Note: With the passing of Jeff Beck, we’re bringing back a vintage post from our archive featuring the early years of the legendary guitarist. You can read his obituary here.

Art film and rock and roll have, since the 60s, been soulmates of a kind, with many an acclaimed director turning to musicians as actors, commissioning rock stars as soundtrack artists, and filming scenes with bands. Before Nicolas Roeg, Jim Jarmusch, David Lynch, Martin Scorsese and other rock-loving auteurs did all of the above, there was Michelangelo Antonioni, who barreled into the English-language market, under contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, with a trilogy of films steeped in the sights and sounds of sixties counterculture.

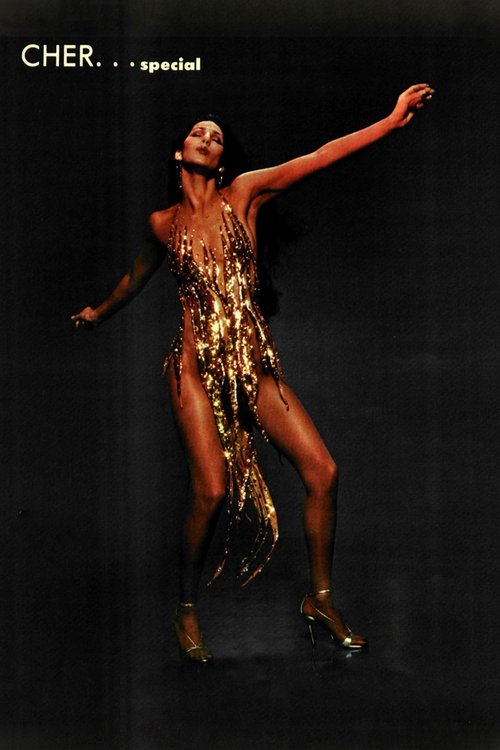

Blowup, the first and by far the best of these, though scored by jazz pianist Herbie Hancock, prominently featured the Yardbirds—with both Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck. In the memorable scene above, Beck smashes his guitar to bits after his amp goes on the fritz. The Italian director “envisioned a scene similar to that of Pete Townshend’s famous ritual of smashing his guitar on stage,” notes Guitarworld’s Jonathan Graham. “Antonioni had even asked The Who to appear in the film,” but they refused.

In stepped the Yardbirds, during a pivotal moment in their career. The year before, they released mega-hit “For Your Love,” and said goodbye to lead guitarist Eric Clapton. Beck, his replacement, heralded a much wilder, more experimental phase for the band. Jeff Beck, it seemed, could play anything, but what he didn’t do much of onstage is emote. Next to the guitar-smashing Townshend or the fire-setting Hendrix (see both below), he was a pretty reserved performer, though no less thrilling to watch for his virtuosity and style.

But as he tells it, Antonioni wouldn’t let the band do their “most exciting thing,” a cover of “Smokestack Lightning” that “had this incredible buildup in the middle which was just pow!” That moment would have been the natural pretext for a good guitar smashing.

Instead, the set piece with the broken amp gives the introverted Beck a reason to get agitated. As Graham describes it, he also played a guitar specially designated as a prop:

Due to issues over publishing, the Yardbirds classic “Train Kept A‑Rollin’,” was reworked as “Stroll On” for the performance, and as the scene involved the destruction of an instrument, Beck’s usual choice of his iconic Esquire or Les Paul was swapped for a cheap, hollow-body stand-in that he was directed to smash at the song’s conclusion.

The scene is more a tantrum than the orgiastic onstage freak-out Townshend would probably have delivered. Its chief virtue for Yardbird’s fans lies not in the funny, out-of-character moment (which SF Gate film critic Mick LaSalle calls “one of the weirdest scenes in the movie”). Rather, it was “the chance,” as one fan tells LaSalle, “in the days before MTV and YouTube, to see the Yardbirds, with Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page.” Antonioni had seized the moment. In addition to firing “the opening salvo of the emerging ‘film generation,’” as Roger Ebert wrote, he gave contemporary fans a reason (in addition to explicit sex and nudity), to go see Blowup again and again.

Related Content:

13-Year-Old Jimmy Page Plays Guitar on TV in 1957, an Early Moment in His Spectacular Career

Jim Jarmusch: The Art of the Music in His Films

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness