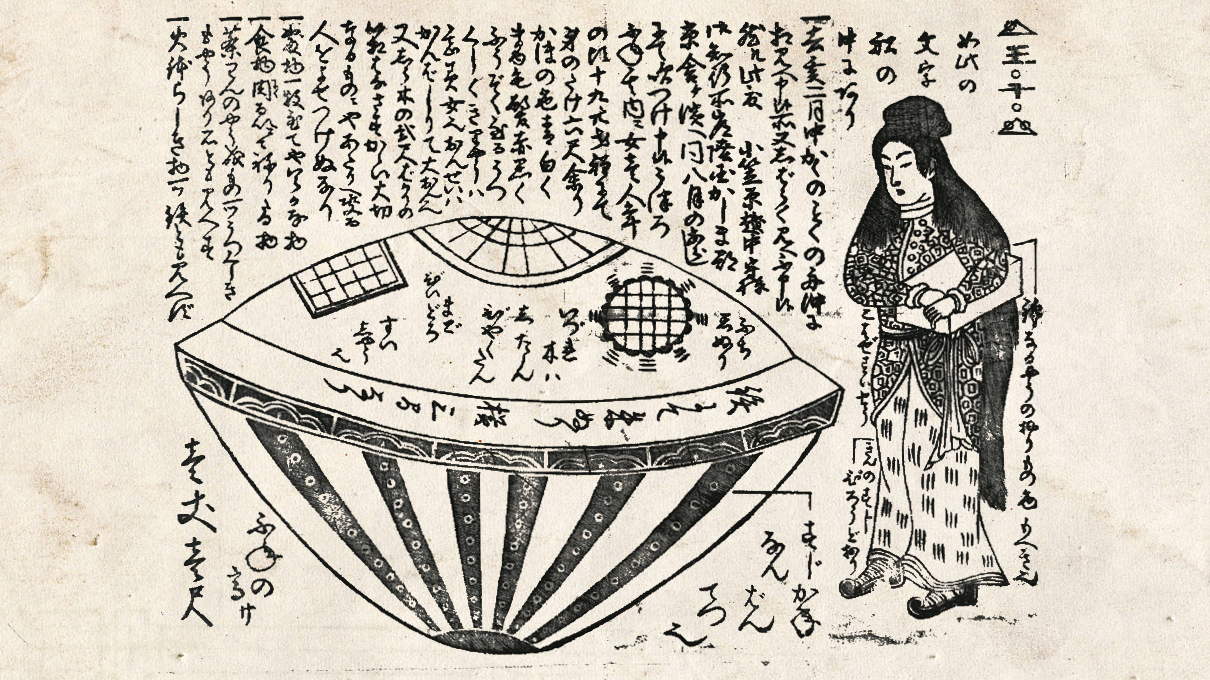

“I’m always fascinated by the idea of something that is either seen in miniature and that can be expanded to the macrocosm or which, but for the difference in time, in the flow rate, and the entropy rate, is similar to other features which we wouldn’t think were similar,” he goes on to explain. When viewed the right way, sand dunes turn out to behave “like waves in a large body of water; they just are slower. And the people treating them as fluid learn to control them.” After enough research on this subject, “I had something enormously interesting going for me about the ecology of deserts, and it was — for a science fiction writer, anyway — it was an easy step from that to think: What if I had an entire planet that was a desert?”

That may have turned out to be one of the defining ideas of Dune, but there are plenty of others in there with it. “We all know that many religions began in a desert atmosphere,” Herbert says, “so I decided to put the two together because I don’t think that any one story should have any one thread. I build on a layer technique, and of course putting in religion and religious ideas you can play one against the other.” And “of course, in studying sand dunes, you immediately get into not just the Arabian mystique but the Navajo mystique and the mystique of the Kalahari primitives and all.” From his technical curiosity about sand, the story’s host of ecological, religious, linguistic, political, and indeed civilizational themes emerged.

Conducted in Herbert’s Fairfax, California home in 1969 by literature professor and science-fiction enthusiast Willis E. McNelly (who would later compile The Dune Encyclopedia), the interview goes down a number of intellectual byways that will be fascinating to curious fans. In its eighty minutes, Herbert reflects on everything from corporations to hippies, the tarot to Zen, and Lawrence of Arabia to John F. Kennedy. The late president’s then-just-beginning sanctification in America gets him talking about one of Dune’s threads in particular, about the “way a messiah is created in our society.” The elevation of a messiah is an act of myth-making, after all, and “man must recognize the myth he is living in.”

Related content:

The Dune Franchise Tries Again — Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #110

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.